Ivanyna, Maksym; von Haldenwang, Christian

Working Paper

A comparative view on the tax performance of

developing countries: Regional patterns, non-tax

revenue and governance

Economics Discussion Papers, No. 2012-10

Provided in Cooperation with:

Kiel Institute for the World Economy – Leibniz Center for Research on Global Economic

Challenges

Suggested Citation: Ivanyna, Maksym; von Haldenwang, Christian (2012) : A comparative

view on the tax performance of developing countries: Regional patterns, non-tax revenue and

governance, Economics Discussion Papers, No. 2012-10, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

(IfW), Kiel

This Version is available at:

http://hdl.handle.net/10419/55262

Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen:

Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen

Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden.

Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle

Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich

machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen.

Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen

(insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten,

gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort

genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.

Terms of use:

Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your

personal and scholarly purposes.

You are not to copy documents for public or commercial

purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them

publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise

use the documents in public.

If the documents have been made available under an Open

Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you

may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated

licence.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/deed.en

A Comparative View on the Tax Performance of

Developing Countries: Regional Patterns,

Non-tax Revenue and Governance

Christian von Haldenwang

Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, DIE, Bonn

Maksym Ivanyna

Michigan State University

Abstract Some countries fail to ensure that their citizens and businesses make an

appropriate contribution to the financing of public tasks. But not all countries with a

low tax ratio automatically fall into this cat-egory. This paper presents an approach to

bridge the gap between probabilistic statements based on statistical analyses, and

country-specific information. Rather than defining general across-the-board criteria,

the approach accounts for different development levels and other influencing factors,

such as regional patterns, non-tax revenue and governance. Findings on individual

countries or groups of countries should put governments, donors and international

organisations in a better position to decide on tax reform programmes and aid

modalities.

JEL H20, H60, H27, H28

Keywords Tax system; tax ratio; governance; developing countries

Correspondence Christian.vonHaldenwang@die-gdi.de; ivanynam@msu.edu

© Author(s) 2012. Licensed under a Creative Commons License - Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Germany

Discussion Paper

No. 2012-10 | January 26, 2012 | http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2012-10

2

1. Introduction

Countries with a low tax yield or lax enforcement of tax laws are running out of time. Such interna-

tional players as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World

Bank and the G20 are calling for more determined action to combat tax evasion and avoidance. With

the world still fighting the effects of the global financial and economic crisis, there is growing pres-

sure on tax havens to increase the transparency of their tax systems and put an end to unfair com-

petitive practices. Developing countries, too, are being urged to do more to mobilize domestic re-

sources rather than rely on a constant inflow of official development assistance (ODA) funds (OECD

2010; European Commission 2010).

Some countries clearly fail to ensure that their citizens and businesses make an appropriate contribu-

tion to the financing of public tasks. In such cases there are a number of reasons for changing the

development portfolio, reducing ODA or even stopping cooperation altogether. But not all countries

with a low tax ratio automatically fall into this category. Governments, donors and international or-

ganizations need to be able to assess the performance of tax systems in a broader context of devel-

opment, governance and international cooperation.

The most important providers of this kind of information are the World Bank’s Country Policy and

Institutional Assessments (CPIAs) and Doing Business Reports, the OECD reports and databases, es-

pecially on sub-Saharan Africa, the European Commission’s Fiscal Blueprints, the Public Expenditure

and Financial Accountability (PEFA) Reports and the Collecting Taxes database funded by USAID.

Most developing countries are the subject of at least some country-specific information on tax sys-

tems and revenues.

However, much of the available in-depth information is not truly comparative,

1

The present paper combines quantitative and qualitative approaches to the comparative analysis of

tax systems. As a first step it argues that ‘tax performance’ should not be assessed against some ab-

solute values (such as the average OECD tax ratio) or theoretical tax yields. Rather, it should be ap-

proached as a function of tax ratio and development level (proxied as logged GDP per capita). The

relation between both variables is well-established both in theoretical and empirical terms (Mu-

sgrave 1969; Chelliah 1971; Tanzi 1992; Piancastelli 2001; Gambaro et al. 2007), which is why it is

used here to determine three broad groups of tax performers (‘low’, ‘average’ and ‘high’). In subse-

quent steps of the analysis, additional variables such as regional patterns, non-tax revenue and go-

vernance levels are introduced and discussed within a qualitative analytical framework, and with a

specific focus on the group of ‘low’ tax performers.

and much of the

comparative information is not truly in-depth. As a result, governments and donors usually approach

the issue of tax reform in developing countries on a strict case-by-case basis. Tax-related criteria of

donor programs or new aid modalities are defined without the potential of available comparative

data being fully tapped. The tax ratio (tax revenue as a percentage of GDP) in developing countries is

often assessed by comparing it to certain absolute threshold values, regional averages or OECD tax

ratios. None of these procedures, however, appears to be convincing, as they do not take any ac-

count at all of the conditions and development levels of individual countries.

