Journal of Pediatric Neurology 2004; 2(2): 73-77

www.jpneurology.org

Abstract

Thirty two patients with subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis (SSPE) admitted under the

care of Department of Neurology at JJ Hospital

and Grant Medical College, Mumbai during

the period 1998-2003 were analyzed. All

patients were evaluated clinically, with relevant

investigations and neuroimaging wherever

possible. Particular attention was given to early

clinical features. Diagnosis was conrmed by

cerebrospinal uid study for measles antibody

and by electroencephalography. The mean age

of our patients was 13.4 years and the vaccinated

patients tended to be older. Nine patients had

received measles vaccination. Twelve percent of

patients were older than the age of 20 years at

the onset of symptoms. Approximately 40.6%

of patients presented with symptoms of loss of

vision, seizures and behavioral change. At this

stage myoclonus and cognitive decline were

conspicuous by their absence. Eventually typical

features like myoclonus and cognitive decline

evolved after a mean period of 8 months. Even

in the present era, SSPE continues to remain the

most important cause of progressive myoclonic

epilepsy. With progressive increase in age of

presentation, in patients with features like loss

of vision, seizures and behavioral changes, SSPE

should be carefully considered. (J Pediatr Neurol

2004; 2(2): 73-77).

Key words: early clinical features, SSPE, vision loss,

seizures.

Introduction

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is

a slowly progressive fatal inammatory disease of

the central nervous system, developing as a sequel

to childhood measles infection (1,2). Typically it

presents with myoclonus and dementia progressing

to a mute, bed-ridden and incontinent state nally

leading to death. The best accepted postulation is

that during the measles infection there is incomplete

clearance of the measles virus by the patient’s

immune system leading to persistence of incomplete

forms of the virus with aberrant M protein in the

central nervous system. This results in cell death,

inammation and gliosis (1).

The worldwide prevalence of SSPE is 0.04-2

cases per million (1,3). It has been brought down

following implementation of measles vaccination

in the developed countries (4). SSPE still exists in

the developing nations, with high incidence amongst

some ethnic groups (3,6). The pattern of clinical

presentation of SSPE has been noticed to change to

an extent over the years, while some changes have

also been noted in the laboratory features of SSPE

(1,2). SSPE still continues to take lives of children

in developing countries (6); the uncommon modes

of presentation of SSPE pose diagnostic difculties

and hence are being highlighted in this study. We

have also compared the present results with a

similar study carried out in the same department of

neurology in 1974 (7).

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in the department

of neurology of a tertiary care hospital during the

period of ve years from 1998 to 2003.

Inclusion criteria given by Dyken (1) were

followed, namely:

1. Progressive cognitive decline with stereotyped

myoclonic jerks.

2. Generalized long-interval periodic complexes in

the electroencephalography (EEG).

3. Elevated cerebrospinal uid globulin levels.

4. Elevated cerebrospinal uid measles antibody

titers.

5. Typical histological ndings in brain biopsy or

Correspondence: Dr. Satish V Khadilkar

Room no 110, First Floor,

MRC Bulding,

Bombay Hospital, Mumbai, India.

E-mail: khadilkar@vsnl.com

Received: November 02, 2003.

Revised: December 24, 2003.

Accepted: January 16, 2004.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A study of SSPE: early clinical features

Satish V. Khadilkar, Shekhar G. Patil, Kedar S. Kulkarni

Department of Neurology, Grant Medical College and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Mumbai, India

autopsy.

The diagnosis was established if three out the

ve criteria were fullled. Those patients fullling

the above criteria were selected and enrolled for the

study. Their data was obtained under the following

headings.

a. Preliminary data: name, age, sex, duration of

symptoms, history of measles, history of measles

vaccination.

b. Presence of symptoms like cognitive decline,

myoclonic jerks, seizures, loss of vision, behavioral

change, and sphincter dysfunction.

These patients were then evaluated clinically to

look for abnormalities of higher mental functions,

visual acuity, presence of chorioretinitis on fundus

examination, presence of long tract signs and motor

or sensory decit. Clinical examination was followed

by investigations including EEG, cerebrospinal uid

and serum examination to look for measles antibody

titers. Neuroimaging, wherever possible, was carried

out.

Results

A total of 32 cases were included in the study.

Twenty four of these patients were males and eight

were females. The age at presentation varied from 4

years to 21 years with a mean age of 13.4 years.

