FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF S T

.

LOUIS

RE V I EW

SEPTEMBER

/

OCTO B E R

201 1 325

A Comprehensive Revision of the

U.S. Monetary Services (Divisia) Indexes

Richard G. Anderson and Barry E. Jones

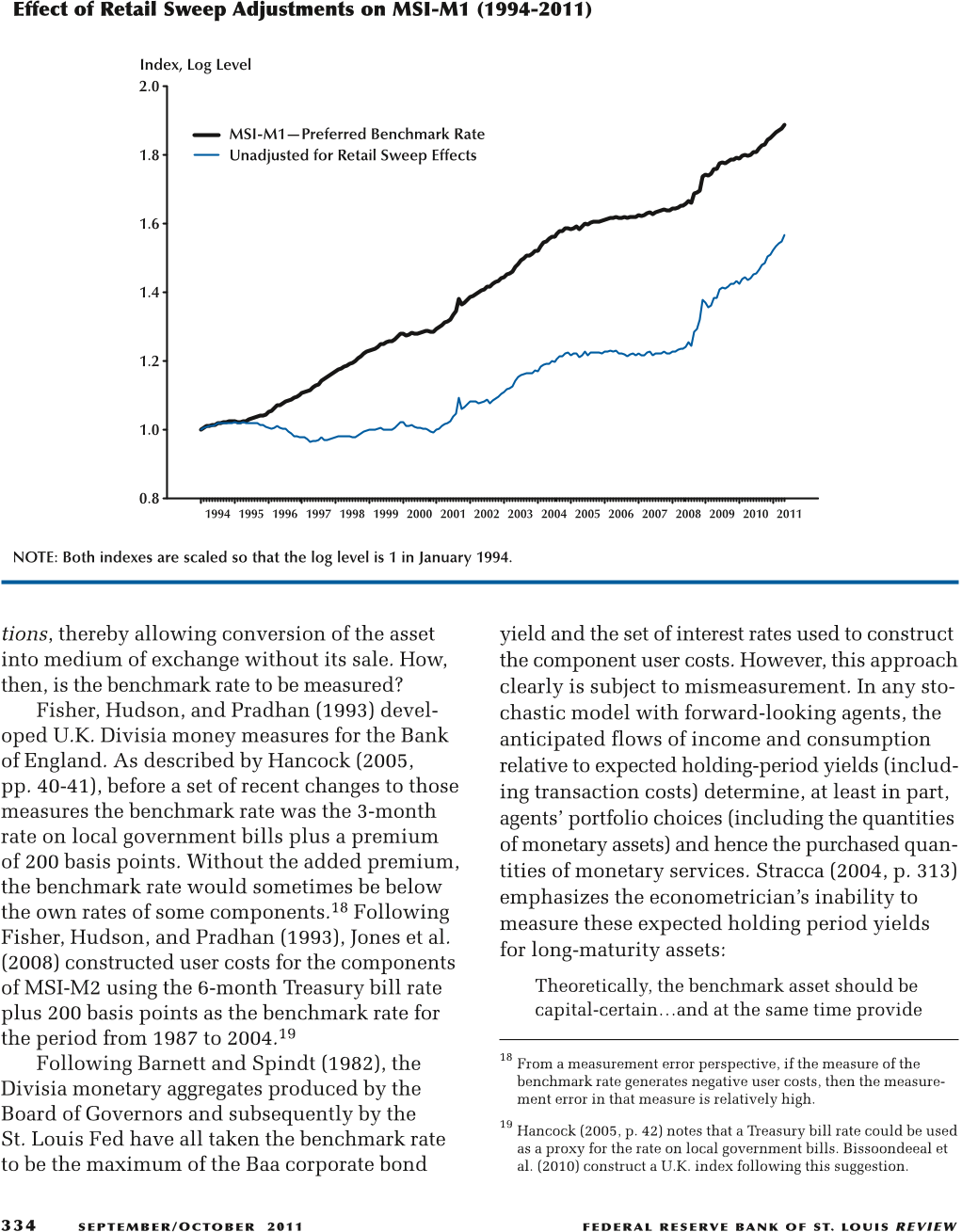

The authors introduce a comprehensive revision of the Divisia monetary aggregates for the

