MNRAS 464, 1659–1675 (2017) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2437

Advance Access publication 2016 September 27

A chronicle of galaxy mass assembly in the EAGLE simulation

Yan Qu,

1‹

John C. Helly,

2

Richard G. Bower,

2

Tom Theuns,

2

Robert A. Crain,

3

Carlos S. Frenk,

2

Michelle Furlong,

2

Stuart McAlpine,

2

Matthieu Schaller,

2

Joop Schaye

4

and Simon D. M. White

5

1

National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20A Datun Road, Chaoyang, Beijing 10012, China

2

Institute of Computational Cosmology, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK

3

Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, 146 Brownlow Hill, Liverpool L3 5RF, UK

4

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Postbus 9513, NL-2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands

5

Max-Planck-Institut f

¨

ur Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strae 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany

Accepted 2016 September 26. Received 2016 August 29; in original form 2016 March 28

ABSTRACT

We analyse the mass assembly of central galaxies in the Evolution and Assembly of Galaxies

and their Environments (EAGLE) hydrodynamical simulations. We build merger trees to

connect galaxies to their progenitors at different redshifts and characterize their assembly

histories by focusing on the time when half of the galaxy stellar mass was assembled into the

main progenitor. We show that galaxies with stellar mass M

∗

< 10

10.5

M

⊙

assemble most of

their stellar mass through star formation in the main progenitor (‘in situ’ star formation). This

can be understood as a consequence of the steep rise in star formation efficiency with halo

mass for these galaxies. For more massive galaxies, however, an increasing fraction of their

stellar mass is formed outside the main progenitor and subsequently accreted. Consequently,

while for low-mass galaxies, the assembly time is close to the stellar formation time, the stars

in high-mass galaxies typically formed long before half of the present-day stellar mass was

assembled into a single object, giving rise to the observed antihierarchical downsizing trend.

In a typical present-day M

∗

≥ 10

11

M

⊙

galaxy, around 20 per cent of the stellar mass has an

external origin. This fraction decreases with increasing redshift. Bearing in mind that mergers

only make an important contribution to the stellar mass growth of massive galaxies, we find

that the dominant contribution comes from mergers with galaxies of mass greater than one-

tenth of the main progenitor’s mass. The galaxy merger fraction derived from our simulations

agrees with recent observational estimates.

Key words: galaxies: evolution – galaxies: formation – galaxies: high-redshift – galaxies:

interactions – galaxies: stellar content.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the cold dark matter (CDM) cosmological model, the growth

of dark matter haloes is largely self-similar, with larger haloes be-

ing formed more recently than their low-mass counterparts. The

formation and assembly of galaxies are, however, much more com-

plex. Feedback from massive stars and the formation of black holes

generates a strongly non-linear relationship between the masses of

dark matter haloes and those of the galaxies they host. For low-mass

haloes (with mass 10

11.5

M

⊙

), the stellar mass increases rapidly,

with a slope of ∼2, but in higher mass haloes, the stellar mass of

the main (or ‘central’) galaxy increases much more slowly than the

⋆

E-mail:

quyan@nao.cas.cn

halo mass, with a slope of ∼0.5 (e.g. Benson et al. 2003; Behroozi,

Wechsler & Conroy

2013; Moster, Naab & White 2013). The mass

assembly of galaxies will therefore be quite different from those of

their parent haloes. Establishing how galaxies assemble their stars

over cosmic time is then central to understanding galaxy formation

and evolution.

One question we need to answer is the relative importance of the

growth of galaxies via internal ongoing star formation (‘in situ’),

in comparison to the mass contributions of external processes (e.g.

Guo & White

2008; Zolotov et al. 2009;Oseretal.2010; Font et al.

2011; McCarthy et al. 2012; Pillepich, Madau & Mayer 2015).

These external processes can be further divided to distinguish be-

tween the mass growth due to mergers with galaxies of comparable

mass (‘major mergers’), and the mass gained from much smaller

galaxies (‘minor mergers’) or barely resolved systems and diffuse

C

2016 The Authors

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Astronomical Society

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/464/2/1659/2290988

by Leiden University user

on 11 January 2018

1660 Y. Qu et al.

mass (‘accretion’). While major mergers can rapidly increase a

galaxy’s stellar mass, minor mergers are much more common (e.g.

Hopkins et al.

2008; Parry, Eke & Frenk 2009).

To evaluate the relative importance of mergers to galaxy assem-

bly, we need to know their merging histories. From an observational

perspective, counts of close galaxy pairs (e.g. Williams, Quadri &

Franx

2011;Man,Zirm&Toft2014), or galaxies with disturbed

morphologies (e.g. Lotz et al.

