University of Nebraska - Lincoln

DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln

Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of

5-2006

A Coprological View of Ancestral Pueblo

Cannibalism

Karl Reinhard

University of Nebraska-Lincoln, kreinhard1@mac.com

Follow this and additional works at: h9p://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard

Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Other Public Health Commons, and the

Parasitology Commons

8is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It

has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska -

Lincoln.

Reinhard, Karl, "A Coprological View of Ancestral Pueblo Cannibalism" (2006). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 26.

h9p://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/26

254

A

s the object of my scientic study,

I’ve chosen coprolites. It’s not a

common choice, but to a paleonutri-

tionist and archaeoparasitologist, a

coprolite—a sample of ancient feces

preserved by mineralization or simple

drying—is a scientic bonanza. Analy-

sis of coprolites can shed light on both

the nutrition of and parasites found in

prehistoric cultures. Dietary reconstruc-

tions from the analysis of coprolites can

inform us about, for example, the ori-

gins of modern Native American diabe-

tes. With regard to parasitology; copro-

lites hold information about the ancient

emergence and spread of human infec-

tious disease. Most sensational, how-

ever, is the recent role of coprolite anal-

ysis in debates about cannibalism.

Most Americans know the people

who lived on the Colorado Plateau

from 1200 B.C. onward as the Anasazi,

a Navajo (or Dine) word. The modern

Pueblo people in Arizona and New

Mexico, who are their direct descen-

dants, prefer the description Ancestral

Pueblo or Old Ones. Because the image

of this modern culture could be tainted

by the characterization of their ances-

tors, it’s especially important that ar-

chaeologists and physical anthropol-

ogists come to the correct conclusion

about cannibalism. This is the story of

my involvement in that effort.

When a coprolite arrived in my lab-

oratory for analysis in 1997, I didn’t

imagine that it would become one of

the most contentious nds in archaeo-

logical history. Banks Leonard, the Soil

Systems archaeologist who directed ex-

cavation of the site at Cowboy Wash,

Utah, explained to me that there was

evidence of unusual dietary activity by

the prehistoric individual who depos-

ited the coprolite. He or she was possi-

bly a cannibal.

I had been aware of the cannibalism

controversy for a number of years, and

I was interested in evaluating evidence

of such activity. But from my scientic

perspective, it was simply another sam-

ple that would provide a few more data

points in my reconstruction of ancient

diet from a part of the Ancestral Pueblo

region that was unknown to me.

The appearance of the coprolite was

unremarkable—in fact, it was actually

a little disappointing. It looked like a

plain cylinder of tan dirt with no obvi-

ous macrofossils or visible dietary in-

clusions. I have analyzed hundreds of

Ancestral and pre-Ancestral Pueblo

coprolites that were more interesting.

Indeed, I have surveyed tens of thou-

sands more that, to my experienced eye,

held greater scientic promise. Yet this

one coprolite, when news of it hit the

media, undid 20 years of my research

on the Ancestral Pueblo diet. On a

broader scale, it caused the archaeolog-

ical community to rethink our percep-

tion of the nature of this prehistoric cul-

ture and to question what is reasonable

scientic proof.

Cannibalism, Without Question

In the arid environment of the U.S.

Southwest, feces dried in ancient throes

provide a 9,000-year record of gastro-

nomic traditions. This record allows me

and a few other thick-skinned research-

ers to trace dietary history in the deserts.

(I say “thick-skinned,” because analysts

generally don’t last long in this specialty.

Many have done one coprolite study,

only to move on to a more socially ac-

ceptable archaeological specialty.)

From the mid-1980s to the mid-’90s, I

had characterized the Ancestral Pueblo

lifestyle as a combination of hunting

and gathering mixed with agriculture

based on the analysis of about 500 cop-

rolites from half a dozen sites. Before

me, Gary Fry, then at Youngstown State

University, had come to the same con-

clusion in work he published during

the ‘70s and ‘80s, based on the analysis

of a large number of Ancestral Pueblo

coprolites from many sites. These peo-

ple were nely attuned to the diverse

and complicated habitats of the Colo-

rado Plateau for plant gathering, as well

as for plant cultivation. The Ancestral

Pueblo certainly ate meat—many kinds

of meat—but never had there been any

indication of cannibalism in any copro-

lite analysis from any site.

The evidence for cannibalism at

Cowboy Wash has been widely pub-

lished. A small number of people were

Published in American Scientist 94:3 (May/June 2006), pp. 254-261.

