This is a n Op e n Acc e s s d o c u m e n t d o w nlo a d e d fro m ORCA, C a r diff U niv e r sity's

ins tit u tion a l r e p o sito ry: h t t p s://o rc a . c a r diff.a c. uk/1 2 5 3 5 2/

This is t h e a u t h o r’s ve r sio n of a w o r k t h a t w a s s u b m i tt e d t o / a c c e p t e d fo r

p u blic a tion .

Cit a tio n fo r fin al p u blis h e d ve r sio n:

Fo r d, S h a u n a , Gilla r d, Jo n a t h a n a n d P u g h , M a t h e w 2 0 1 9. C r e a ti n g a t a x on o my

of m a t h e m a tic al e r r o r s for u n d e r g r a d u a t e m a t h e m a tic s. M S OR C on n e c tio n s

1 8 (1) , p p. 3 7-4 5. 1 0 .2 1 1 0 0/ m sor.v1 8i1 file

P u blis h e r s p a g e: h t t p s:// d oi.o r g/ 1 0. 2 1 1 0 0/ m sor.v18i1

< h t t p s:// doi.o r g/ 10 . 2 1 1 0 0/ m sor.v1 8i 1 >

Pl e a s e n o t e:

C h a n g e s m a d e a s a r e s ul t of p u bli s hin g p r oc e s s e s s u c h a s c o py-e di tin g,

for m a t tin g a n d p a g e n u m b e r s m a y n o t b e r efle ct e d in t his ve rsio n. Fo r t h e

d efinitiv e ve r sio n of t hi s p u blic a tio n, pl e a s e r ef e r t o t h e p u blis h e d s o u r c e . You

a r e a d vis e d to c o ns ult t h e p u blis h e r’s v e r sion if yo u wi s h t o cit e t his p a p er.

This ve r sio n is b ein g m a d e av ail a bl e in a c co r d a n c e wit h p u blis h e r p olicie s.

S e e

h t t p://or c a.cf. ac. uk/ polici es. ht m l fo r u s a g e p olici es. Co py ri g ht a n d m o r al ri g h t s

for p u blica tio n s m a d e a v ail a ble in ORCA a r e r e t ai n e d by t h e co py ri g h t

h old e r s.

MSOR Connections 18(1) – journals.gre.ac.uk 37

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Creating a Taxonomy of Mathematical Errors for

Undergraduate Mathematics

Shauna Ford, School of Mathematics, Cardiff University, UK. Email: FordS6@cardiff.ac.uk.

Jonathan Gillard, School of Mathematics, Cardiff University, UK. Email: GillardJW@cardiff.ac.uk.

Mathew Pugh, School of Mathematics, Cardiff University, UK. Email: PughMJ@cardiff.ac.uk.

Abstract

In this paper we develop a taxonomy of errors which undergraduate mathematics students may

make when tackling mathematical problems. We believe that a taxonomy would be useful for staff

in giving feedback to students, and would facilitate students’ higher-level understanding of the types

of errors that they could make.

Keywords: assessment, feedback, errors.

1. Introduction

There has been a considerable amount of research over the last century into mathematical errors

(Radatz, 1980). Typically this research is in the context of learning mathematics in school (e.g.

Radatz, 1980; Matz, 1982; Kieran, et al., 1990; Foster, 2007). Such studies tend to focus therefore

on errors which are either arithmetic or algebraic in nature, such as errors in long division, or

misinterpreting as . An approach which seems to receive particular attention in the

U.S. is error analysis (e.g. Ashlock, 2010; Idris, 2011). In this approach pupils’ errors are

systematically recorded by the teacher, and analysed for patterns so that teacher can then plan what

potential remedial action will be necessary to correct any underlying misconceptions.