Section 2 introduces the analytical narrative and discusses the problem of data quality and accessibil-

ity. Section 3 presents the main findings of the analysis. Section 4 summarizes the results and ad-

dresses the question of how development cooperation partners should handle the findings.

1

It could be argued that PEFA and CPIA scores do lend themselves to (within-country or cross-country)

comparisons. De Renzio (2009) and PEFA Secretariat (2009) discuss this issue with regard to PEFA scores.

3

2. Assessing tax performance – concepts, literature and data

State capacity includes the capacity to collect taxes. States with low per capita income do not, as a

rule, meet the administrative and institutional requirements for a tax system at OECD level. Public

expenditure, on the other hand, rises with higher development levels, generating pressure to mobil-

ize revenue (Wagner’s Law, see Musgrave 1969; de Ferranti et al. 2004). An appropriate appraisal of

a state’s efforts to tax its citizens must therefore take its level of development into account.

Hence, the first assumption made in this paper is that the capacity of a government to raise tax rev-

enue increases with that country’s development level. This assumption does not establish a causal

relationship between tax ratio and development level. We do not think that rich countries raise more

taxes simply because they are rich.

2

“Per capita income indicates the availability of resources to be taxed, as well as the existence

of administrative capabilities for collecting taxes: at higher levels of per capita income, econ-

omies tend to be more monetized and less informal, making it easier for the government to

collect taxes”.

Rather, we suspect that a number of underlying causalities oper-

ate in this relation, some of which are mentioned, for instance, by Cheibub (1998: 358-359):

Against this background, there is little sense in assessing a low-income country’s tax effort by com-

paring it to OECD levels or to certain absolute values – a reference we find astonishingly often in

development policy literature (see for instance UNDP 2010). Linking tax revenue to development

levels leads also to more realistic expectations concerning changes in tax revenue. Drastic alterations

from one year to another are typically the outcome of external shocks, or the product of data corrup-

tion and misreporting.

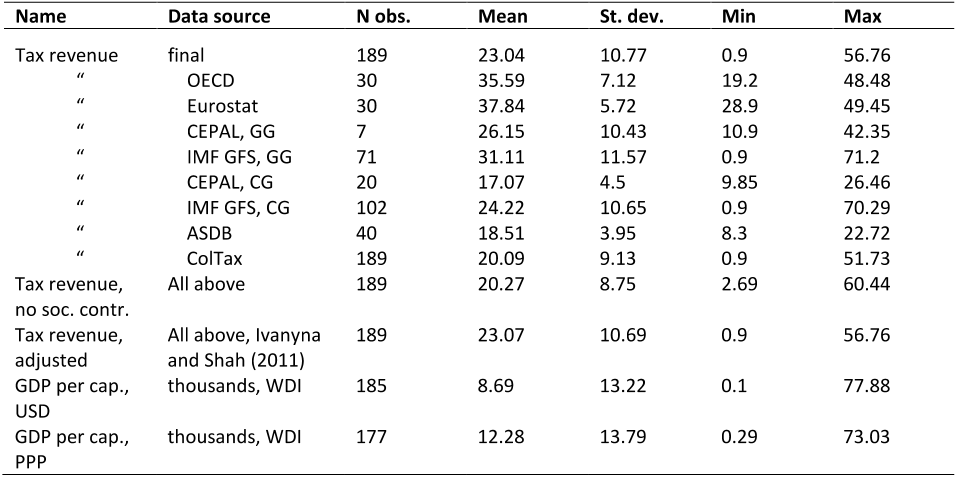

The paper relates the tax ratios of 177 countries to their logged GDP per capita. By means of an OLS

regression it establishes a trend line (fitted values) and determines the distance of each country from

this line. According to their position relative to the trend line, countries are then grouped into three

categories: average, high and low tax performers. Grouping countries into these broad categories

gives us a first idea of how they fare in terms of tax collection at a given point in time. By choosing

2007/08 as the most recent observation period, we cover the years before the outbreak of the world

economic crisis, with its rather distorting impacts on the public finances of many developing and

developed countries. We are also able to gather data for a large group of countries.

3

Besides gaining an impression of recent tax performance, we want to know how tax performance

changes over time. For instance, it could be that a country is still below the trend line, although it has

increased its tax ratio in recent years. Only long-term observation will provide information on the

fiscal development of a country or group of countries. We build two additional series for the periods

1997-99 and 2001-03 (roughly ten and five years from 2007/08). As governments, donors and inter-

national institutions are likely to be especially interested in countries with a persistently low, or even

diminishing, tax performance, we take a closer look at this group in our analysis.