United States published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, referred to as the Monetary

Services Indexes (MSI). These revised MSI are available at five levels of aggregation, including a

new broad level of aggregation that includes all of the assets currently reported on the Federal

Reserve’s H.6 statistical release. Several aspects of the new MSI differ from those previously pub-

lished. One such change is that the checkable and savings deposit components of the MSI are now

adjusted for the effects of retail sweep programs, beginning in 1994. Another change is that alter-

native MSI are provided using two alternative benchmark rates. In addition, the authors have sim-

plified the procedure used to construct the own rate of return for small-denomination time deposits

and have discontinued the previous practice of applying an implicit return to some or all demand

deposits. The revised indexes begin in 1967 rather than 1960 because of data limitations.

(JEL C43, C82, E4, E50)

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October 2011, 93(5), pp. 325-59.

financial assets selected by consumers and firms

may be separated into two groups. Some assets,

including currency and checkable bank deposits,

are innately medium of exchange—that is, usable

in the purchase and sale of goods and services—

while others cannot be used until converted to

medium of exchange.

1

Generally, monetary assets

that differ in terms of their potential usefulness

as medium of exchange also differ in their own

rates of return. Barnett (1980) developed the

concept and theory of monetary index numbers,

Money is necessary to the carrying on of trade.

For where money fails, men cannot buy, and

trade stops.

—John Locke, Further Considerations

Concerning Raising the Value of Money

(1696, p. 319; quoted by Vickers, 1959)

M

oney plays a crucial role in the econ-

omy because the purchase and sale of

goods and services is settled in what

economists refer to as “medium of exchange.”

Forward-looking consumers and firms determine

their desired quantities of medium of exchange

at approximately the same time as they (i) form

expectations of future income and expenditure

and (ii) make decisions regarding desired quan-

tities of financial and nonfinancial assets. The

1

There are exceptions, of course. Bank checks, for example, are not

accepted by all merchants. Even for currency, there are exceptions

(see Twain, 1996). More seriously, currency issued by a sovereign

country often is not accepted in other countries; for a discussion

of monetary index numbers defined across currencies, see Barnett

(2007).

Richard G. Anderson is an economist and vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and visiting professor, Management School,

University of Sheffield (U.K.). Barry E. Jones is associate professor of economics at Binghamton University–State University of New York. The

authors thank Yang Liu and Esha Singha for research assistance and Barry Cynamon, Livio Stracca, and Jim Swofford for helpful comments

on an earlier draft. Anderson thanks the research department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis for their hospitality during the com-

pletion of this analysis. Jones thanks the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the department of economics at Lund University for their

hospitality during several visits.

©

2011, The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the Federal Reserve System, the Board of Governors, or the regional Federal Reserve Banks. Articles may be reprinted, reproduced,

published, distributed, displayed, and transmitted in their entirety if copyright notice, author name(s), and full citation are included. Abstracts,

synopses, and other derivative works may be made only with prior written permission of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

which he referred to as “Divisia monetary aggre-

gates.” Divisia aggregates measure, in a method

consistent with intertemporal microeconomic

theory, the aggregate flow of monetary services

derived by consumers and firms from a collec-

tion of monetary assets with different character-

istics and different rates of return. Underlying

Divisia monetary aggregates is the concept of the

user cost of a monetary asset, which is a func-

tion of the interest forgone by holding a specific

asset rather than an alternative asset that does

not provide any monetary services and earns a

higher rate of return (referred to as the “bench-

mark rate”). The close connection in microeco-

nomic theory between monetary index numbers

and agents’ anticipated income and expenditure

suggests that monetary index numbers should

be more closely related to economic activity than

conventional simple sum monetary aggregates

(see, for example, Hancock, 2005; Barnett and

Chauvet, 2011; Barnett, forthcoming).