2008; Conselice, Yang & Bluck 2009;

L

´

opez-Sanjuan et al.

2011; Stott et al. 2013), provide a census of

galaxy mergers. These values can be further converted into galaxy

merger rates t hrough the use of a merger time-scale (e.g. Kitzbichler

& White

2008). Unfortunately, those methods have their own lim-

itations: galaxies in close-pairs may not be physically related, and

may be chance line-of-sight superpositions; morphological distur-

bances are not unique to galaxy mergers. For example, clumpy star

formation driven by gravitational instability can also foster the for-

mation of galaxies with irregular morphologies (Lotz et al.

2008).

In addition, these methods are sensitive to the merger stage and

the mass ratio of the merging galaxies. Due to these limitations, the

scatter between merger rate measurements is large, and it is difficult

to make a reliable assessment of the complementary contribution

of mergers to galaxy growth. Recently, deep surveys have begun

to shed more light on the galaxy merger rate at high redshifts (e.g.

Man et al.

2014). Even so, the evolution of the merger rate remains

controversial. An alternative approach is to extract the merger rates

of galaxies from a model that reproduces the observed abundance

of galaxies (and their distribution in mass), and its evolution with

redshift, in a full cosmological context.

In the hierarchical structure formation scenario, the assembly of

galaxies is believed to be closely related to the formation histories

of their parent haloes. The practice of using halo merger histories

to understand the build-up of galaxies can be traced back to Bower

(

1991), Cole (1991), and Kauffmann, White & Guiderdoni (1993).

In these pioneering works, the growth of haloes is described by

analytical methods. Numerical techniques like N-body numerical

simulations can deal more accurately with the gravitational pro-

cesses underlying the evolution of cosmic structure. The clustering

of haloes is tracked, snapshot by snapshot, and stored in a tree

form (‘merger tree’). Halo merger trees therefore record, in a direct

way, when and how haloes assemble by accreting other building

blocks, and are widely used to rebuild galaxy assembly histories

(e.g. Kauffmann et al.

1993, 1999; Roukema et al. 1997; Springel

et al.

2001).

To compute galaxy merger rates, one possibility is to combine

the halo merger trees with a redshift-dependent abundance match-

ing model that statistically assigns galaxies to dark matter haloes

(Fakhouri & Ma

2008;Behroozietal.2013; Moster et al. 2013).

In this fashion, the observed abundance of galaxies can be inverted

to estimate the galaxy merger rate as a function of halo mass and

redshift. This provides a great deal of insight, but relies on the

accuracy of the statistical model. Although appealing because of

its close relation to the real data, the approach may miss physical

correlations between the merging objects. A preferable approach is

therefore to form galaxies within dark matter haloes using a physical

galaxy formation model. It is important to note, however, that reli-

able conclusions can only be obtained if the overall galaxy stellar

mass function accurately reproduces observational measurements

(Benson et al.

2003; Schaye et al. 2015).

One approach is to use ‘semi-analytic’ models of galaxy forma-

tion. By introducing phenomenological descriptions for feedback

from star formation and active galactic nuclei (AGN), such mod-

els are able to reproduce the observed galaxy stellar mass function

(e.g. Bower et al.

2006; Croton et al. 2006

, for a recent review, see

Knebe et al.

2015). De Lucia et al. (2006) study the assembly of

elliptical galaxies in a semi-analytic model based on the model of

Croton et al. (

2006). They find that stars in massive galaxies (with

stellar mass M

∗

≥ 10

11

M

⊙

) are formed earlier (z 2.5) but are as-

sembled later (by z ≈ 0.8). De Lucia & Blaizot (

2007) show further

that massive members in galaxy clusters assemble through mergers

late in the history of the Universe, with half of their present-day

mass being in place in their main progenitor by z ≈ 0.5. In contrast,

less massive galaxies undergo relatively few mergers, acquiring

only 20 per cent of their final stellar mass from external objects.

Parry et al. (

2009) study the assembly and morphology of galaxies

in the semi-analytic model of Bower et al. (

2006). They found many

similarities, but also important disagreements, stemming primarily

from the differing importance of disc instabilities in the two mod-

els. Parry et al. (

2009) find that major mergers are not the primary

mass contributors to most spheroids except the brightest ellipticals.

This, instead, is brought in by minor mergers and disc instabilities.

In their model, the majority of ellipticals, and the overwhelming

majority of spirals, never experience a major merger.

