Active control of turbulent boundary layer-induced sound transmission through the cavity-backed double panels

Summary (4 min read)

1. Introduction

- In high speed automotive, aerospace, and railway transportation, the turbulent boundary layer (TBL) is one of the most important sources of interior noise.

- Consequently the trim panels radiate sound into the vehicle interior.

- Between the different models developed over the years to describe the wall pressure fluctuations due to a TBL [3], the Corcos model is among the simplest [4, 5].

- The passive sound transmission control is ineffective in the lowfrequency range since the passive sound absorptive materials can not attenuate the large-length waves.

- Feedback control systems can be used instead, and some promising results have been reported in the last decade [14, 20, 21, 22].

2. The model problem

- The analytical model outlined in this section is used to predict the noise transmission through an acoustically coupled double panel system into a rectangular cavity when an active vibration isolation unit is used.

- The problem under analysis is physically given by the interaction of an aerodynamic model, that represents the TBL pressure fluctuations on the structure, and a structural-acoustic model, that gives the noise transmission and interior sound levels.

2.1. Aerodynamic model

- The wall pressure field, generated by a fully developed TBL with zero mean pressure gradient, can be regarded as homogeneous in space and stationary in time [3, 28].

- It is thus possible that the results presented in the paper qualitatively differ for different convective speeds and the dimensions of the panels.

- In the following sections the properties of the physical system used are defined in detail.

- The longitudinal and lateral decay rates of the coherences, αx and αy respectively, are normally chosen to yield good agreement with experiments.

2.2. Structural-acoustic model

- The model encompasses a cavitybacked homogeneous double panel driven on one side by a stationary TBL.

- Real sensor-actuator transducers would certainly exhibit more complex highfrequency behaviour and decrease stability margins of the active control systems considered in the study.

- In the following section, the structural-acoustic model presented describes the interaction between the vibrating structure and the turbulent flow assuming a one-way interaction, i.e. the influence of the panel vibration on the boundary layer is neglected [33].

- In Eq. (8)-(9), v represents the distribution of source volume velocity per unit volume (including the effect of the boundary surface vibration), c0, ρ0 and σac are the sound speed in air, mean density of air and acoustic damping ratio for both cavities, respectively.

3.1. Description of the simplified model

- The stability and performance analysis of the active control system are carried out using a simplified model.

- Note that the first mode of each air cavity is characterised by a uniform pressure variation throughout the cavity volume and by a zero natural frequency.

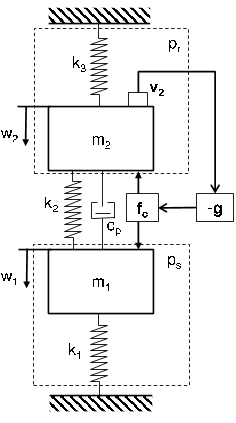

- The resulting coupled system 9 then behaves exactly as a two degree of freedom (DOF) mechanical system which, as shown in Fig. 2, is represented through mass and stiffness parameters m1,m2, k1, k2, k3, and which is characterised by two coupled mode shapes and two natural frequencies.

- The remaining geometrical and physical properties used throughout the paper are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Stability

- A system is stable if all roots of its characteristic equation have negative real parts.

- Additionally, all the principal diagonal minors ∆i of the Hurwitz matrix must be positive.

- It can be stated that in the case with β < 1 the source body, having the larger uncoupled natural frequency than the radiating body, behaves more like a fixed reference base against which the actuator can react without pronounced feedthrough effect that could otherwise compromise stability properties.

- The frequency response function between the reaction force component and the velocity sensor is thus responsible for the stability problems in case β >.

- This is because frequency response functions between two different points of a flexible structure do not necessarily have their phases bound within a 180 degree range, whereas the driving point FRFs do have their phase limited within a 180 degrees range.

3.3. Performance

- The performance of the active control system is analysed by using two different load conditions.

- Firstly, a white noise forcing is assumed on m1, Fig. 2, where the mass m1 represents the source panel and is thus referred to as the source body.

- Then, the mean squared velocity of the mass m2 is found by calculating the integral over all frequencies of the squared magnitude of the transfer mobility, Eq. (28), of the system in Fig.

- Note that the mean squared displacement of the mass m2 is proportional to the mean squared pressure in the cavity c2 according to the two mode assumption, see Eq. (29).

- The frequency- and space-averaged velocity PSD of the radiating panel is used.