THE MACROECONOMICS OF

MONETARY AGGREGATION

This article discusses how to construct mon-

etary index numbers (Divisia monetary aggregates)

for the United States.

2

For the most part, we do

not address when or why such measurement and

aggregation might be desirable, which is contro-

versial to some extent among macroeconomists.

The extant principal body of current macroeco-

nomic analysis widely uses the concept of an

aggregate measure of money and distinctly sepa-

rates “money” from other assets, financial and

nonfinancial.

3

Typically, macroeconomists define

“money” as financial assets that either are medium

of exchange or convertible to medium of exchange

at de minimus cost. Demand for such assets is

motivated in a macroeconomic model by either

cash-in-advance or shopping-time constraints or

a money-in-the-utility (or production) function

specification.

4

Models differ, however, regarding

whether a household or firm might replenish a

depleted stock of money during the current period

by selling (or using as collateral) its nonmonetary

assets. If such a mechanism is permitted, the cor-

rect definition of a monetary aggregate for macro-

economic analysis depends on assumptions

regarding the liquidity of those assets that are not

medium of exchange.

A complementary, but alternative, line of

thought argues that (i) the concept of a monetary

aggregate in macroeconomics is unnecessary and

misleading and (ii) models should focus on the

functions of financial assets, including as a

medium of exchange and an intertemporal store

of value. Monetary aggregates, for example, have

no role in the class of recent search-based macro-

economic models that Stephen Williamson and

Randall Wright have labeled “New Monetarist

economics.”

5

Although the exchange of goods

and services is fundamental in such models, the

role of an asset as a medium of exchange is unim-

portant because the models (implicitly or explic-

itly) assume a transformation technology such

that (almost) any asset can fulfill the functional

role of medium of exchange—that is, all assets

are liquid. For example, Williamson and Wright

(2010, p. 294) write:

Note as well that theory provides no particular

rationale for adding up certain public and pri-

vate liabilities (in this case currency and bank

deposits), calling the sum money, and attach-

ing some special significance to it. Indeed,

there are equilibria in the model where cur-

rency and bank deposits are both used in some

of the same transactions, both bear the same

rate of return, and the stocks of both turn over

once each period. Thus, Friedman, if he were

alive, might think he had good reason to call

the sum of currency and bank deposits money

and proceed from there. But what the model

tells us is that public and private liquidity play

Anderson and Jones

326

SEPTEMBER

/O

CTO B E R

201 1

FEDERAL RESERV E B A N K OF ST

.

LOUIS

RE V I EW

2

Throughout this analysis, the term “monetary assets” refers to those

financial assets that can provide “monetary services” during the

period—that is, they can serve as a medium of exchange. Some

assets (currency, checkable deposits) are immediately medium

of exchange. Other assets have the standby capability to act as

medium of exchange if there exist markets that allow the assets to

be exchanged for medium of exchange when need be, either by

means of a sale or use as collateral.

3

Walsh (2010) is a comprehensive recent textbook treatment.

4

A classic analysis is King and Plosser (1984).

5

Williamson and Wright (2010, 2011).

quite different roles. In reality, many assets are

used in transactions, broadly defined, includ-

ing Treasury bills, mortgage-backed securities,

and mutual fund shares. We see no real pur-

pose in drawing some boundary between one

set of assets and another, and calling members

of one set money.

New Monetarist-style models seek to illustrate

how a demand for monetary services arises as a

result of optimizing behavior by households and

firms. To do so, generally speaking, the models

assert that a shortage of medium of exchange is

costly in the sense that trades do not occur that

otherwise would be Pareto welfare-improving.

In such models, most financial assets are treated

as near-perfect substitutes; the role of the trans-

action costs entailed in exchanging an asset that

does not furnish medium of exchange services

for one that does is secondary, such that even

mortgage-backed securities furnish medium of

exchange (that is, monetary) services.

