Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

13 citations

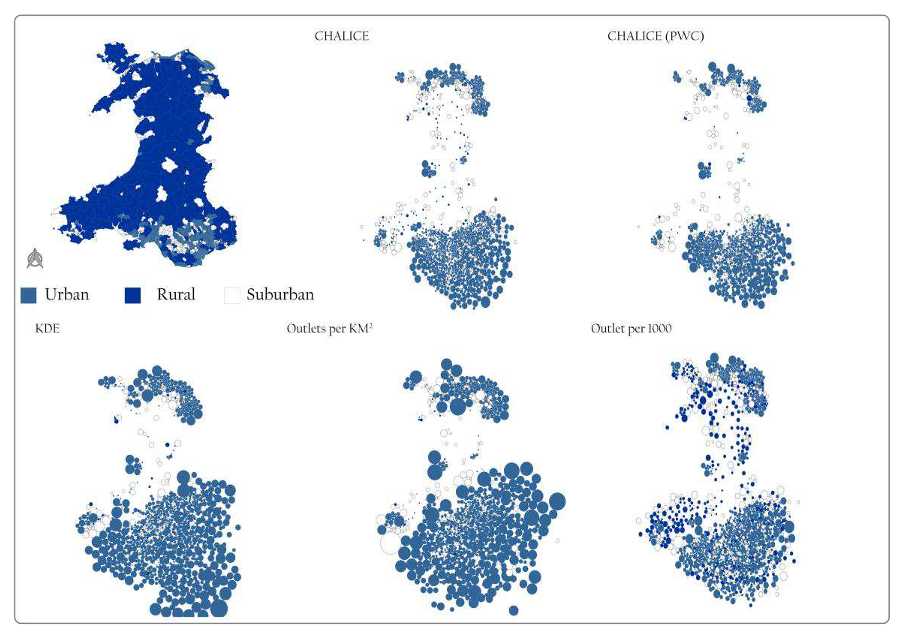

...We will adapt a previous methodology that modelled ‘change in alcohol outlet density and alcohol-related harm to population health’ (CHALICE).(60) The distance decay for this accessibility model will be updated to emulate how people engage with GBS as opposed to alcohol outlets....

[...]

9 citations

[...]

9 citations

4 citations

127 citations

...This has been widely reported as a definition of a localised neighbourhood and used extensively in previous research (e.g. Jiao et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2014)....

[...]

104 citations

...The Butterworth filter produces a small zone of zero impedance directly around the measurement point followed by a smooth decay so that zero weighting is realised at maximum threshold distance (Langford et al., 2012)....

[...]

...CHALICE method is not without limitations; the use of 10 minutes walking time to define a local neighbourhood is widely reported in the literature (Hewko et al., 2002; Langford et al., 2012; McGrail, 2012)....

[...]

...We rescaled the adjusted distances to give a value between 0 and 1 (1 high access, 0 poorer access) using a Butterworth filter gravity model (Langford et al., 2012), thus giving closer outlets a higher weighting than those further away from a residence....

[...]

...The CHALICE method is not without limitations; the use of 10 minutes walking time to define a local neighbourhood is widely reported in the literature (Hewko et al., 2002; Langford et al., 2012; McGrail, 2012)....

[...]

100 citations

...Research has shown that omission of network routes can result in falsely assigning places as accessible (Apparicio and Seguin 2006; Higgs et al., 2012; Mizen et al., 2015)....

[...]

...…of a geographic network in analyses is an important component of measuring access to goods, services and places of interest as demonstrated by Apparicio et al. (2008), Higgs et al. (2012) and Mizen et al. (2015), which non-network approaches often resulting in significant variations in findings....

[...]

97 citations

...It is underpinned by key theoretical principles of graph theory and topology (Curtin, 2007), population distribution modelling (Stewart and Warntz, 1958) and it informs spatial interaction modelling (Roy and Thill, 2003)....

[...]

96 citations

..., 2005) and (2) Kernel density estimate measures (KDE), which model distance decay within user-defined neighbourhoods (Berke et al., 2010; Major et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2015)....

[...]

...…measures are (1) counts per walking or driving neighbourhood (‘buffer zone’) (Huckle et al., 2008; Pollack et al., 2005) and (2) Kernel density estimate measures (KDE), which model distance decay within user-defined neighbourhoods (Berke et al., 2010; Major et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2015)....

[...]

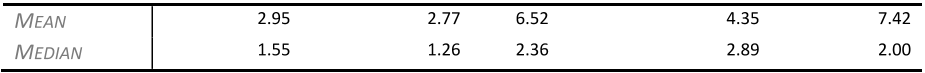

The interactions between multi-scale AOD and health and social outcomes are an important area for future work. For example, in one of the LSOAs with a zero value there are 16 outlets within the LSOA ( but beyond 10 minutes walk of the PWC ), and a further 6 outlets in an adjacent LSOA but close enough to the boundary to be accessible. However, the authors further demonstrate that this problem is exacerbated when the results are examined over a whole country with stratification by rural-urban classification revealing over and under inflation of AOD.