Copyright © Sigma XI Science Research Society. Used by permission.

A Coprological View of Ancestral Pueblo

Cannibalism

Debate over a single fecal fossil offers a cautionary tale

of the interplay between science and culture

Karl J. Reinhard

Karl J. Reinhard is a professor in the School of Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska and a Fulbright Commission Senior Specialist

in Archaeology for 2004-2009. The main focus of his career since earning his Ph.D. from Texas A&M has been to nd explanations for mod-

ern patterns of disease in the archaeological and historic record. He also developed a new specialization called archaeoparasitology, which

attempts to understand the evolution of parasitic disease. Address: 309 Biochemistry Hall, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 48503-0578.

Figure 1. What was the nature of the people

who occupied much of the Colorado Plateau

for two and a half millennia up until about

1300 A.D.? Commonly known by the Navajo

term Anasazi, the Ancestral Pueblo were

considered the “peaceful people” until they

were accused of cannibalism in 1990s. The

answer is more than academic, as their de-

scendants still occupy the southerly reaches

of the Ancestral Pueblo domain. The author

has studied hundreds of Ancestral Pueblo

coprolites—dried or fossilized feces—and

has found all but one to contain residues of a

diverse mixture of plant matter, both domes-

ticated and wild, and meat. Only one shows

evidence of cannibalism. Should that single

sample be used to condemn an entire cul-

ture? The human efgy shown here is from

Pueblo III culture, circa 700-1100 A.D.

A Co pr o lo g iC A l Vi e w o f AnC e st r Al pu e bl o CA n n i b A li s m 255

The Art Archive/Southwest Museum/Pasadena/Laurie Pratt Winfrey

256 KAr l re in h Ar d i n A m e r i c A n S c i e n t i S t 94:3 (m A y /Jun e 2006)

undoubtedly killed, disarticulated and

their esh exposed to heat and boiling.

This took place in a pit house typical

of the Ancestral Pueblo circa 1200 A.D.

At the time of the killings, the appear-

ance of the pit house must have been

appallingly gruesome. Human blood

residue was found on stone tools, and

I imagine that the disarticulation of

the corpses must have left a horrifying

splatter of blood around the room. But

the most conclusive evidence of can-

nibalism did not come from the room

where the corpses were dismembered.

It came from a nearby room where

someone had defecated on the hearth

around the time that the killings took

place. The feces was preserved as a cop-

rolite and would turn out to be the con-

clusive evidence of cannibalism.

My analysis of the coprolite was not

momentous. I could determine from

its general morphology that it was in-

deed from a human being. However,

the tiny fragment that I rehydrated

and examined by several microscopic

techniques contained none of the typ-

ical plant foods eaten by the Ances-

tral Pueblo. Background pollen of the

sort that would have been inhaled or

drunk was the only plant residue that

I found. Thus, I concluded that the cop-

rolite did not represent normal Ances-

tral Pueblo diet. It seemed to represent

a purely meat meal, something that is

unheard of from Ancestral Pueblo cop-

rolite analyses.

After analyzing the Cowboy Wash

coprolite, I took a half-year sabbatical

as a Fulbright scholar in Brazil. When

I returned, I learned that my analysis

had been superseded by a new technol-

ogy. Richard Marlar from the Univer-

sity of Colorado School of Medicine and

colleagues had taken over direct anal-

ysis of the coprolite using an enzyme-

linked immunosorbent assay to detect

human myoglobin, and their work had

conrmed and expanded my analysis.

The coprolite was from a human who

had eaten another human. The technical

paper appeared in Nature and was fol-

lowed by articles in the New Yorker, Dis-

cover, Southwestern Lore and the Smith-

sonian, among many others. The articles

became the focus of a veritable explo-

sion of media pieces in the press, on ra-

dio and television, and on the Internet,

amounting to an absolute attack on An-

cestral Pueblo culture.

Initially, I sat and watched the me-

dia feeding frenzy and Internet chat de-

bates with a sense of awe and post-sab-

batical detachment. My original report

suggesting the coprolite was not of An-

cestral Pueblo origin went largely unno-

ticed. The few journalists who did call

me for an opinion proved uninterested

in publishing it. In some cases it was too

far to y to Nebraska to lm; in others

my opinion didn’t t into the context of

the debate. Well, I have looked at more

Ancestral Pueblo feces than any other

human being, and I do have an opinion:

The Ancestral Pueblo were not canni-

balistic. Cannibalism just doesn’t make

sense as a pattern of diet for people so

exquisitely adapted to droughts by cen-

turies of hunting-gathering traditions

and agricultural innovation.