In a related recent analysis that addresses

neither the wisdom nor the necessity of monetary

aggregation, Holmström and Tirole (2011) ask if

transaction costs and “sudden stops” in financial

markets explain why households and firms choose

to hold larger quantities of highly liquid assets

than is suggested by models with de minimus

asset-market transaction costs. They note: “While

some forms of equity, such as private equity, may

not be readily sold at a ‘fair price,’ many long-

term securities are traded on active organized

exchanges…liquidating one’s position…can be

performed quickly and at low transaction costs”

(p. 1). Their analysis implies that not all financial

assets are perfect substitutes due to the risks that

(i) market trading might suddenly halt, (ii) differ-

ential user costs can arise in the solution to the

optimization problem facing households and

firms, and (iii) such differential user costs reflect

the differing amounts of monetary services fur-

nished by the assets.

THE ROLE OF THE FEDERAL

RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has

published monetary index numbers (initially

referred to as Divisia monetary aggregates and,

later, as Monetary Services Indexes [MSI]) for

two decades, beginning with Thornton and Yue

(1992) and continuing with Anderson, Jones,

and Nesmith (1997a,b,c) and Anderson and Buol

(2005). Publication of the most recent series was

suspended in March 2006 when certain necessary

data became unavailable.

In this paper, we introduce a comprehensive

revision of the MSI constructed at five levels of

aggregation: MSI-M1, MSI-M2, MSI-M2M, MSI-

MZM, and MSI-ALL. MSI-M1 and MSI-M2 are

constructed, respectively, over the same compo-

nents included in the Federal Reserve Board’s

M1 and M2 monetary aggregates. MSI-ALL is con-

structed over all assets currently reported on the

Federal Reserve Board’s H.6 statistical release

(the components of M2 plus institutional money

market mutual funds [MMMFs]) and is the broad-

est level of aggregation that currently can be con-

structed from available data. Finally, MSI-M2M

and MSI-MZM are zero-maturity indexes (i.e.,

they exclude small-denomination time deposits).

One change to the indexes is the adjustment of

checkable and savings deposit components of

the MSI for the effects of retail sweep programs,

beginning in 1994.

Several changes have been made to the user

costs of the components. Among these, we dis-

continued the previous practice of assigning an

implicit return to some or all demand deposits

and simplified the procedure used to construct

the own rate for small-denomination time deposits.

We also improved measures of savings and small

time deposit rates in the Regulation Q era; as a

consequence, the start date of the MSI has been

changed from 1960 to 1967. Finally, the MSI are

now constructed using two different benchmark

rates. Our preferred benchmark rate is the maxi-

mum taken over the own rates of the components

of MSI-ALL and a set of short-term money market

rates (referred to in the literature as the “upper

envelope”) plus a small liquidity premium. The

alternative benchmark rate is the larger of our

preferred benchmark rate and the Baa bond yield.

Previous practice had been to simply include the

Baa bond yield in the upper envelope.

The remainder of the paper is organized as

follows. The next section provides a brief over -

Anderson and Jones

FEDERAL RESERV E B A N K OF ST

.

LOUIS

RE V I EW

SEPTEMBER

/

OCTO B E R

201 1 327

view of the theory behind the MSI. We then

describe the MSI and their changes relative to

Anderson, Jones, and Nesmith (1997c). Next, we

examine the empirical properties of the MSI,

emphasizing the time-series behavior of the

indexes. The final section offers some conclusions.

MONETARY AGGREGATION AND

INDEX NUMBER THEORY

This section briefly reviews the economic

theory of monetary aggregation. Readers interested

primarily in the data may skip this section with-

out loss of continuity; readers seeking a more

comprehensive survey might consult Anderson,

Jones, and Nesmith (1997b).

The user cost of a monetary asset, defined as

the interest income forgone by holding a specific

financial asset rather than a higher-yielding asset

that does not provide monetary services, plays

an essential role in monetary aggregation theory.

Divisia monetary aggregates are chain-weighted

superlative indexes constructed over the quanti-

ties and user costs of selected sets of monetary

assets. The earliest Divisia aggregates for the

United States were constructed at the Federal

Reserve Board through the mid-1980s by Barnett,

Offenbacher, and Spindt (1981) and, later, by Farr

and Johnson (1985), who introduced the descrip-

tive label “Monetary Services Indexes.”