In our series 26 patients presented with cognitive

decline, while myoclonus was seen in 27 patients

(Figure 1). Almost 90% of the patients had at least

one of these two symptoms. In the remainder,

predominant seizures, loss of vision or behavioral

change were the presenting symptoms. Six patients

were incontinent by the time medical attention was

obtained. It can thus be seen that cognitive decline

and myoclonus were the essential features of the

clinical symptomatology at the initial examination.

Figure 1 also depicts the symptoms at the onset

of the disease. Relatives of two of our patients were

unable to pinpoint the exact symptom amongst

myoclonus and cognitive decline at the onset hence

in these patients we considered that both symptoms

began at the same time. Out of the 32 patients,

features like vision loss, seizures, and behavioral

changes were seen in 13 patients with one patient

having a simultaneous onset of seizures with

behavioral change (Table 1). Typical features like

myoclonus and/or cognitive decline were seen in the

remaining 19 patients. Thus in approximately 40.6%

of patients uncommon features marked the onset of

disease.

In our study nine patients were vaccinated for

measles at nine months of age. The mean age at

onset of the disease in the vaccinated group was 15.7

years as compared to 12.4 years in the unvaccinated

group. The vaccinated group had a rapid clinical

worsening as compared to the non-vaccinated group.

The average duration of illness from the onset of

rst symptom to seeking medical attention was 3.2

months in the vaccinated group while it was 6.6

months in the non-vaccinated group. By using the

Neurologic Disability Index, all the unvaccinated

and six vaccinated patients were found to have

subacute speed of progression, while three patients

in the vaccinated group had acute evolution. 23

patients were unvaccinated. Relatives of 15 patients

(65.2%) could remember the presence of measles

infection in the childhood, prior to the age of 4

years. The mean incubation period in these patients

was at least 8.13 years. Out of the four patients with

onset of illness after the age of 20 years three were

vaccinated and, the single unvaccinated patient had

suffered from measles at the age of 5 years.

Thirteen out of the 32 patients showed uncommon

features at the onset of the disease (Figure 1).

Amongst our series of 32 patients, seven patients

presented with vision loss which was attributed

to white matter lesions in the parieto-occipital

region. Out of these seven, visual loss was the rst

symptom in six patients. Three other patients had

signs of early optic atrophy but had no symptoms

of loss of vision. Thus all patients in our series had

cortical type of vision loss. Five (15.7%) patients

had onset with seizure disorder, while long tract

signs in the form of spasticity which manifested as

either hemiparesis or quadriparesis was seen in ve

(15.7%) patients. The pyramidal tract signs were

seen in later stages of the disease. The six patients

Figure 1. Clinical symptomatology.

Table 1. Uncommon clinical features at initial

examination

Features Number of Cases

Vision loss 7

Seizures 6

Behavioral change 7

Catatonia 1

Early clinical features in SSPE

S V Khadilkar et al

74

presenting with seizures had a prolonged history

of seizures, with average duration of 15 months

before cognitive decline set in. Seven patients had

behavioural changes. It was the presenting symptom

in three of them.

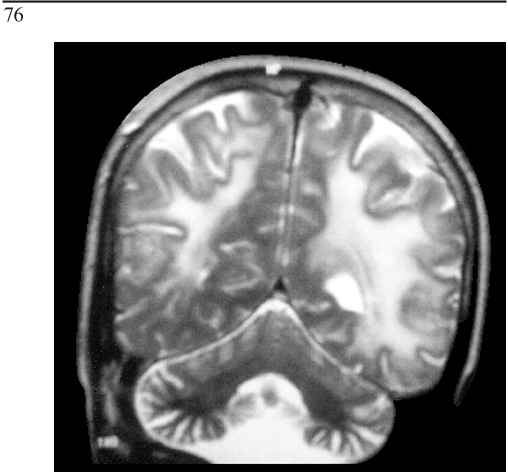

Twenty one patients were imaged in our

series. Eighteen magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) and three computed tomography (CT)

examinations were performed. Eight patients had

normal imaging ndings. Out of the remaining 13

patients abnormalities were seen in white matter,

grey matter and basal ganglia. Changes were seen

in parieto-occipital cortical and subcortical areas

with symmetric involvement of the periventricular

white matter in 10 out of 13 patients. Seven patients

in this group of white matter lesions presented with

vision loss. Three patients had involvement of white

and grey matter together while isolated involvement

of basal ganglia was seen in a single patient (Figure 2).

