A comparison of different nonparametric methods for inference on

additive models

Holger Dette

Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum

Fakult¨at f¨ur Mathematik

D - 44780 Bochum, Germany

Carsten von Lieres und Wilkau

Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum

Fakult¨at f¨ur Mathematik

D - 44780 Bochum, Germany

Stefan Sperlich

Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

Departamento de Estad´ıstica y Econometr´ıa

E - 28903 Getafe, Spain

May 10, 2001

Abstract

In this article we highlight the main differences of available methods for the analysis of regression

functions that are probably additive separable. We first discuss definition and interpretation of the

most common estimators in practice. This is done by explaining the different ideas of modeling

behind each estimator as well as what the procedures are doing to the data. Computational

aspects are mentioned explicitly. The illustrated discussion concludes with a simulation study on

the mean squared error for different marginal integration approaches. Next, various test statistics

for checking additive separability are introduced and accomplished with asymptotic theory. Based

on the asymptotic results under hypothesis as well as under the alternative of non additivity we

compare the tests in a brief discussion. For the various statistics, different smoothing and bootstrap

methods we perform a detailed simulation study. A main focus in the reported results is directed on

the (non-) reliability of the methods when the covariates are strongly correlated among themselves.

Again, a further point are the computational aspects. We found that the most striking differences

lie in the different pre-smoothers that are used, but less in the different constructions of test

statistics. Moreover, although some of the observed differences are strong, they surprisingly can

not be revealed by asymptotic theory.

1

AMS Subject Classification: 62G07, 62G10

Keywords: marginal integration, additive models, test of additivity.

1

Acknowledgements: This research was financially supported by the Spanish “Direcci´on General de Ense˜nanza Supe-

rior” (DGES), reference number PB98-0025 and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 475: Komplexit¨atsreduktion

in multivariaten Datenstrukturen, Teilprojekt A2; Sachbeihilfe: Validierung von Hypothesen, De 502/9-1). Parts of

this paper were written while the first author was visiting Perdue University and this author would like to thank the

Department of Statistics for its hospitality.

1

1 Introduction

In the last ten years additive models have attracted an increasing amount of interest in nonparametric

statistics. Also in the econometric literature these methods have a long history and are widely used

today in both, theoretical considerations and empirical research. Deaton and M¨ullbauer (1980) pro-

vided many examples in microeconomics where the additive structure follows from economic theory

of separable decision making like two step budgeting or optimization. Furthermore, additivity is the

natural structure when production processes have independent substitution rates for separable goods.

In statistics, additivity leads to the circumvention of the curse of dimensionality (see Stone 1985) that

usually affects multidimensional nonparametric regression.

The most common and best known nonparametric estimation approaches in these models can be

divided into three main groups: the backfitting (see Buja, Hastie and Tibshirani 1989, or Hastie and

Tibshirani 1990 for algorithms, and Opsomer and Ruppert 1997 or Mammen, Linton and Nielsen 1999),

series estimators (see Andrews and Whang 1990 or Li 2000), and the marginal integration estimator

(see Tjøstheim and Auestad 1994, Linton and Nielsen 1995, and also Kim, Linton, Hengartner 2000

for an important modification). Certainly, here we have mentioned only the main references respective

basic ideas and theory. Among them, to our knowledge, the series estimator is so far not explored in

practice, i.e. although straightforward implementation and good performance is declared, we could not

find a simulation study or an application of this method. Moreover, usually hardly feasible assumptions

are made on the series and its “smoothing parameters”, e.g. reducing bias and variance simultaneously,

but without giving a correct idea how to choose them in practice. The backfitting of Buja, Hastie and

Tibshirani (1989) is maybe the most studied additive model estimator in practice, and algorithms are

developed for various regression problems. However, the backfitting version of Mammen, Linton and

Nielsen (1999), for which closed theory is provided but no Monte-Carlo studies, differs a lot in definition

and implementation from that one. The marginal integration, finally, has experienced most extensions

in theory but actually a quite different interpretation than the aforementioned estimators. This was

first theoretically highlighted by Nielsen and Linton (1997) and empirically investigated by Sperlich,

Linton and H¨ardle (1999) in a detailed simulation study. The main point is that backfitting, at least the

version of Mammen et al. (1999), and series estimators are orthogonal projections of the regression

into the additive space whereas the marginal integration estimator always estimates the marginal

impact of the explanatory variables taking into account possible correlation among them. This led

Pinske (2000) to the interpretation of the marginal integration estimator as a consistent estimator of

weak separable components, which, in the case of additivity, coincide with the additive components.