Semi-analytic studies such as those above give important insights

but suffer from the limitations inherent to the approach, for example,

the neglect of tidal stripping of infalling satellites and the absence of

information about the spatial distribution of stars, as well as being

limited by the overall accuracy of the model. Numerical simulations

have fewer limitations, and have thus become an alternative useful

tool for these studies. Hopkins et al. (

2010) compare the galaxy

merger rates derived from a variety of analytical models and hydro-

dynamical simulations. They find that the predicted galaxy merger

rates depend strongly on the prescriptions for baryonic physical pro-

cesses, especially those in satellite galaxies. For example, the lack

of strong feedback can result in a difference in predicted merger

rates by as much as a factor of 5. Mass ratios used in merger clas-

sification also have an impact on merger rate prediction. Using the

stellar mass ratio, rather than the halo mass ratio, can result in an

order of magnitude change in the derived merger rate.

With rapidly increasing computational power and much pro-

gresses in modelling physical processes on subgrid scales, cosmo-

logical N-body hydrodynamical simulations are increasingly capa-

ble of capturing the physics of galaxy formation (e.g. Hopkins et al.

2013; Vogelsberger et al. 2014). The Evolution and Assembly of

Galaxies and their Environments (EAGLE) simulation project ac-

curately reproduces the observed properties of galaxies, including

their stellar mass, sizes, and formation histories, within a large and

representative cosmological volume (Schaye et al.

2015; Furlong

et al.

2015a,b). This degree of fidelity makes the EAGLE simu-

lations a powerful tool for understanding and interpreting a wide

range of observational measurements. Previous papers have focused

on the evolution of the mass function and the size distribution of

galaxies (Furlong et al.

2015a,b), the luminosity function and colour

diagram (Trayford et al.

2015) and galaxy rotation curves (Schaller

et al.

2015a), as well as many aspects of the H

I and H

2

distribution

of galaxies (Lagos et al.

2015;Bah

´

eetal.2016; Crain et al. 2016)

in the EAGLE Universe. But none has tracked the assembly of in-

dividual galaxies and decipher the underlying mechanisms as yet.

As an attempt to shed some light on the issue, in this work, we

connect galaxies seen at different redshifts, creating a merger

tree that enables us to establish which high-redshift fragments col-

lapse to form which present-day galaxies (and vice versa). In this

way, we can quantify the importance of in situ star formation rel-

ative to the mass gain from galaxy mergers and diffuse accretion.

Throughout the paper, we will focus on the main, or ‘central’,

MNRAS 464, 1659–1675 (2017)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/464/2/1659/2290988

by Leiden University user

on 11 January 2018

Galaxy mass assembly in the EAGLE simulation 1661

galaxies, avoiding the complications of environmental processes

such as ram pressure stripping and strangulation that suppress star

formation and strip stellar mass from satellites. Unless otherwise

stated, stellar masses refer to the stellar mass of a galaxy at the

redshift of observation, not to the initial mass of stars formed.

The outline of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we provide

a brief overview of the numerical techniques and subgrid physi-

cal models employed by the EAGLE simulations, and describe the

methodology used to construct merger trees from simulation out-

puts. We investigate the assembly histories and merger histories of

galaxies and discuss the impact of feedback on galaxy mass build-

up in Section 3. We compare our results with some previous works

in Section 4, and finally summarize in Section 5. The appendices

present the detailed criteria we use to define galaxy mergers and

show the impacts of our choices of galaxy mass on our results. The

cosmological parameters used in this work is from the Planck mis-

sion (Planck Collaboration XVI

2014),

= 0.693,

m

= 0.307,

h = 0.677, n

s

= 0.96, and σ

8

= 0.829.

2 EAGLE SIMULATION AND MERGER TREE

2.1 EAGLE simulation

The galaxy samples for this study are selected from the EAGLE

simulation suite (Crain et al.

2015; Schaye et al. 2015). The

EAGLE simulations follow the evolution (and, where appropri-

ate, the formation) of dark matter, gas, stars, and black holes from

redshift z = 127 to the present day at z = 0. They were carried

out with a modified version of the

GADGET 3 code (Springel 2005)

using a pressure–entropy-based formulation of smoothed particle

hydrodynamics method (Hopkins

2013), coupled to several other

improvements to the hydrodynamic calculation (Dalla Vecchia., in

preparation; Schaye et al.

2015; Schaller et al. 2015b). The simula-

tions include subgrid descriptions for radiative cooling (Wiersma,

Schaye & Smith

2009), star formation (Schaye & Dalla Vecchia

2008), multi-element metal enrichment (Wiersma et al. 2009), black

hole formation (Rosas-Guevara et al.