Then a media quote knocked me out

of my stupor. Arizona State University

anthropologist (emeritus) Christy G.

Turner II, commenting in an interview

about a book he co-authored on Ances-

tral Pueblo cannibalism, said, “I’m the

guy who brought down the Anasazi.”

Perhaps to temper Turner’s broad gen-

eralization, Brian Billman (a coauthor of

the Marlar Nature paper) of the Univer-

sity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

suggested that a period of drought

brought on emergency conditions that

resulted in cannibalism. Beyond the sci-

entic quibbling about who ate whom

and why, I am amazed at the vortex of

debate around the Coyote Wash copro-

lite. The furor over that one coprolite

represents a new way of thinking about

the Ancestral Pueblo and archaeologi-

cal evidence.

What Did the Ancestral Pueblo Eat?

To me, a specialist in Ancestral

Pueblo diet, neither Turner’s nor Bill-

man’s explanation made sense. So, in

the years since the Nature paper ap-

peared in 2000, I have renewed my

analyses of Ancestral Pueblo coprolites

to understand just what they did eat in

times of drought. And let me say em-

phatically that Ancestral Pueblo cop-

rolites are not composed of the esh of

their human victims. Some of their di-

etary practices were, perhaps, peculiar.

I still recall in wonderment the inch-di-

ameter deer vertebral centrum that I

found in one sample. It was swallowed

whole. The consumption of insects,

snakes and lizards brought the Ances-

tral Pueblo notice in the children’s book

It Was Disgusting and I Ate It. But look-

Figure 2. Cowboy Wash, Utah, near the San

Juan River and Four Corners, is the only An-

cestral Pueblo archaeological excavation to

turn up coprological evidence of cannibal-

ism. Evidence from other sites (red dots) con-

rms the people’s diverse diet. (Topographic

map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.)

A Co pr o lo g iC A l Vi e w o f AnC e st r Al pu e bl o CA n n i b A li s m 257

ing beyond such peculiarities, their diet

was delightfully diverse and testies to

the human ability to survive in the most

extreme environments. To me, diet is

one the most fundamental bases of civ-

ilization, and the Ancestral Pueblo pos-

sessed a complicated cuisine. They were

gastronomically civilized.

Widespread analysis of coprolites

by “paleoscatologists” began in the

1960s and culminated in the ‘70s and

‘80s when graduate students worked

staunchly on their coprological theses

and dissertations. From Washington

State University, to Northern Arizona

University to Texas A & M and many

more, Ancestral Pueblo coprolites were

rehydrated, screened, centrifuged and

analyzed. Richard Hevly, Glenna Wil-

liams-Dean, John Jones, Mark Stiger,

Linda Scott-Cummings, Kate Aasen,

Gary Fry, Karen Clary, Molly Toll and

Vaughn Bryant, Jr., to name a few,

joined me in puzzling over Ancestral

Pueblo culinary habits. In their consci-

entious and rigorous research, the same

general theme emerged. The Ancestral

Pueblo were very well adapted to the

environment, both in times of feast and

in times of famine.

In general, the Ancestral Pueblo diet

was the culmination of a long period

of victual tradition that began around

9,000 years ago, when people on the

Colorado Plateau gave up hunting big

animals and started collecting plants

and hunting smaller animals. Prickly

pear cactus, yucca, grain from drop-

seed grass, seeds from goosefoot and

foods from 15 other wild plants dom-

inated pre-Ancestral Pueblo life. One

of the truly interesting dietary patterns

that emerged in the early time and con-

tinued through the Ancestral Pueblo

culture was the consumption of pol-

len-rich foods. Cactus and yucca buds

and other owers were the sources of

this pollen. Rabbit viscera probably pro-

vided a source of fungal spores of the

genus Endogane, although I doubt that

these people knew they were eating the

spores when they ate the rabbits. The

pre-Ancestral Pueblo people adapted to

starvation from seasonal food shortages

by eating yucca leaf bases and prickly

pear pads and the few other plants that

were available in such lean times.

Prey for the pre-Ancestral Pueblo peo-

ple included small animals such as rab-

bits, lizards, mice and insects. In tact,

most pre-Ancestral Pueblo coprolites

contain the remains of small animals.

My analysis of these remains shows that

small animals, especially rabbits and

mice, were a major source of protein in

summer and winter, good times and bad.