From this it can be expected that the distance between the real regression function and its estimate

increases especially fast when the data generating regression function is not additive but estimated by

the sum of component estimates obtained from marginal integration instead of backfitting or series

estimates. A consequence could be to prefer marginal integration for the construction of additivity

tests. Nevertheless, until now backfitting was not used for testing simply because of the lack of theory

for the estimator.

Due to the mentioned econometric results and statistical advantages there is an increasing interest in

testing the additive structure. Eubank, Hart, Simpson and Stefanski (1995) constructed such a test but

used special series estimates that apply only on data observed on a grid. Gozalo and Linton (2000) as

well as Sperlich, Tjøstheim and Yang (2000) introduced a bootstrap based additivity test applying the

marginal integration. Here, Sperlich et al. (2000) concentrated on the analysis of particular interaction

terms rather than on general separability. Finally, Dette and von Lieres (2000) have summarized the

2

test statistics considered by Gozalo and Linton (2000) and compared them theoretically and also in a

small simulation study. Their motivation for using the marginal integration was its direct definition

which allows an asymptotic treatment of the test statistics using central limit theorems for degenerate

U-statistics. They argued that such an approach based on backfitting seems to be intractable, because

their asymptotic analysis does not require the asymptotic properties of the estimators as e.g. derived

by Mammen, Linton and Nielson (1999) but an explicit representation of the residuals. Further, Dette

and Munk (1998) pointed out several drawbacks in the application of Fourier series estimation for

checking model assumptions. For these and the former mentioned reasons we do not consider series

estimators for the construction of tests for additivity in this paper.

For the empirical researcher it would be of essential interest how the different methods perform in

finite samples and which method should be preferred. Therefore the present article is mainly concerned

about the practical performance of the different procedures and for a better understanding of some of

the above mentioned problems in estimating and testing. Hereby, the main part studies performance,

feasibility and technical differences of estimation respectively testing procedures based on different

estimators. We concentrate especially on the differences caused by the use of different (pre-)smoothers

in marginal integration, in particular on the classic approach of Linton and Nielsen (1995) and on the

internalized Nadaraya–Watson estimator (Jones, Davies and Park 1994) as suggested by Kim, Linton

and Hengartner (2000). Notice that this study is not thought as an illustration of the general statement

of consistency and convergence. Our main interest is directed to the investigation and comparison of

finite sample behavior of these procedures.

The marginal integration estimator becomes inefficient with increasing correlation in the regressors,

see Linton (1997). He suggested to combine the marginal integration with a one step backfitting

afterwards to reach efficiency. Unfortunately, this combination destroys any interpretability of the

estimate when the additivity assumption is violated. The same loss of efficiency was also observed

in a simulation study by Sperlich, Linton and H¨ardle (1999) for the backfitting estimator, although

these results do not reflect the asymptotic theory. In their article it is further demonstrated that with

increasing dimension the additive components are still estimated with a reasonable precision, whereas

the estimation of the regression function becomes problematic. This fact could cause problems for

prediction and for bootstrap tests. We will investigate and explain that the use of the internalized

Nadaraya–Watson estimator for the marginal integration can partly ameliorate this problem. This is

actually not based on theoretical results but more on numerical circumstances respective the handling

of “poor data areas”. Throughout this paper we will call the classical marginal integration estimator

CMIE, and IMIE the one using the internalized Nadaraya–Watson estimator as multidimensional

pre-smoother.