Whilst research into errors made by pupils in a school context can be of benefit to teachers in higher

education, the contexts are also very different. School pupils will possess a wide range of

mathematical abilities, and many will have a dislike or even fear of mathematics. On the other hand

mathematics undergraduate students possess a strong mathematical ability and have chosen to

study the subject further. Thus one would hope that many of the errors made by pupils, resulting

from a misunderstanding of even basic concepts within mathematics, would not be made by

mathematics undergraduates. The approach to mathematics also tends to be very different in the

two contexts. In school the focus is almost exclusively on algorithms to solve problems, whilst

undergraduate mathematics will also focus on understanding concepts and proving results.

Therefore the types of error made in higher education will typically be of a different nature to those

in primary or secondary education.

Much of the above research, as well as more general studies on mathematical errors, focuses on

understanding the underlying cognitive causes of these errors, either in order to understand the

cause of specific errors, or more generally to identify the mechanisms underlying these errors. It is

argued that most mathematical errors are causally determined, and very often systematic (Radatz,

1980). Radatz (1979) identified five error categories: (1) errors due to language difficulties, (2) errors

due to difficulties in obtaining spatial information, (3) errors due to deficient mastery of prerequisite

skills, facts, and concepts, (4) errors due to incorrect associations or rigidity of thinking, and (5) errors

due to the application of irrelevant rules or strategies. Ben-Zeev (1998) constructed a taxonomy of

mathematical errors and attempted to identify the causes of these errors by integrating findings from

different studies. The focus in this and other research is to understand why a student makes an error.

For example, a student may over-generalize an algorithm which holds in one context to a structurally

38 MSOR Connections 18(1) – journals.gre.ac.uk

similar context where the algorithm no longer works, something Ben-Zeev calls syntactic induction

(Ben-Zeev, 1998).

It will often however be difficult, if not impossible, to diagnose the underlying error in a student’s

reasoning or understanding solely from the student’s written solution to a problem. Therefore this

paper will not focus on this, but rather on classifying the particular types of errors students make

when attempting to solve mathematical problems. Such a classification should provide enough

details so that a student can identify what it is they have done wrong, whilst keeping the number of

classes as small as possible. We believe that creating a taxonomy of errors is useful for the following

reasons:

it will be a useful resource for students to see which errors to avoid, some of which may not

have been appreciated previously;

it could be incorporated into a feedback tool for lecturers to enrich the feedback offered to

students;

it would allow for the consideration of relationships between different types of error.

Whilst this paper implicitly assumes that the students we consider are undergraduate mathematics

students, the developments in this paper could also be applied to GCSE or A-level mathematics

students.

This work was undertaken as part of an undergraduate summer project by the first author. The paper

is structured as follows. In section 2 we consider the definition of error that we use in this paper, and

what causes errors to take place, before relating this information to errors in mathematics. The

taxonomy is given in section 3.

2. Human Error

Human error is a failure of a planned action to achieve a desired outcome. Errors can be made in

one of two ways – either the plan itself may be inadequate, or else the execution of that plan may

include actions that are unintentional and which do not lead to the desired outcome, as illustrated in

figure 1.

Figure 2. Occurrence of Human Errors.

Failures in planning are often referred to as mistakes rather than errors. There are two types of

mistakes: knowledge-based and rule-based (Reason, 1990). Knowledge-based mistakes occur

when an individual has an inability to reach an end goal because of a lack of knowledge. Rule-based

mistakes occur when an individual wrongly modifies an established process. Such mistakes are more

. Plan

1

. Action

2

Desired

Outcome

Adequate

Adequate

Inadequate

Unintentional

Intentional

Intentional

Error

Success

Error

3

. Outcome

MSOR Connections 18(1) – journals.gre.ac.uk 39

likely to go unnoticed when the outcome is not specifically known. The modification is likely to be

informed by previous successful experiences (Rasmussen, 1986, p.102). Rule-based mistakes fall

into two categories:

• Misapplication of a good rule: Occurs when an individual applies a rule which may be

perfectly adequate in another situation, but which may not meet the conditions and demands

of the problem being considered (Reason, 1990, p.75). Such errors are more likely to occur

when an individual has applied the rule successfully for a previous problem.