2015; Springel, Di Matteo &

Hernquist

2005), as well as feedback from massive stars (Dalla

Vecchia & Schaye

2012) and AGN (for a complete description, see

Schaye et al.

2015). The subgrid models are calibrated using a well-

defined set of local observational constraints on the present-day

galaxy stellar mass function and galaxy sizes (Crain et al.

2015).

Each simulation outputs 29 snapshots to store particle properties

over the redshift range of 0 ≤ z ≤ 20. The corresponding time inter-

val between snapshot outputs ranges from ∼0.3 to ∼1.35 Gyr. The

largest EAGLE simulation, hereafter referred to as Ref-L100N1504,

employs 1504

3

dark matter particles and an initially equal number

of gas particles in a periodic cube with side-length 100 comoving

Mpc (cMpc) on each side. This setup results in a particle mass of

9.7 × 10

6

M

⊙

and 1.81 × 10

6

M

⊙

(initial mass) for dark matter and

gas particles, respectively. The gravitational force between particles

is calculated using a Plummer potential with a softening length set

to the smaller of 2.66 comoving kpc (ckpc) and 0.7 physical kpc

(pkpc).

The formation of galaxies involves physical processes operating

on a huge range of scales, from the gravitational forces that drive the

formation of large-scale structure on 10–100 Mpc scales, to the pro-

cesses that lead to the formation of individual stars and black holes

on 0.1 pc and smaller scales. Such a dynamic range, 10

9

in length

and perhaps 10

27

in mass, cannot be computed efficiently without

the use of subgrid models. Such models are inevitably approximate

and uncertain. In EAGLE, we require that the subgrid models are

physically plausible, numerically stable, and as simple as possible.

The uncertainty in these models introduces parameters whose val-

ues must be calibrated by comparison to observational data (Vernon,

Goldstein & Bower

2010). We explicitly recognize that these mod-

els are approximate and adopt the clear methodology for selecting

parameters and validating the model that is described in detail in

Schaye et al. (

2015) and Crain et al. (2015). The subgrid parame-

ters calibrated by requiring that the model fits three key properties

of local galaxies well: the galaxy stellar mass function, the galaxy

size – mass relation and the normalization of the black hole mass –

galaxy mass relation and that variations of the parameters alter the

simulation outcome in predictable ways (Crain et al.

2015). We find

that these data sets can be described well with physically plausible

values for the subgrid parameters. We then compare the s imulation

with further observational data to validate the simulation. We find

that it describes many aspects of the observed universe well (i.e.

within the plausible observational uncertainties), including the evo-

lution of the galaxy stellar mass function and star formation rates

(Furlong et al.

2015b), evolution of galaxy colours and luminosity

functions (Trayford et al.

2015). It also provides a good match to

observed O

VI column densities (Rahmati et al. 2016) and molecu-

lar content of galaxies (Lagos et al.

2015), as well as a reasonable

description of the X-ray luminosities of AGN (Rosas-Guevara et al.

2015). The good agreement with these diverse data sets, especially

those distantly related to the calibration data, provides good rea-

son to believe that the simulation provides a good description of

the evolution of galaxies in the observed Universe. It can therefore

be used to explore galaxy assembly histories in ways that are not

accessible to observational studies.

2.2 Halo identification and subhalo merger tree

Building subhalo merger trees from cosmological simulations in-

volves two steps: first, we identify haloes and subhaloes as gravi-

tationally self-bound structures; secondly, we identify the descen-

dants of each subhalo across snapshot outputs and establish the

descendant–progenitor relationship over time.

2.2.1 Halo identification

Dark matter structures in the EAGLE simulations are initially iden-

tified using the ‘Friends-of-Friends’ (FoF) algorithm with a linking

length of 0.2 times the mean inter-particle spacing (Davis et al.

1985). Other particles (gas, stars and black holes) are assigned to

the same FoF group as their nearest linked dark matter neighbours.

The gravitationally bound substructures within the FoF groups are

then identified by the SUBFIND algorithm (Springel et al.

2001;

Dolag et al.

2009). Unlike the FoF group finder, SUBFIND consid-

ers all species of particle and identifies self-bound subunits within

a bound structure which we refer to as ‘subhaloes’. Briefly, the

algorithm assigns a mass density at the position of every particle

through a kernel interpolation over a certain number of its nearest

neighbours. The local minima in the gravitational potential field

are the centres of subhalo candidates. The particle membership of

the subhaloes is determined by the iso-density contours defined

by the density saddle points. Particles are assigned to at most one

subhalo. The subhalo with a minimum value of the gravitational

potential within an FoF group is defined as the main subhalo of the

group. Any particle bound to the group but not assigned to any other

subhaloes within the group are assigned to the main subhalo.