6

Background

Barnett (1978, 1980) developed Divisia mone-

tary aggregates from aggregation and index num-

ber theory; see Barnett and Serletis (2000) for a

comprehensive overview. The basic ideas can be

illustrated with a simple money-in-the-utility

function model. In each period t, a representative

consumer is assumed to maximize lifetime utility:

where c

s

denotes a vector of quantities of a set of

nonmonetary goods and services and m

s

denotes

β

s t

s t

s s

u

−

=

∞

∑

( )

c m, ,

a vector of real stocks of a set of monetary assets.

The budget constraints are given by

for all s ≥ t, where b

s

denotes the real stock of a

benchmark asset that does not enter into the util-

ity function, Y

s

represents nominal income not

due to asset holdings, p

*

s

is a price index used to

convert nominal stocks to real terms, p

s

is the

price vector for the nonmonetary goods and serv-

ices, R

s

is the nominal rate of return on the bench-

mark asset, and r

n

,s

is the nominal own rate of

return (possibly zero) for the nth monetary asset.

The user cost of each monetary asset is

derived from the above maximization. Barnett

(1978) derived the formula for the user cost of a

monetary asset by combining individual-period

budget constraints into a single lifetime budget

constraint. When optimizing in period t, current-

period real money balances, m

n,t

, are multiplied

in the lifetime budget constraint by

π

n,t

= p

*

t

u

n,t

,

where

Consequently,

π

n,t

is the user cost for m

n,t

.

7

Usually,

π

n,t

is referred to as the “nominal user

cost” and u

n,t

as the corresponding “real user cost”

(Barnett, 1987, p. 118). In an alternative derivation,

Donovan (1978, pp. 682-86) obtained the same

expression by applying the user cost formula

for a durable good to interest-bearing monetary

assets.

8

Diewert (1974, p. 510) did the same for

non-interest-bearing assets.

p c

s

s s s s s s

s n s n s

p b R p b

p m r

⋅ = +

( )

−

+ +

( )

−

−

− −

1

1

1 1

1

1

*

*

*

, ,

−−

+

=

∑

p m Y

s n s

n

N

s

*

,

1

u

R r

R

n t

t n t

t

,

,

.=

−

+1

Anderson and Jones

328

SEPTEMBER

/O

CTO B E R

201 1

FEDERAL RESERV E B A N K OF ST

.

LOUIS

RE V I EW

6

Divisia money measures for the United Kingdom have been main-

tained by the Bank of England since the early 1990s (see Fisher,

Hudson, and Pradhan, 1993, and Hancock, 2005).

7

More generally, when optimizing in period t, the (discounted)

user cost for m

n,s

共s ≥ t+1兲 is given by

See Barnett (1978) for further discussion. Diewert (1974) provides

analogous expressions for durable goods.

8

The user cost of a durable good is the difference between the pur-

chase price of a unit of the good and the present value of the sale

price one period later (adjusted for depreciation). Donovan’s argu-

ment is as follows: Holding p

*

t

dollars of a monetary asset in period

t is equivalent to holding one real dollar of the monetary asset.

p

R r

R R R

s

s n s

t t s

*

−

+

( )

+

( )

+

( )

+

,

.

1 1 1

1

A key property in aggregation and index

number theory is weak separability. In the present

context, monetary assets are weakly separable

from the other goods and services included in

the utility function if

where U is strictly increasing in V (see Varian,

1983, p. 104). Under weak separability, utility

maximization in period t implies that the vector

of real money balances, m

t

, chosen in that period

maximizes the sub-utility function, V共m兲, subject

to the budget constraint, π

t

.

m = π

t

.

m

t

, where π

t

is a vector of nominal user costs.