3.3.1. Point force excitation

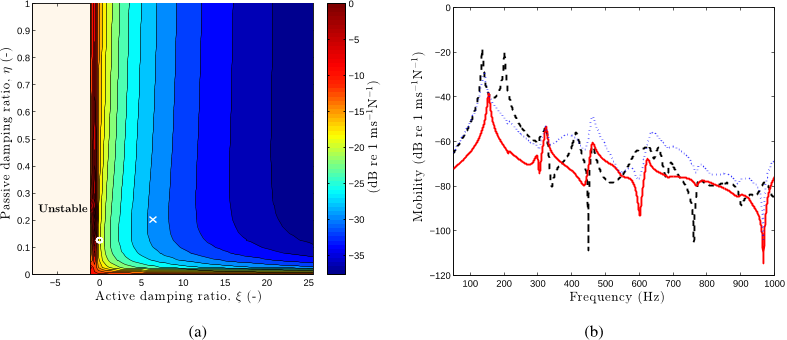

- The mean squared velocity of the radiating body is plotted as function of the passive and active damping ratio in Fig.

- This is however only due to a) the limitations of the reduced order model and its inability to capture the high-frequency behaviour of the double panel structure, and b) the fact that idealised sensor and actuator transducers are assumed.

- The passive damping ratio is again set to the optimal value that lies on the white dash-dotted line in Fig.

- In addition, the roll-off at higher dimensionless frequencies, above approximately 2.1, is compromised as shown in Fig. 5-a.

- In conclusion, the inconsistent impact of the passive damping ratio at various frequency ranges is the reason why the frequency averaged kinetic energy of the radiating panel plotted in Fig. 6-a has a minimum which corresponds to the optimal passive damping coefficient ηopt.

3.3.2. Turbulent boundary layer excitation

- The performance of the control system in reducing the TBL−induced sound transmission is studied by using the simplified, reduced order model.

- As with the point force excitation, the radiating panel kinetic energy decreases monotonically with ξ when β < 1 Fig. 7-(b) and Fig. 8-(b).

- By comparing the situation with the TBL excitation to the scenario with the white noise force excitation discussed in the previous subsection, it can be stated that the stochastic TBL pressure distribution results in a steeper high frequency roll-off of the velocity PSD, shown in Fig.

- This requires careful tuning of the passive and active damping ratios to the optimum combination.

4. Results with the full order model

- The stability and performance of the active control system are again discussed in terms of the mean squared vibration velocity of the radiating panel and the mean squared acoustic pressure in the cavity c2.

- The number of modes used enables accurate calculation of the mean squared pressure and velocity up to 1000 Hz.

- Two load conditions are analysed: 1) white noise point force excitation; and 2) TBL excitation.

- The large number of modes precludes the use of the Routh-Hurwitz criterion to assess the stability of the active system such that the Nyquist criterion is used instead.

4.1. Stability

- The sensor-actuator OL − FRF can be used to analyse the stability of the closed loop control system by using the Nyquist criterion.

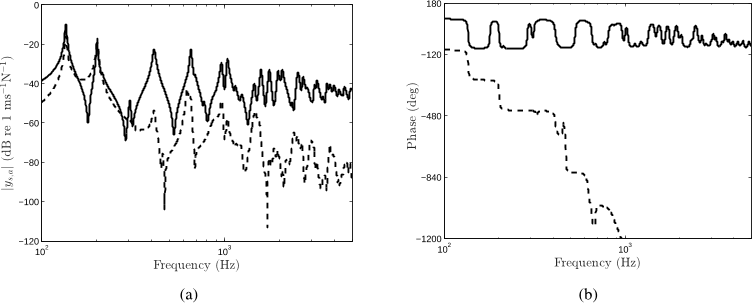

- In Fig. 11 - 12, the corresponding Bode and Nyquist plots are shown.

- Thus the system with β < 1 is unconditionally stable under the assumption of ideal sensor-actuator frequency response.

- Regarding the high-frequency behaviour, it is still interesting that the phase of the OL − FRF is bound between ±90 degrees, given the fact that the sensor and the actuator are not dual and collocated.

- Therefore the relative importance of the non-collocated FRF decreases as the frequency increases.

4.2. Performance

- In the following subsection, the performance of the control system assuming a full order model is analysed for both load conditions: point force and TBL.

- The frequency-averaged vibration velocity of the radiating panel and the sound pressure in the acoustic enclosure c2 are used as the metrics for the quality of the sound transmission control.

4.2.1. Point force excitation

- In the case of a point force excitation on the radiating panel, the mean squared velocity at the centre of the radiating panel and the mean squared acoustic pressure near the corner of 24 the cavity c2 are calculated using the procedure described in Section 2.2.

- The squared magnitude of either frequency response function is integrated numerically over the frequency range 0 − 1000 Hz.

- The amplitude of the velocity at the centre of the radiating panel per unit excitation force on the source panel is shown in Fig. 14-b, and the amplitude of the sound pressure per unit excitation force at the pressure monitoring point in the cavity c2 is shown in Fig. 15-b.

- Again, the results with the active approach are contrasted to the results using a fully passive approach.