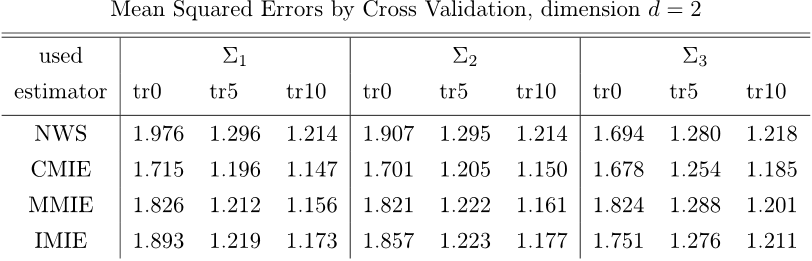

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we give the definitions of the analyzed

estimators and some more discussion about their advantages and disadvantages. Finally we provide

some simulation results on the Cross-Validation mean squared errors for the different methods of

estimation. In Section 3 we introduce various test statistics based in the IMIE to check the additivity

assumption, present closed form asymptotic theory and a theoretical comparison. Notice that for

the IMIE, at least for testing, little theory has been done until now and hardly empirical studies.

Therefore we provide both in this work, an extensive simulation study but also a closed theory about

the asymptotic properties for any new estimator and test we are considering. Section 4 finally is

dedicated to an intensive simulation study for these test statistics, all using bootstrap methods. The

proofs of the asymptotic results are cumbersome and deferred to the Appendix in Section 5.

3

2 Marginal Integration and Additive Models

Let us consider the general regression model

Y = m(X)+σ(X)ε (2.1)

where X =(X

1

,...,X

d

)

T

is a d-dimensional random variable with density f, Y is the real valued

response, and ε the error, independent of X with mean 0 and variance 1. Further, m, σ are unknown

(smooth) functions and the regression function m(·) has to be estimated nonparametrically. As in-

dicated above the marginal integration estimator is constructed to catch the marginal impact of one

or some regressors X

α

∈ IR

d

α

, d

α

<d. For the ease of notation we will restrict ourselves to the case

d

α

=1forallα. Notice first that in case of additivity, i.e. there exist functions m

α

, m

−α

such that

m(X)=m

α

(X

α

)+m

−α

(X

−α

) (2.2)

with X

−α

being the vector X without the component X

α

, the marginal impact of X

α

corresponds

exactly to the additive component m

α

. For identification we set E[m

α

(X

α

)] = 0 and consequently

E[Y ]=E[m

−α

(X

−α

)] = c. The marginal integration estimator is defined noting that

E

X

−α

[m(x

α

,X

−α

)] =

m(x

α

,x

−α

)f

−α

(x

−α

)dx

−α

(2.3)

= E

X

−α

[m

−α

(X

−α

)+m

α

(x

α

)] = c + m

α

(x

α

), (2.4)

where f

−α

denotes the marginal density of X

−α

, and the second line follows from the first line in the

case of additivity, see equation (2.2). So marginal integration yields the function m

α

up to a constant

that can easily be estimated by the average over the observations Y

i

. We estimate the right hand

side of equation (2.3) by replacing the expectation by an average and the unknown mutidimensional

regression function m by a pre-smoother ˜m. Certainly, having a completely additive separable model

of the form

m(X)=c +

d

α=1

m

α

(X

α

), (2.5)

this method can be applied to estimate all components m

α

, and finally the regression function m is

estimated by summing up an estimator ˆc of c with the estimates ˆm

α

.