MNRAS 464, 1659–1675 (2017)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/464/2/1659/2290988

by Leiden University user

on 11 January 2018

1662 Y. Qu et al.

2.2.2 Subhalo merger tree

Although they orbit within an FoF group, subhaloes survive as

distinct objects for an extended period of time. We therefore use

subhaloes as the base units of our merger trees: FoF group merger

trees can be rebuilt from subhalo merger trees if required. The first

and main step in building the merger tree is to link subhaloes across

snapshots. As in Springel et al. (

2005), we search the descendant

of a subhalo by tracing the most bound particles of the subhalo. We

use the D-Trees algorithm (Jiang et al.

2014) to locate the where-

abouts of the N

link

= min(N

linkmax

,max(f

trace

N, N

linkmin

)) most bound

particles of the subhalo, where N is the total particle number in the

subhalo. We use parameters N

linkmin

= 10, N

linkmax

= 100, f

trace

= 0.1

in the descendant search. The advantages of focusing on the N

link

most bound particles are two-fold. On the one hand, D-Trees can

identify a descendant even if most particles are stripped away leav-

ing only a dense core. On the other hand, the criterion minimises

misprediction of mergers during flyby encounters (Fakhouri & Ma

2008; Genel et al. 2009).

The descendant identification proceeds as follows. For a subhalo

A at a given snapshot, any subhalo at the subsequent snapshot that

receives at least one particle from A is labelled as a descendant

candidate. From those candidates, we pick the one that receives the

largest fraction of A’s N

link

most bound particles (denoted as B)as

the descendant of A. A is the progenitor of B.IfB receives a larger

fraction of its own N

link

most bound particles from A than from any

other subhalo at previous snapshot, A is the principal progenitor

of B. A descendant can have more than one progenitor, but only

one principal progenitor. The principal progenitor can be thought

of as ‘surviving’ the merger while the other progenitors lose their

individual identity.

Subhaloes sometimes exhibit unstable behaviour during merg-

ers, complicating the descendant/progenitor search. When a sub-

halo passes through the dense core of another subhalo, it may not

be identifiable as a separate object at the next snapshot, but will

then reappear in a later snapshot. From a single snapshot, there

is no way to know whether the subhalo has merged with another

subhalo, or has just disappeared temporarily, and we need to search

a few snapshots ahead in order to know which case it falls into.

In practice, we search up to N

step

= 5 consecutive snapshots ahead

for the missing descendants. This gives us between one and N

step

descendant candidates. If the subhalo is the principal progenitor of

one or more candidates, the earliest candidate that does not have a

principal progenitor is chosen to be the descendant. If there is no

such candidate, then the earliest one will be chosen. If the subhalo is

not the principal progenitor of any candidates, it will be considered

to have merged with another subhalo and no longer appears as an

identifiable object.

Occasionally, two subhaloes enter into a competition for bound

particles. This occurs as the participants orbit each other prior to

merging. In SUBFIND, the influence of a subhalo is based on its

gravitational potential well. When two subhaloes are close to each

other, their volumes of influence become intertwined and the def-

inition of the main halo may become unclear. For example, when

a satellite subhalo orbits closely to its primary host, the satellite

can be tidally compressed at some stage and become denser than

the host. At this point, the satellite may be classified as the central

object of the halo so that most of the halo particles are assigned

to it. At a later time, the original central, however, can surpass the

satellite in density and reclaim the halo particles. This contest can

last for several successive snapshots, accompanied by a see-saw

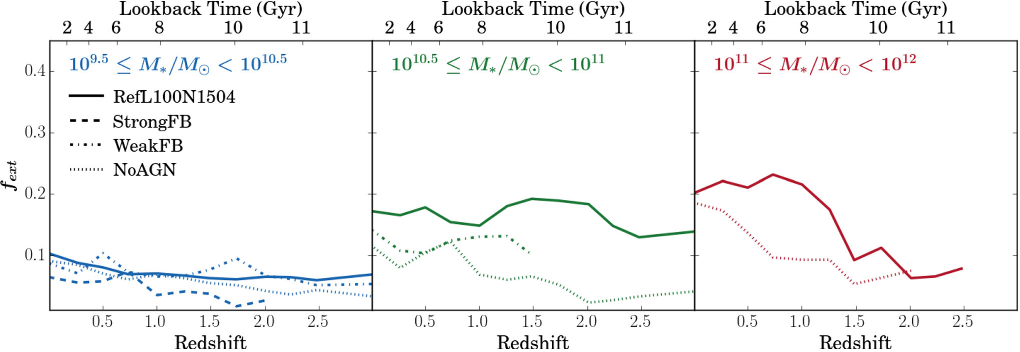

exchange of their physical properties during the merging. Fig.