Discussion

SSPE is a chronic inammatory disease of the

central nervous system following childhood measles

infection which is invariably fatal. The average

age of presentation worldwide is between 5 and 15

years with the mean age being 9-10 years (1,2). The

average age of patients in our study was 13.4 years,

which is higher than other studies. This nding is

in keeping with the fact that globally the average

age of SSPE is increasing, which can be attributed

to better vaccination coverage. In the present study,

the vaccinated patients presented later than the

unvaccinated ones by 3.3 years. There are some

reports in which the average age has been shown to

have decreased following vaccination; however the

importance of this observation is unclear at present

(4,6).

In our study, patients who had been vaccinated

had more rapid course of disease, from the onset

till the diagnosis, being 3.2 months as compared to

6.6 months in the unvaccinated group. Also, acute

progression was seen only in the vaccinated patients,

but we could not nd any study to corroborate this

nding. The association of measles vaccine and

SSPE has been an issue of much importance. In

patients of SSPE who had been vaccinated, It has

been documented that the genomic structure of

the measles virus from the vaccine did not match

the virus obtained from the specimens of brain

biopsy as reported by Jin et al. (8), and measles

vaccination has not been causally associated with

the development of SSPE. Our observation of rapid

evolution of SSPE in vaccinated patients will need

further scrutiny with larger number of patients.

The higher percentage of cases of SSPE amongst

the vaccinees may be due to poor nutritional status

of children in the developing countries resulting in

poor uptake, or due to a different type of strain in

the environment, subclinical measles infection prior

to measles vaccination or due to faulty storage (cold

chain) of the vaccine. We believe that one or more

of these factors were operating in our vaccinated

children who had SSPE.

Thirteen patients presented with unusual

symptoms like loss of vision, seizures, or behavioral

changes. Though loss of vision is a well documented

symptom, studies have reported a higher incidence

of visual loss amongst patients with adult onset

SSPE with age ranging from 20-35 years (2,9,10).

However, in our study, the mean age of patients

presenting with loss of vision was 14.8 years with

Figure 2. Imaging ndings.