• Application of a bad rule: A good rule may become bad following changes that an individual

makes that are not thoroughly considered. This may be from the alterations not being

managed appropriately, or the creation of a bad rule from incorrect knowledge. This can

appear on varying levels; the rule could be entirely wrong, the rule may be clumsy or

inefficient but still achieve the desired outcome, or the rule could be inadvisable since whilst

leading to a good approximate solution, repeated use may worsen this approximation.

Unintentional actions are classed as skill-based errors. These often occur when implementing

elementary or standard procedures, due to a lack of consciousness or control (Rasmussen, 1986,

p.100). Skill-based errors fall into two categories: memory lapses and slips of actions.

• Memory lapse: These errors include losing place in a sequence of steps, forgetting to do

something, or forgetting the overall plan entirely.

• Slip of action: An unintentional action that occurs at the point of execution. This error is often

caused by a process being performed subconsciously, skipping or reordering steps in a

procedure, or experiencing a distraction.

The skill-rule-knowledge framework described above only offers a partial account of possible deviant

behaviour (Reason, 1990). Humans plan and execute their actions in social environments that may

affect their performance. Whilst mistakes and skill based errors are defined as errors made in the

individual’s cognitive stages, their behaviour may also be altered by the situation’s social context.

Violations are deliberate alterations considered necessary by the individual to adjust to external

influences (Reason, 1990, p.195). Hence the violator is not always entirely blameworthy for the

decision made. The following three types of violation are distinguished:

• Routine violations: These occur due to natural instinct to take the process that requires the

least amount of effort. This becomes habitual and forms a set pattern of errors in their

behaviour.

• Situational violations: An individual alters their behaviour due to a change in their social

surroundings. These changes can include excessive time pressure, stress, workplace

design, and inadequate or inappropriate equipment.

• Exceptional violations: These occur when an individual adopts a cause of action known to be

usually incorrect but determines that the current situation is an exception.

Violations and errors from the previous skill-rule-knowledge framework can coincide or appear alone.

The classification of human errors described above is illustrated in figure 2.

40 MSOR Connections 18(1) – journals.gre.ac.uk

Figure 2. Human Error Types.

How might these types of errors appear in the context of a student attempting a mathematics

problem? Suppose a student was answering the question:

Differentiate the function .

This requires using the product and chain rules to obtain an answer of . A ‘slip

of action’ might be manifested as a numerical slip-up (such as writing the coefficient of the derivative

as 5 rather than 6, possibly through subconsciously confusing with ), or a careless

error in writing the solution (such as writing by mistake). If the student could not recall the chain

rule then this would be a ‘memory lapse’, whereas if they did not know the chain rule then they would

likely make a ‘knowledge-based’ error. If they had incorrectly recalled the chain rule, then the error

would be an ‘application of a bad rule’. On the other hand, if the student had (wrongly) integrated the

function correctly, they are likely to be guilty of ‘misapplication of a good rule’. A ‘routine violation’

could occur if a student had made the same error often enough so that they no longer realised it was

an error, for example, writing for the derivative of . A ‘situational violation’ might be more

likely if the student had to answer this question in an examination, perhaps due to the stress and

time-pressures of the situation. An ‘exceptional violation’ may occur if a student is presented with the

question ‘Show that the derivative of is given by ’, where

they might ‘violate’ a rule in a desperate attempt to arrive at a solution which matches the given

answer.