1

Figure 1. A section of a subhalo merger tree illustrating how subhaloes

following branches A and B exchange particles before merging. The colour

of the solid symbol reflects the halo mass, while the size of the circle

represents the ‘branch mass’, which is the sum of the total mass of all the

progenitors sitting on the same branch. A see-saw behaviour is clearly seen

in the evolution of the halo mass, which may confuse identification of the

most important branch. Instead, we use branch mass to locate the main

branch of the tree. In this plot, branch A has the largest branch mass and

is therefore chosen as the main branch, even though its progenitors are not

always the most massive ones.

shows an example in which merging haloes take turns to be classi-

fied as the central host during the merging process. Overall, fewer

than 5 per cent of subhalo mergers in the EAGLE simulations ex-

hibit this behaviour, compatible with the statistics found by Wetzel,

Cohn & White (

2009). The fact that a fierce contest between sub-

haloes is sometimes seen during the merging process highlights the

inherent difficulties in appropriately describing subhalo properties

at that stage.

The property exchanges during such periods are not physical,

but rather stem from the requirement that particles be assigned to

a unique subhalo on the basis of the spatial coordinates and the

local density field in a single snapshot. The history of an object

is, however, conveniently simplified by modifying the definition

of the most massive progenitor to account for its mass in earlier

snapshots. We refer to this progenitor as the ‘main progenitor’, and

the branch they stay on in the object’s merger tree as the ‘main

branch’. Because of the mass exchange discussed above, we track

the main branch using the ‘branch mass’, the sum of the mass over all

particle species of all progenitors on the same branch ( De Lucia &

Blaizot

2007). The main progenitor is then the progenitor that has

the maximum branch mass among its contemporaries. This can

avoid the misidentification of main progenitors due to the property

exchanges occurring for merging subhaloes as we see in Fig.

1.

It is worth noting that according to this definition, a lower mass

progenitor which has existed for a long time can sometimes be

preferred over a more massive progenitor which has formed quickly,

when locating main progenitors.

The subhalo merger trees derived by the method described above

are publicly available through an

SQL data base

1

similar to that used

for the Millennium simulations (see McAlpine et al.

2016, for more

details).

1

http://www.eaglesim.org

MNRAS 464, 1659–1675 (2017)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/464/2/1659/2290988

by Leiden University user

on 11 January 2018

Galaxy mass assembly in the EAGLE simulation 1663

2.3 Galaxy sample, galaxy merger tree, and merger type

In this work, galaxies are identified as the stellar components of

the subhaloes. The main subhalo of a FoF halo hosts the ‘central’

galaxy, while other subhaloes within the group host satellite galax-

ies. We will focus on the central galaxies in our study, avoiding

the complications of environmental processes such as ram pressure

stripping and strangulation that suppress star formation and strip

stellar mass from satellite galaxies (e.g. Wetzel et al.

2013; McGee,

Bower & Balogh

2014;Barberetal.2016).

The stellar mass of a galaxy is measured using a spherical aper-

ture. This gives similar results to the commonly used 2D Petrosian

aperture used in observational work, but provides an orientation-

independent mass measurement for each galaxy. Previous studies

based on the EAGLE simulations adopt an aperture of 30 pkpc to

measure galaxy stellar mass (e.g. Furlong et al.

2015b; Schaye et al.

2015). Nevertheless, subhaloes do contain a significant population

of diffuse stars, particularly in more massive haloes (Furlong et al.

2015b). Such stars are probably deposited by interactions and tidal

stripping, and sometimes observed as low-surface brightness intr-

acluster/intragroup light (Theuns & Warren

1997; Zibetti & White

2004; McGee & Balogh 2010). Since the formation of massive

galaxies is a particular focus of this paper, we use a larger aperture,

with a radius of 100 pkpc, to calculate galaxy mass. Note that this

mass does not include the stellar mass of satellites lying within the

100 pkpc aperture. As we will show in Appendix C, this aperture

choice has little impact on galaxy properties for galaxies with stellar

mass M

∗

< 10

11

M

⊙

(see also Schaye et al. 2015).