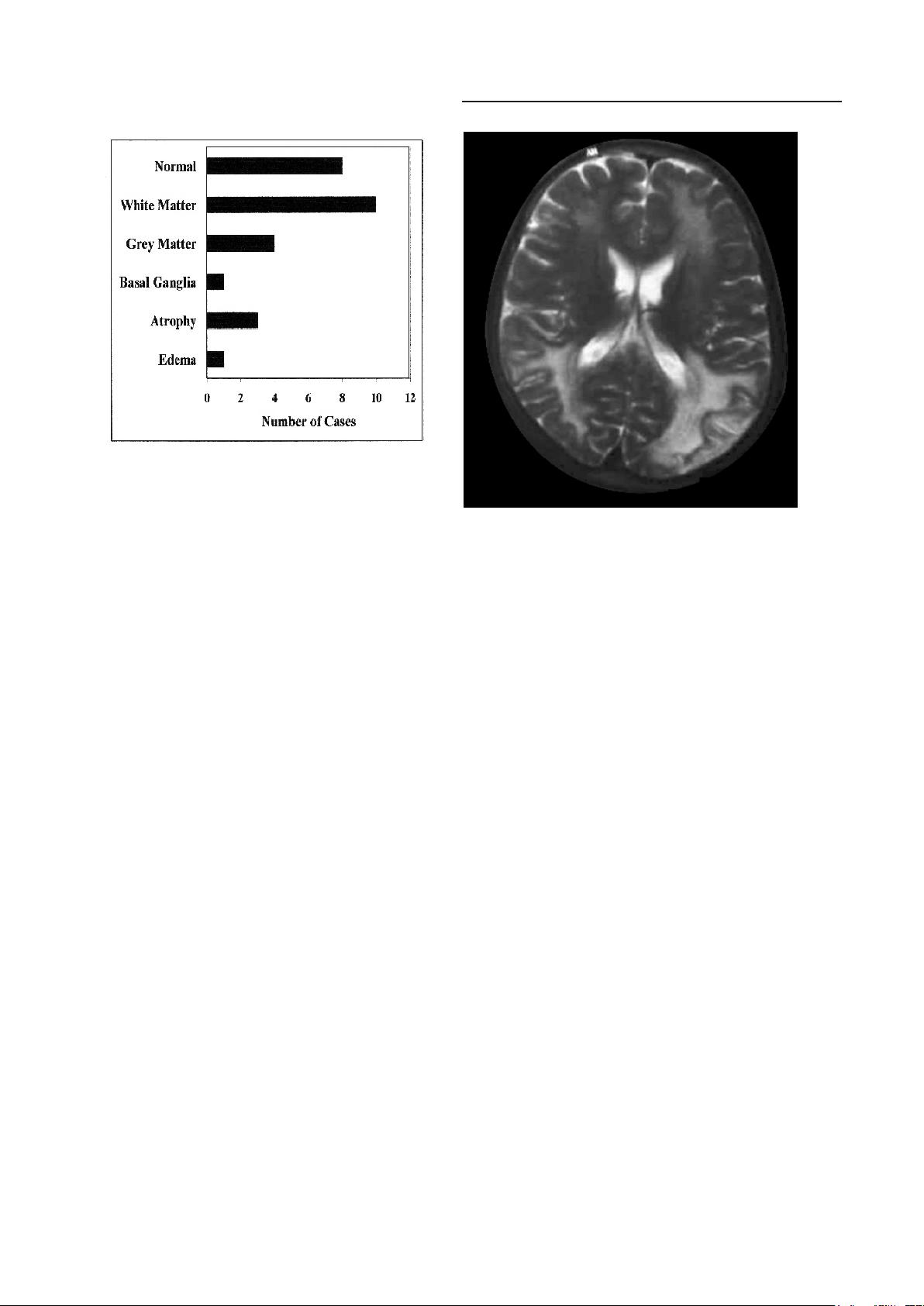

Figure 3. T2 weighted MRI showing increased signal in

the parieto-occipital white matter and grey matter.