The second assumption discussed in this paper relates to regional patterns of tax performance. Even

though every country has a tax system which reflects its specific political, social and economic condi-

2

Cheibub (1998) as well as Pessino and Fenochietto (2010) present evidence on the significance of GDP per

capita even accounting for other factors such as trade openness, agricultural production, foreign debt or

political variables. Several other studies show, however, that the variable tends to lose statistical signific-

ance or even changes signs once additional control variables are introduced. For instance, see Tanzi (1992);

Burgess and Stern (1993); Piancastelli (2001); Teera and Hudson (2004) (all controlling for country income

groups); Clist and Morrissey (2011) (distinguishing income groups and time periods); Mkandawire (2010)

(controlling for historical world market integration based on labour or cash crops).

3

For each of the countries of our sample, data from 2007 and 2008 were averaged and then compiled into

one series. For 14 countries (Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Cameroon, Dominica, Eritrea, Ga-

bon, Qatar, Oman, São Tome and Principe, Sudan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, West Bank and Gaza),

one of the two observations was missing. In these cases we took the remaining one.

4

tions, we would expect some regional factors to exert a measurable influence on the tax perfor-

mance of individual countries. To give an example, neighbouring countries may compete for private

sector investments, forcing them to take the tax levels (on corporate income, trade, etc.) of their

competitors into account. Political and cultural exchange or shared religious beliefs may contribute

to regionally similar views on the state, its relations to society and the functions it should perform. A

common colonial heritage (such as in Latin America or in parts of sub-Saharan Africa) could also lead

to a certain assimilation of taxation patterns – even more so if it is connected to specific economic

structures and patterns of world market integration (Mkandawire 2010).

Few studies have explored regional patterns of tax performance. Profeta et al. (2011) examine the

relation between political variables and tax revenue, focussing on three areas: Asia, Latin America

and new EU-members. Using pooled OLS-regressions with reginal dummies they find that “in some

cases the relationship between the tax structure and political variables appears to be region-specific”

(ibid., 4). Other authors (for instance Jiménez et al. 2010; di John 2008; Burgess and Stern 1993) ac-

count for regions in some parts of their analysis, but do not approach the subject in a systematic

manner.

The third assumption guiding our analysis concerns the relationship between tax and non-tax reve-

nue. Most approaches to the subject assume that governments with ‘easy’ access to alternative

sources of finance do not have a strong incentive to engage in cumbersome domestic tax collection.

On the one hand, exporters of non-renewable energy sources (oil, gas) and minerals (copper, gold)

may not have to achieve high tax ratios in order to finance public services. A state that receives sub-

stantial rents from oil or gas exports will feel little inclination to resort to the laborious business of

depriving its citizens of some of their income when it can finance its essential functions as things are.

The best example of this is the Persian Gulf states, some of which maintain single-digit tax ratios

despite having medium to high per capita incomes.

On the other hand, states heavily dependent on ODA grants may be tempted to refrain from addi-

tional domestic revenue mobilization – unless ODA conditions (such as co-financing schemes or tax

collection targets) change the incentive structure, or longer-term political perspectives lead govern-

ments actively to seek independence from ODA inflows. There is a growing body of research on these

issues (Bräutigam and Knack 2004; Knack 2008; Carter 2010; Gupta et al. 2003; Gambaro et al. 2007;

Benedek et al. 2011; Clist and Morrissey 2011), but findings are still inconclusive.

The fourth assumption concerns the governance dimension of revenue mobilization. A low tax yield

is not always the outcome of some kind of error or defective governance. Different societies have

different views on what states should do and how much they should cost. Of the OECD member

countries, the USA and Japan stand out as having a rather low tax yield, whereas the Nordic countries

are famous for their high tax ratio. Neither does our trend line necessarily represent the ‘golden

middle’ between under- and overtaxation, nor does every society aspire to become another Sweden

or Denmark.

Consequently, we should distinguish between states that collect few taxes because citizens want

them to have a low tax ratio and those where other aspects may be more important than the politi-

cal will of the citizens. Factors such as democratic participation, free and fair elections and regime

stability determine the capacity of societies to reach political decisions based on the common inter-

est, while such factors as administrative capacity, level of corruption and rule of law determine the

capacity of public administrations to implement these policies.

Societies with low levels of governance are typically not in a position to choose and implement a tax

system from a common interest perspective. Hence, in cases where low tax performance coincides

with low levels of governance we find it hard to believe that the tax ratio is the product of transpa-

rent, democratic decision-making and capable public administration. Rather, we would assume that

in these cases some powerful groups are imposing a tax system according to their particular interests

– or that they are successfully obstructing tax reform initiatives. In addition, we consider it easier in