4.2.2. Turbulent boundary layer excitation

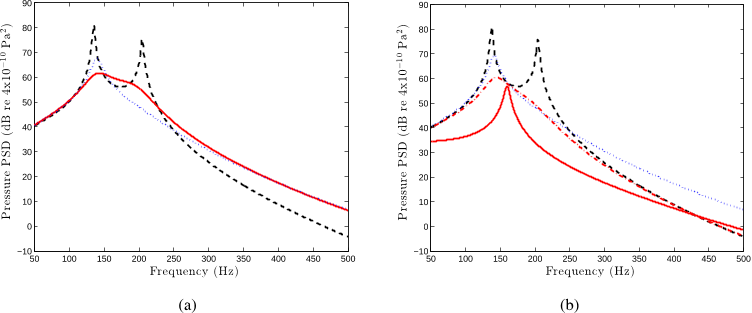

- For the full order model assuming the TBL excitation on the source panel, the performance of the control system is analysed in terms of: a) the velocity PSD at the centre of the radiating panel, pr, and b) the pressure PSD near the corner of the cavity c2, see Fig.

- The pressure PSD near the corner of c2 is plotted versus frequency in Fig. 17-b with β < 1 and Fig. 19-b with β > 1 for three cases: without control, with passive control using cp only, and finally with active control using both cp and g.

- By comparing the right-hand side plot of Fig. 16 to the right hand side plot of Fig. 17, it can be concluded that large contributions to the interior sound pressure are due to the two lowest double panel modes.

- Additional mode shapes obtained using the full order model are shown and discussed.

5. Conclusions

- The active control of TBL noise transmission through a cavity-backed double panel is investigated.

- Stability and performance of the velocity feedback active control system are carried out for a reduced order model and an increased order model.

- The theoretical analysis indicates that the first fundamental mode and the mass-air-mass mode of the coupled system are the strongest radiators of sound into the back cavity.

- Closed form expressions for these stability limits are given in terms of the minimal/maximal active damping ratio.

- The fundamental resonance frequency of the source panel is larger than the fundamental resonance frequency of the radiating panel, which results in unconditionally stable control systems such that very large feedback gains can be used.

Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

Figures (20)

Figure 1: The model problem. 5

Figure 2: Reduced order model.

Figure 13: Case for β < 1. Amplitude (a) and phase (b) of the collocated (solid line) and non-collocated (dashed line) transfer mobility.

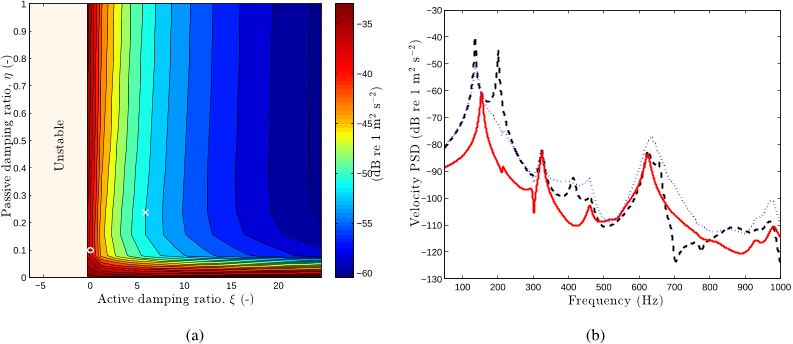

Figure 14: Mean squared velocity of the radiating panel plotted versus ξ and η in case of a point force excitation for β < 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξ = 6.3, ηopt(ξ = 6.3)) (white ×) (a). Amplitude of the velocity at the centre of pr: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·), optimal tuned active control with (ξ = 6.3, ηopt(ξ = 6.3)) (−) for β < 1 (b).

Figure 3: Principal diagonal minors plotted versus the active damping ratio ξ, (−) ∆1, (−−) ∆2, (· · ·) ∆3, (− ·−) ∆4: β > 1 (a); β < 1 (b).

Figure 8: Frequency- and space-averaged pressure PSD in the cavity c2 plotted versus ξ and η with a TBL excitation, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦): β > 1 with (ξopt , ηopt) (white ∗) (a); β < 1 with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (white ∗) (b).

Figure 7: Frequency- and space-averaged velocity PSD of the radiating body plotted versus ξ and η with a TBL excitation, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦): β > 1 with (ξopt , ηopt) (white ∗) (a); β < 1 with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (white ∗) (b).

Figure 19: Frequency-averaged pressure PSD in c2, for a TBL excitation, plotted versus ξ and η, for β > 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξopt , ηopt) (white ∗) (a). Pressure PSD for β > 1: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·); optimal tuned active control with (ξopt , ηopt) (−) (b) at (xp, yp, zp) = (Lcx/3, Lcy/3,−2Lc2z /3).