Early clinical features in SSPE

S V Khadilkar et al

75

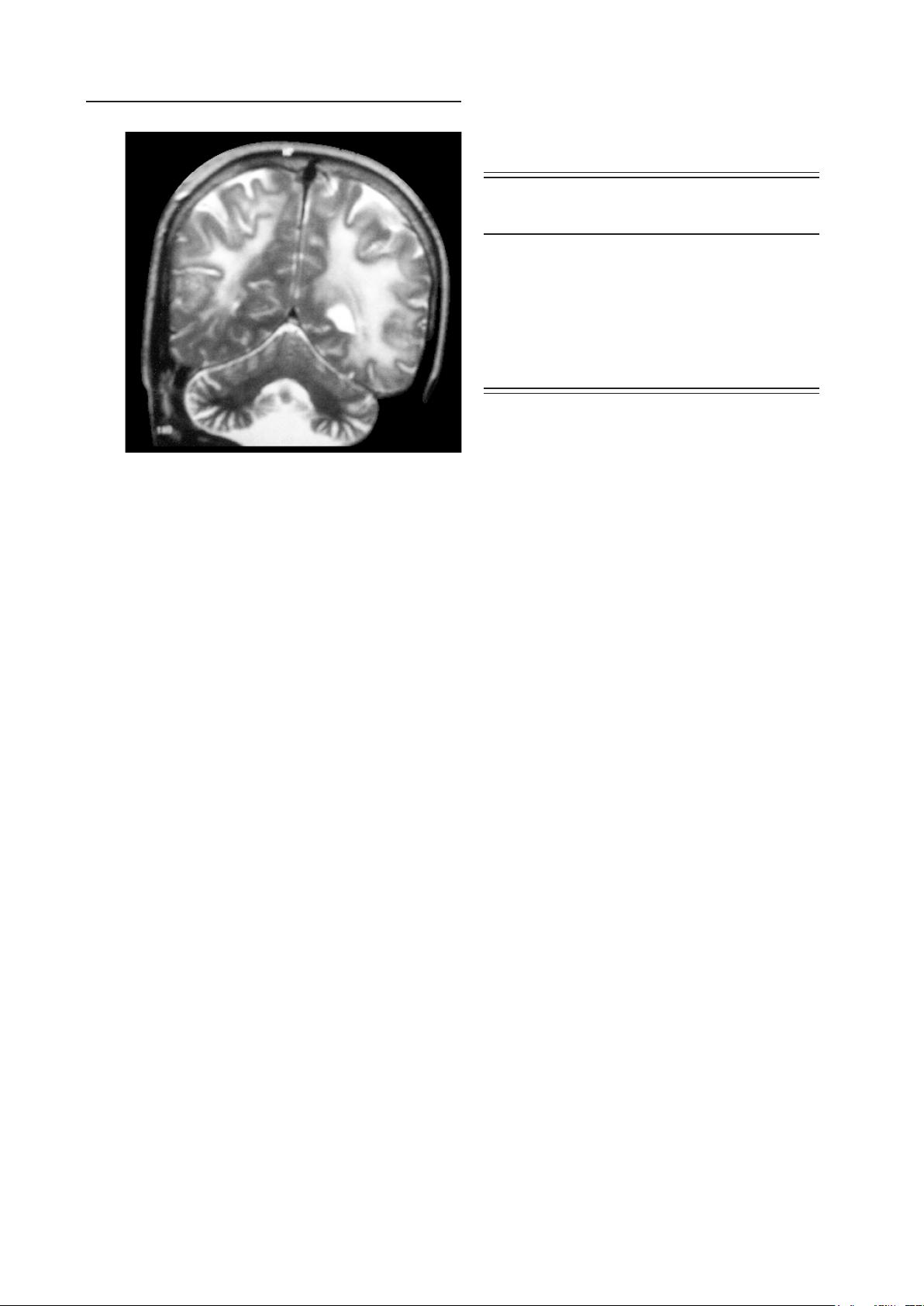

age range of 12-20 years. Visual loss was seen as

frequently with the young as with the older patients.

The vision loss in these patients was of the posterior

type with neuroimaging features suggestive of

diffuse white matter lesions in the parieto-occipital

lobes which are best seen on the T2 weighted MRI

images (Figure 3 and 4). Features suggestive of

chorioretinitis were seen in four patients, out of

which three patients also had early optic atrophy,

however loss of vision was neither reported nor found

in these four patients. Thus, at all ages, visual loss of

the occipital type formed an important feature in the

early phases of SSPE.

Those patients who presented with seizures

had a longer duration of symptomatology till the

diagnosis of SSPE. Most of these patients continued

to experience seizures in spite of anti-epileptic

medications and then they progressed slowly with

evolution of myoclonus and cognitive decline as

the time elapsed. All six patients experienced

generalized seizures, out of which four patients

began their illness with seizures alone and in the

other two such seizures were either along with or

following other symptoms respectively. Patients with

“disease revealing” seizures, as seen in ve of our

patients, had a prolonged course of symptomatology,

before cognitive decline set in. Kissani et al. (11)

documented epilepsy in 30 (42%) of their patients

in a series of 70 patients. Among these 30 patients,

“disease revealing” seizures were seen in 23%

of patients. Özturk et al. (12) had seven (19.4%)

patients with seizures in their series of 36 patients.

The incidence of seizures in our study is less as

compared to studies mentioned in literature.

Wandering behavior was noted in four patients

and it was the rst symptom in two of them. These

patients had uncontrolled urge to leave home

and would wander for hours before returning.

Irritability and adamant behavior was seen in all

the seven patients. Hyper religiosity was seen in one

patient. He used to spend most of his awake hours in

praying and worshipping. All the seven patients

gradually developed more obvious cognitive decline

and myoclonus over an average period of 5.9

months.

Out of 21 patients who underwent neuroimaging

approximately one-third of patients had normal

imaging. The most striking feature of neuroimaging

was abnormalities in the white matter mainly

involving the parieto-occipital cortical and

subcortical regions. Changes were also detected

in the grey matter and the basal ganglia but these

changes were far and few as compared to the

white matter changes. Early stages of SSPE shows

edematous change or normal imaging while later

stage of the disease shows marked atrophy of the

brain which was seen in three of our patients (13).

In our study there was no enhancement of lesions on

CT scans, but Brismar et al. (14) have reported a case

with rapid clinical deterioration and multiple areas

of enhancement on neuroimaging.

A similar study regarding clinical aspects of

SSPE was published from our department in 1974

(7). We compared the ndings of our present study

with the study done at our institution 30 years ago.

As can be seen from Table 2, there has been no

signicant change in the mean age of patients. The

striking preponderance of male patients continues,

though less prominent. This is curious. Earlier it was

believed that the social circumstances were related

to this disparity. Those social issues have much

changed over the past 30 years and this observation

is difcult to explain and may be related to hormonal

inuence as suggested by Dyken et al (4). Zeman

and Kolar (15) mention a male to female affection

as 2.5:1 which is comparable to our study ratio of

3:1 (15). The majority of patients had myoclonus

and cognitive decline. No case of vision loss

was reported in the previous study. Hemiparesis,

Figure 4. T2 weighted MRI showing increased signal in

the parieto-occipital white matter and grey matter.