9

Chain-weighted superlative indexes con-

structed from data on the quantities of monetary

assets and their user costs can be used to measure

how V共m

t

兲 evolves over time; here, we provide

an overview (see the appendix for details). Specifi -

cally, the MSI are based on the superlative

Törnqvist-Theil formula. The chain-weighted

Törnqvist-Theil monetary quantity index is

where

is the expenditure share for the nth monetary

asset for period t. The index has the attractive

property that its log difference is a weighted aver-

age of the log differences of its components:

u U Vc m c m, , ,

( )

≡

( )

V V

m

m

t t

n t

n t

n

N

w w

n t n t

=

∏

−

−

=

+

−

1

1

1

2

1

,

,

, ,

,

w

m

m

n t

n t n t

i t i t

i

N

,

, ,

, ,

=

=

∑

π

π

1

Barnett (1980) interpreted the Törnqvist-Theil

index as a discrete-time approximation of the

continuous-time Divisia index, which is the origin

of the term Divisia monetary aggregate. As he

emphasized, in continuous time the Divisia index

is exact for any linearly homogeneous utility

function.

10

The MSI and Their Dual User Cost

Indexes

The published St. Louis MSI are constructed

from nominal rather than real monetary asset

quantities and, in that sense, are nominal mone-

tary index numbers; corresponding real MSI can

be obtained by dividing the nominal MSI by a

price index. We also publish real user cost indexes

for the various MSI that are suitable for use in

empirical work as the opportunity costs of those

MSI. The real user cost indexes can be multiplied

by a price index to obtain corresponding nominal

user cost indexes. This is analogous to the rela-

tionship between real and nominal user costs of

individual monetary assets as discussed above.

Specifically, let p

t

*

denote a price index, and

let M

n,t

and m

n,t

denote the nominal and real

quantities, respectively, of the nth monetary

asset—that is, m

n,t

= M

n,t

/p

t

*

. Let u

n,t

be the corre-

sponding real user cost, which does not depend

on the price index. The corresponding nominal

user cost is

π

n,t

=p

t

*

u

n,t

. The published nominal

MSI are constructed using nominal monetary

asset quantities as follows:

ln ln

ln

,

,

,

V V

w w

m

t t

n

t n t

n

N

n

t

( )

−

( )

=

+

( )

−

−

=

∑

1

1

1

2

−−

( )

−

ln .

,

m

n

t 1

MSI MSI

M

M

t t

n t

n t

n

N

w w

n t n t

=

−

−

=

+

∏

−

1

1

1

2

1

,

,

, ,

.

Anderson and Jones

FEDERAL RESERV E B A N K OF ST

.

LOUIS

RE V I EW

SEPTEMBER

/

OCTO B E R

201 1 329

Thus, the purchase price of a real dollar of the monetary asset is

p

*

t

and the sale price of a real dollar of the asset one period later is

p

*

t+1

. If the asset earns interest, holding p

*

t

dollars of the asset for

one period results in p

*

t

共1 + r

n,t

兲/p

*

t+1

real dollars of the asset one

period later. Consequently, the user cost of the monetary asset is

9

Barnett (1982) emphasizes weak separability in choosing the

components of a monetary aggregate. Varian (1982, 1983) derived

necessary and sufficient conditions for a dataset to be consistent

with utility maximization and weak separability. A number of

studies have applied tests of these conditions to determine if spe-

cific groupings of monetary assets are weakly separable. For recent

examples, see Jones, Dutkowsky and Elger (2005), Drake and

Fleissig (2006), and Elger et al. (2008).

p p

p r

p R

p

R r

R

t t

t n t

t t

t

t n t

t

* *

*

*

*

−

+

( )

+

( )

=

−

+

=

+

+

1

1

1

1

1

,

,

ππ

n t,

.

10

If m

t

maximizes V共m兲 subject to the budget constraint π

t

.

m =

π

t

.

m

t

for all t and V共m兲 is linearly homogeneous, then in the

continuous-time case

which corresponds to the continuous-time Divisia quantity index

(see Barnett, 1987, p. 141).

d V

dt

d V

dt

w

d m

dt

t

t

n t

n

N

n t

ln

ln

ln

,

,

( )

=

( )

( )

=

( )

=

∑

m

,

1