The Ancestral Pueblo per se de-

scended from this hunter-gatherer tra-

dition. Coprolite analysis shows that

they were largely vegetarian, and plant

foods of some sort are present in ev-

ery Ancestral Pueblo coprolite I have

analyzed. But these later people also

expanded on their predecessors’ cui-

sine. They cultivated maize, squash

and eventually beans. Yet they contin-

ued to collect a wide diversity of wild

plants. They actually ate more species of

wild plants—more than 50—than their

ancestors who were totally dependent

on wild species.

Adapting to the Environment

In 1992, I presented a series of hy-

potheses addressing why the Ancient

Pueblo ate so many species of wild

plants. Later, Mark Stiger of Western

State College and I went to work on the

problem using a statistical method that

he devised. We determined that the An-

cestral Pueblo encouraged the growth

of edible weedy species in the distur-

bances caused by cultivation and vil-

lage life. In doing so, they increased the

spectrum of wild edible plants avail-

able to them, often using them to spice

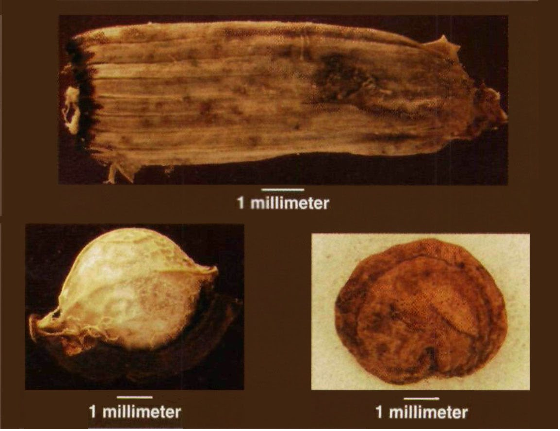

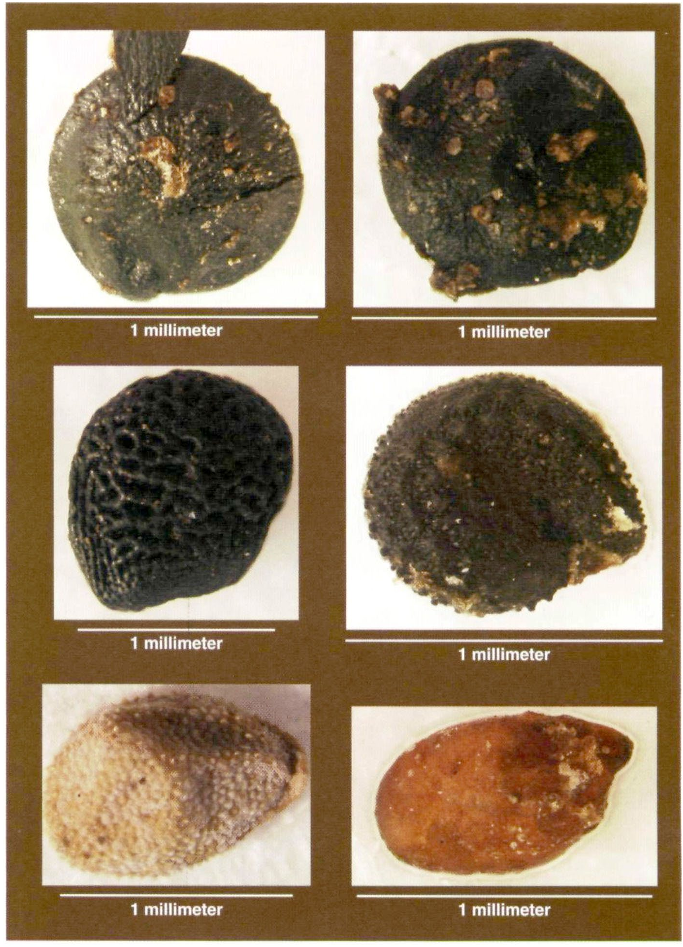

Figure 3. Small seeds were an important part of the Ancestral Pueblo diet. Because they are

typically quite small and are often fragmented from stone grinding, their identication in cop-

rolites can be difcult. Shown here (clockwise, from upper left) are seeds of pigweed, goose-

foot, purslane, dropseed grass, an unknown seed present in on|y one sample and hedge-

hog-cactus fruit. These are only a few examples of the seeds that the Ancestral Pueblo ate.

(Vegetation photographs by the author.)