Figure 20: Stability limit for β > 1 and for different structural damping ratio: σ = 0.01 (−−), σ = 0.005 (· · ·), σ = 0.0025 (− · −) and σ = 0.0005 (−).

Figure 10: Pressure PSD in the cavity c2 for a TBL excitation: β > 1 (a); β < 1 (b). No control (−−), passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·), optimal tuned active control with (ξopt , ηopt) for β > 1 and with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (−) and (ξ = 10, η = ηopt/10) (− · −) for β < 1.

Figure 9: Velocity PSD of the radiating body for a TBL excitation: β > 1 (a); β < 1 (b). No control (−−), passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·), optimal tuned active control with (ξopt , ηopt) for β > 1 and with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (−) and (ξ = 10, η = ηopt/10) (− · −) for β < 1.

Figure D.21: Mode shapes of the full order model: 135 Hz (a); 201 Hz (b); 213 Hz (c); 304 Hz (d); 324 Hz (e); 411 Hz (f); 606 Hz (g); 630 Hz (h); 655 Hz (i). 33

Figure 5: Amplitude of the dimensionless transfer mobility of the radiating body, Eq. (35): β > 1 (a); β < 1 (b). No control (−−), passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·), optimal tuned active control with (ξopt , ηopt) for β > 1 and with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (−) and (ξ = 10, η = ηopt/10) (− · −) for β < 1.

Figure 17: Frequency-averaged pressure PSD in c2, for a TBL excitation, plotted versus ξ and η, for β < 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξ = 3.13, ηopt(ξ = 3.13)) (white ×) (a). Pressure PSD in c2 for β < 1: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·); optimal tuned active control with (ξ = 3.13, ηopt(ξ = 3.13)) (−) (b) at (xp, yp, zp) = (Lcx/3, Lcy/3,−2Lc2z /3).

Figure 18: Frequency-averaged velocity PSD at the centre of pr , for a TBL excitation, plotted versus ξ and η for β > 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξopt , ηopt) (white ∗) (a). Velocity PSD at the centre of pr , for β > 1: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·); optimal tuned active control with (ξopt , ηopt) (−) (b).

Figure 4: Mean squared velocity of the radiating body, in the non-dimensional form, Eq. (47), plotted versus ξ and η in case of a white noise excitation, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦): β > 1 with (ξopt , ηopt) (white ∗) (a); β < 1 with (ξ = 10, ηopt(ξ = 10)) (white ∗) (b).

Figure 16: Frequency-averaged velocity PSD at the centre of pr , for a TBL excitation, plotted versus ξ and η for β < 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξ = 6.3, ηopt(ξ = 6.3)) (white ×) (a). Velocity PSD at the centre of pr , for β < 1: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·); optimal tuned active control with (ξ = 6.3, ηopt(ξ = 6.3)) (−) (b).

Figure 15: Mean squared pressure in the cavity c2 plotted versus ξ and η in case of a point force excitation for β < 1, with ηopt(ξ = 0) (white ◦) and (ξ = 3.13, ηopt(ξ = 3.13)) (white ×) (a). Sound pressure in the cavity c2: no control (−−); passive control with ηopt(ξ = 0) (· · ·); optimal tuned active control with (ξ = 3.13, ηopt(ξ = 3.13)) (−) for β < 1 (b) at (xp, yp, zp) = (Lcx/3, Lcy/3,−2Lc2z /3).

Figure 11: Case for β > 1. Bode plots (a); Nyquist Plot of the open loop sensor-actuator FRF (b).

Figure 12: Case for β < 1. Bode plots (a); Nyquist Plot of the open loop sensor-actuator FRF (b).

Citations

39 citations

21 citations

Cites background from "Active control of turbulent boundar..."

...[44] presented a fully coupled analytical structural-acoustic model to study active control of turbulent boundary layer (TBL)-induced sound transmission through a cavity-backed flexible double panel....

[...]

17 citations

15 citations

9 citations

References

12 citations

"Active control of turbulent boundar..." refers background in this paper

...It should be noted that modelling the low-wavenumber region of the TBL pressure spectrum is still an active area of research [6, 7]....

[...]

11 citations

"Active control of turbulent boundar..." refers background in this paper

...Even with such integrated approach, the transmission loss of double leaf partitions is still rather poor at the frequencies below the mass-air-mass resonance [11, 12]....

[...]

9 citations

"Active control of turbulent boundar..." refers methods in this paper

...In order to model the structural-acoustic control problem at hand, the two panel displacements and the two acoustic enclosure pressures are calculated by coupling the wave equations for the two cavities with the governing equations for the two panels [35, 36]....

[...]

9 citations

8 citations

"Active control of turbulent boundar..." refers methods in this paper

...Therefore, the Corcos model is often used as a reference for other models [8, 9, 10], such as, for example, the recently developed Generalized Corcos model [7]....

[...]