2.1 Formal Definition

Although the pre-smoother ˜m could be calculated applying any smoothing method, theory has al-

ways been derived for kernel estimators [note that the same happened to the backfitting (Opsomer

and Ruppert 1997, Mammen, Linton and Nielsen 1999)]. Therefore we will concentrate only on the

kernel based definitions even though spline implementation is known to be computationally more

advantageous. We first give the definition of the classic marginal integration method (CMIE). Let

K

i

(·)(i =1, 2) denote one - and (d −1) - dimensional Lipschitz - continuous kernels of order p and q,

respectively, with compact support, and define for a bandwidth h

i

> 0, i =1, 2, t

1

∈ IR, t

2

∈ IR

d−1

K

1,h

1

(t

1

)=

1

h

1

K

1

(

t

1

h

1

),K

2,h

2

(t

2

)=

1

h

d−1

2

K

2

(

t

2

h

2

). (2.6)

4

For the sample (X

i

, Y

i

)

n

i=1

, X

i

= (X

i1

,...,X

id

)

T

the CMIE is defined by

ˆm

α

(x

α

)=

1

n

n

j=1

˜m(x

α

,X

j,−α

)=

1

n

2

n

k=1

n

j=1

K

1,h

1

(X

jα

− x

α

)K

2,h

2

(X

j,−α

− X

k,−α

)Y

j

ˆ

f(x

α

,X

k,−α

)

(2.7)

ˆ

f(x

α

,x

−α

)=

1

n

n

i=1

K

1,h

1

(X

i,α

− x

α

)K

2,h

2

(X

i,−α

− x

−α

) (2.8)

ˆc =

1

n

n

j=1

Y

j

(2.9)

and X

i,−α

denotes the vector X

i

without the component X

iα

. Note that

ˆ

f is an estimator of the joint

density of X and ˜m denotes the Nadaraya Watson estimator with kernel K

1,h

1

· K

2,h

2

.

The modification giving us the internalized marginal integration estimate (IMIE) concerns the defini-

tion of ˆm, equation (2.7), where

ˆ

f(x

α

,X

k,−α

) is substituted by

ˆ

f(X

jα

,X

j,−α

), see Jones, Davies and

Park (1994) or Kim, Linton and Hengartner (2000) for details. The resulting definition of the IMIE is

ˆm

I

α

(x

α

)=

1

n

2

n

k=1

n

j=1

K

1,h

1

(X

jα

− x

α

)K

2,h

2

(X

j,−α

− X

k,−α

)Y

j

ˆ

f(X

jα

,X

j,−α

)

(2.10)

=

1

n

n

j=1

K

1,h

1

(X

jα

− x

α

)

ˆ

f

−α

(X

j,−α

)

ˆ

f(X

jα

,X

j,−α

)

Y

j

, (2.11)

where

ˆ

f

−α

is an estimate of the marginal density f

−α

. Notice that the fraction before Y

j

in (2.11)

is the inverse of the conditional density f

α|−α

(X

α

|X

−α

). It is well known that under the hypothesis

of an additive model ˆm

α

and ˆm

I

α

are consistent estimates of m

α

(α =1,...,d) (see Tjøstheim and

Auestad, 1994, and Kim, Linton and Hengartner, 2000).

2.2 On a Better Understanding of Marginal Integration

Although the papers of Nielsen and Linton (1997) and Sperlich, Linton and H¨ardle (1999) already

emphasized the differences of backfitting and marginal integration, often they are still interpreted as

competing estimators for the same aim. For a better understanding of the difference between orthog-

onal projection into the additive space (backfitting) and measuring the marginal impact (marginal

integration) we give two more examples.

As has been explained in Stone (1994) and Sperlich, Tjøstheim and Yang (2000), any model can be

written in the form

m(x)=c +

d

α=1

m

α

(x

α

)+

1≤α<β≤d

m

αβ

(x

α

,x

β

)+

1≤α<β<γ≤d

m

αβγ

(x

α

,x

β

,x

γ

)+··· . (2.12)

The latter mentioned article, even when they worked it out in detail only for second order interactions,

showed that all these components can be identified and consistently estimated by marginal integration

obtaining the optimal convergence rate in smoothing. The main reason for this nice property is, that

definition, algorithm and thus the numerical results for the estimates do not differ whatever the chosen

extension or the true model is. This certainly is different for an orthogonal projection. At first we note

that so far model (2.12) can not be estimated by backfitting. Secondly, Stone (1994) gives (formal)

5