Unless otherwise stated, the galaxy stellar mass in this work refers

to the actual mass of stars in the galaxy at the epoch of ‘observa-

tion’. Using actual mass replicates what an ideal observer would

measure and directly addresses the question of when the current

stellar population of the galaxy was formed/assembled. Neverthe-

less, we should note that the mass budget of the current stellar

population is a combination of two processes: stellar mass gain

via star formation, accretion and merging, and mass-loss through

stellar evolution processes. However, using the actual stellar mass

complicates interpretation of the relative mass contribution from

different types of merger events since it depends on the age of the

stellar population that is accreted. We therefore use the stellar mass

initially formed (‘initial mass’), not the actual stellar mass, to evalu-

ate the contributions from internal and external processes to galaxy

assembly. In practice, this distinction has little effect on the results

and we show the effect of using initial stellar mass throughout in

Appendix B.

2.3.1 Galaxy sample

Our study is based on the formation histories of 62 543 galax-

ies in the largest EAGLE simulation R ef-L100N1504, spanning

a stellar mass range of 10

9.5

–10

12

M

⊙

over redshift z = 0–3. In

order to test the robustness of our results to resolution, we also

extract 1381 galaxies within the same mass range, as a com-

parison sample, from the EAGLE simulation Recal-L025N0752

(2 × 752

3

dark matter and gas particles in a 25 cMpc box),

which has eight times better mass resolution and the same snap-

shot frequency as Ref-L100N1504. We use subgrid physical mod-

els with parameters recalibrated to the present-day observations,

as this provides the best match to the observed galaxy popula-

tion (see Schaye et al.

2015). In order to study the mass de-

pendence of galaxy assembly, we split our samples into three

stellar mass bins: a low-mass bin (10

9.5

≤ M

∗

< 10

10.5

M

⊙

), an

intermediate-mass bin (10

10.5

≤ M

∗

< 10

11

M

⊙

), and a high-mass

bin (10

11

≤ M

∗

< 10

12

M

⊙

).