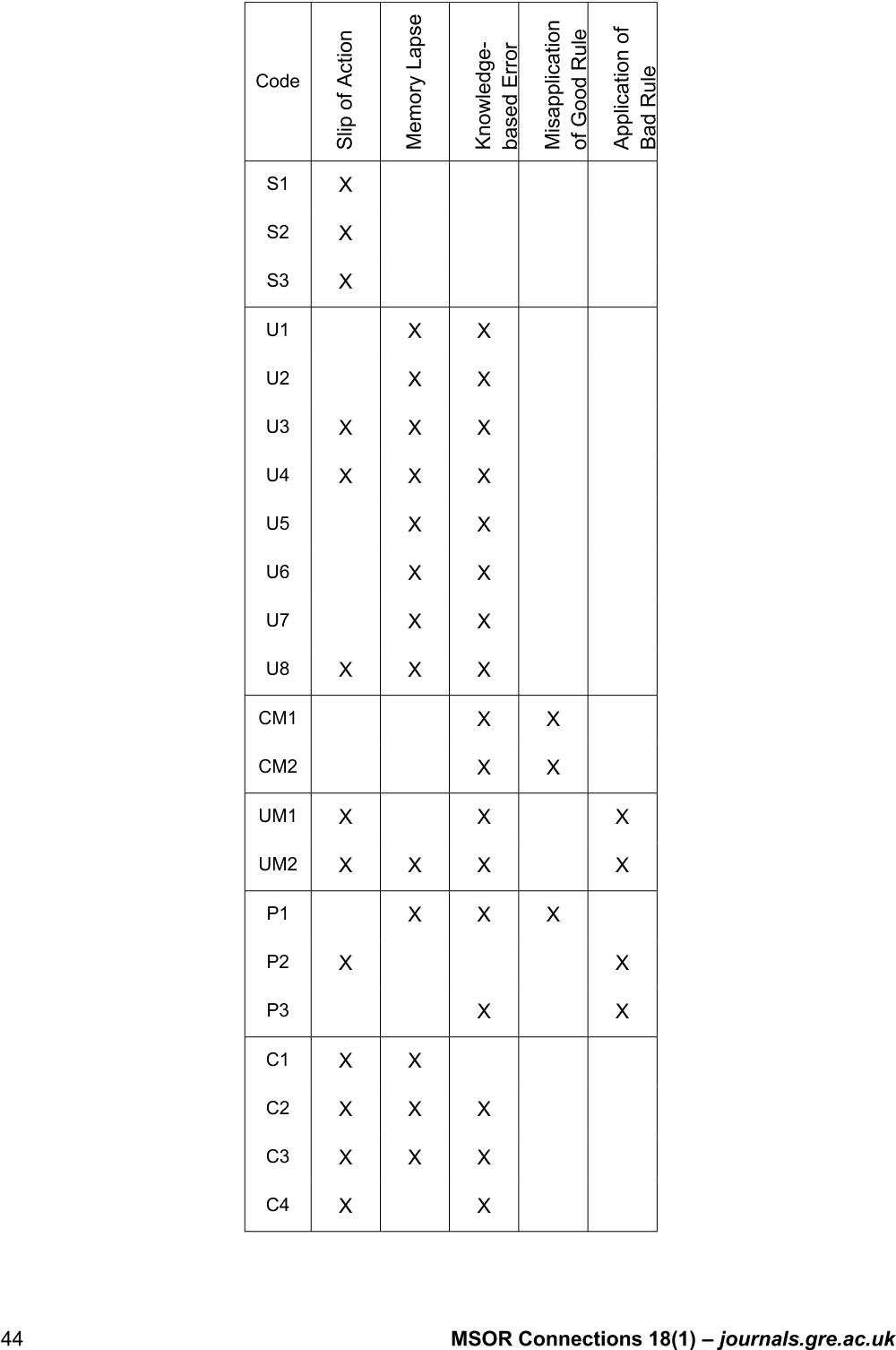

3. Creating a Taxonomy of Mathematical Errors

A taxonomy is the “theoretical study of classification, including its bases, principles, procedures and

rules” (Simpson, 1961, p.11). It is a way of classifying entities verifiable by observation (Bailey, 1994,

p.6). A successful taxonomy will provide classes that are both exhaustive (an appropriate class for

each entity) and mutually exclusive (only one suitable class for each entity) (Bailey, 1994, p.3).

Human Error

Skill-based Error

Mistake

Violation

Situational

Exceptional

Routine

Slip of

Action

Memory

Lapse

Knowledge-

based

Rule-based

Misapplication

of a good rule

Application

of a bad rule