Table 2. Comparison of present and past study from

our department

Present study Singhal et al

2003 (n=32) 1974 (n=39)

n (%) n (%)

Mean age (years) 13.4 11.2

Sex (male:female) 24:8 36:3

Myoclonus 27 (84.3) 37 (94.8)

Cognitive decline 26 (81.2) 38 (97.4)

Seizures 6 (18.7) 13 (33.3)

Hemiparesis 5 (15.7) 2 (5.1)

Chorioretinitis 4 (12.5) 1 (2.5)

Vision loss 7 (21.8) 0 (0)

Early clinical features in SSPE

S V Khadilkar et al

76

choreoathetosis, tremors, and generalized seizures

were the other prominent features in the previous

study out of which choreoathetosis and tremors were

not seen in any of our patients.

Conclusions

SSPE is still an important cause of mental

decline at young ages in our set up. The mean age

of presentation has increased to 13.4 years, over

the past 30 years. A proportion of patients had

developed SSPE in spite of being vaccinated. Almost

40% of our patients presented with one or more of

uncommon features like vision loss, seizures, and

behavioral disturbances. These presentations need

emphasis in the early diagnosis of this devastating

condition.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. N.A. Mehta Shah, Professor and

Head, Department of Neurology and Dr. G.B. Daver,

Dean, Grant Medical College and Sir JJ group of

Hospitals, Mumbai for their support and allowing us

to present this work.

References

1. Dyken PR. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

Current status. Neurol Clin 1985; 3: 179-196.

2. Garg RK. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

Postgrad Med J 2002; 78: 63-70.

3. Haddad FS, Risk WS, Jabbour JT. Subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis in the Middle East: report

of 99 cases. Ann Neurol 1977; 1: 211-217.

4. Dyken PR. Neuroprogressive disease of post-

infectious origin: a review of resurging subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). Ment Retard Dev

Disabil Res Rev 2001; 7: 217-225.

5. Dyken PR, Cunningham SC, Ward LC. Changing

character of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in

the United States. Pediatr Neurol 1989; 5: 339-341.

6. Anlar B, Köse G, Gürer Y, et al. Changing

epidemiological features of subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis. Infection 2001; 29: 192-195.

7. Singhal BS, Wadia NH, Vibhakar BB, Dastur DK.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis 1-Clinical

aspects. Neurol India 1974; 22: 87-94.

8. Jin L, Beard S, Hunjan R, Brown DW, Miller E.

Characterization of measles virus strain causing

SSPE: a study of 11 cases. J Neurovirol 2002; 8: 335-

344.

9. Modlin JF, Halsey NA, Eddins DL, et al.

Epidemiology of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

J Pediatr 1979; 94: 231-236.

10. Singer C, Lang AE, Suchowersky O. Adult-onset

subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: case reports and

review of literature. Mov Disord 1997; 10: 342-353.

11. Kissani N, Ouzzani R, Belaidi H, Ouahabi H,

Chkili T. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy in subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis (report of 30 cases)

Neurophysiol Clin 2001; 31: 398-405 (in French).

12. Özturk A, Gürses C, Baykan B, Gökyiğit A, Eraksoy

M. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinical

and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of 36

patients. J Child Neurol 2002; 17: 25-29.

13. Alexander M, Singh S, Gnanamuthu C, Chandi

S, Korah IP. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis:

CT and MR imaging in a rapidly progressive case.

Neurology India 1999; 47: 304-307.

14. Brismar J, Gascon GG, von Steyern KV, Bohlega S.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: evaluation with

CT and MR. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996; 17: 761-

772.

15. Zeman W, Kolar O. Reections on etiology and

pathogenesis of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

Neurology 1968; 18: 1-7.

16. Mawrin C, Lins H, Koenig B, et al. Spatial and

temporal disease progression of adult-onset subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis. Neurology 2002; 58:

1568-1571.

17. Nakamura Y, Iinuma K, Oka E, Nihei K.

Epidemiological features of subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis from clinical data of patients

receiving a public aid for treatment. No To Hattatsu

2003; 35: 316-320 (in Japanese).

18. Schneider-Schaulies J, Meulen V, Schneider-

Schaulies S. Measles infection of the central nervous

system. J Neurovirol 2003; 9: 247-252.

19. Mgone CS, Mgone JM, Takasu T, et al. Clinical

presentation of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

in Papua New Guinea. Trop Med Int Health 2003; 8:

219-227.

20. Miki K, Komase K, Mgone CS, et al. Molecular

analysis of measles virus genome derived from SSPE

and acute measles patients in Papua, New Guinea. J

Med Virol 2002; 68: 105-112.

Early clinical features in SSPE

S V Khadilkar et al

77