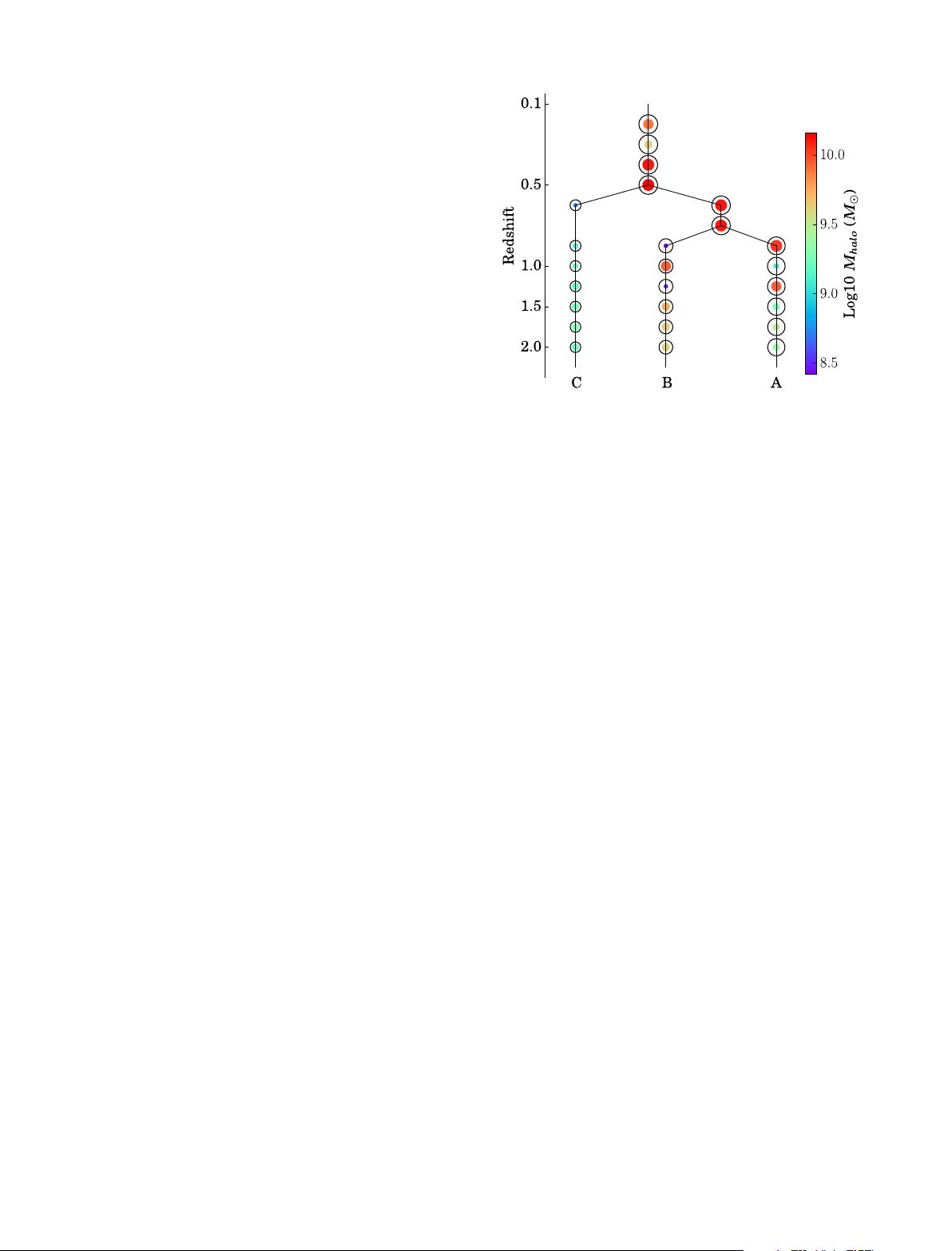

2.3.2 Galaxy merger tree

We construct galaxy merger trees by focusing on the stellar com-

ponent of the subhalo merger trees. Fig.

2 shows such a tree for a

galaxy with M

∗

= 1.7 × 10

11

M

⊙

at z = 0, together with images of

its star distribution highlighting its morphological evolution since

z = 1. The main branch of the tree is marked by the thick black

line. It is important to bear in mind that the identification of the

main branch is always based on t he branch mass; at any particular

epoch, the most massive galaxy progenitor may not lie on the main

branch. However, for the reasons described in Section 2.2.2, using

the branch mass yields more stable and intuitive results.

Galaxy merger trees appear broadly similar to subhalo merger

trees, except that the latter contain more fine branches corresponding

to small subhaloes within which no stars have formed. Galaxy trees

are also less affected by the mass exchange issue than subhalo trees,

as star particles are more spatially concentrated.

2.3.3 Merger type

The effects of tidal forces and torques during a merger depend on

the mass r atio of the merging systems (e.g. Barnes & Hernquist

1992). A merger between a low-mass satellite and a more massive

host is generally less violent than a merger between systems of

comparable mass, and has a less dramatic impact on the dynamics

and morphology of the host. It is therefore useful to classify mergers

into different t ypes according to the mass ratio between the two

merging systems, μ ≡ M

2

/M

1

(M

1

> M

2

). For galaxy mergers, μ

is the ratio of stellar masses between two merging galaxies. While

for halo mergers, it is the halo mass ratio.

While this is straightforward in semi-analytic models (since

galaxies are uniquely defined entities), in numerical simulations

(and in nature as well), merging systems experience mass-loss due

to tidal stripping throughout the merging process. Our strategy is

therefore to choose a separation criterion, R

merge

, and determine

the merger type when the merging systems are separated, for the

first time, by that distance or less. For galaxy mergers, we adopt

R

merge

= 5 × R

1/2

,whereR

1/2

is the half-stellar mass radius of the

primary galaxy (note that R

merge

is not a projected but a 3D separa-

tion). The value of R

merge

ranges from ∼20 to 200 pkpc in the stellar

mass range explored in this work (see Appendix A), and is s imilar

to the projected separation criteria adopted in observational galaxy

pair studies. For subhalo mergers, R

merge

= r

200

,wherer

200

is the

radius of a region around the FoF group of the subhaloes within

which the density is 200 times the cosmological critical density. In

the rare event that an object is located within the R

merge

of more than

one other object, i t is considered to be the merging companion of

the nearest one.

More often than not, the secondary object may have suffered

tidal stripping of mass when the merger type is determined due to

the finite time sampling of our snapshot outputs. To alleviate the

resulting misestimate of the mass ratio, we compare the mass of

the merging systems at the start of the merging event with that at

the previous snapshot, and use the maximum to calculate the mass

ratio μ. In our study, merging events are classified as major mergers

if μ ≥ 1/4; as minor mergers if 1/4 >μ≥ 1/10; and as diffuse

accretion, when μ<1/10. Our major merger definition is different

from that of C ole et al. (

2000) or De L ucia & Blaizot (2007)who

adopt a larger mass ratio ≥1/3, but is similar to more recent studies

MNRAS 464, 1659–1675 (2017)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/464/2/1659/2290988

by Leiden University user

on 11 January 2018