Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

2,818 citations

1,139 citations

902 citations

809 citations

760 citations

12,469 citations

11,095 citations

...Non-tariff barriers (NTBs) were reduced from 87 percent in 1987 to 45 percent in 1994 (Topalova (2007))....

[...]

...This result confirms the importance of the new variety margin during a trade reform emphasized in Romer (1994). We re-run regression (7) for the intermediate and final goods sectors in columns 2 and 3 of each panel, respectively. Consistent with the evidence in Table 1, the relationship between tariff declines and the extensive margin is particularly pronounced for intermediate products. The results indicate that coefficient on tariffs for the intermediate sectors in column 2 is more than twice as large as the tariff coefficient for the final goods sectors. Moreover, while the results for intermediate products are also robust to the alternative definitions of a variety used in panels B and C, the results for final products are more sensitive across different variety definitions.(15) Our results are generally consistent with the evidence in Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare (1997) and Arkolakis et al (2008), who also find that the range of imported varieties expands as a result of the tariff declines in Costa Rica....

[...]

...First, endogenous growth models, such as the ones developed by Romer (1987, 1990) and Rivera-Batiz and Romer (1991), emphasize the static and dynamic gains arising from the import of new varieties....

[...]

...Several theoretical papers have emphasized the importance of intermediate inputs for productivity growth [e.g., Ethier (1979, 1982), Markusen (1989), Romer (1987, 1990), Grossman and Helpman (1991)]....

[...]

...This result confirms the importance of the new variety margin during a trade reform emphasized in Romer (1994). We re-run regression (7) for the intermediate and final goods sectors in columns 2 and 3 of each panel, respectively. Consistent with the evidence in Table 1, the relationship between tariff declines and the extensive margin is particularly pronounced for intermediate products. The results indicate that coefficient on tariffs for the intermediate sectors in column 2 is more than twice as large as the tariff coefficient for the final goods sectors. Moreover, while the results for intermediate products are also robust to the alternative definitions of a variety used in panels B and C, the results for final products are more sensitive across different variety definitions.(15) Our results are generally consistent with the evidence in Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare (1997) and Arkolakis et al (2008), who also find that the range of imported varieties expands as a result of the tariff declines in Costa Rica. However, there is one important difference. In India, Table 1 indicates that new imported intermediate varieties accounted for a sizable share of total imports. In contrast, in Costa Rica, newly imported varieties accounted for a small share of total imports and thus generate relatively small gains from trade (Arkolakis et. al (2008))....

[...]

9,036 citations

6,911 citations

...Several theoretical papers have emphasized the importance of intermediate inputs for productivity growth [e.g., Ethier (1979, 1982), Markusen (1989), Romer (1987, 1990), Grossman and Helpman (1991)]....

[...]

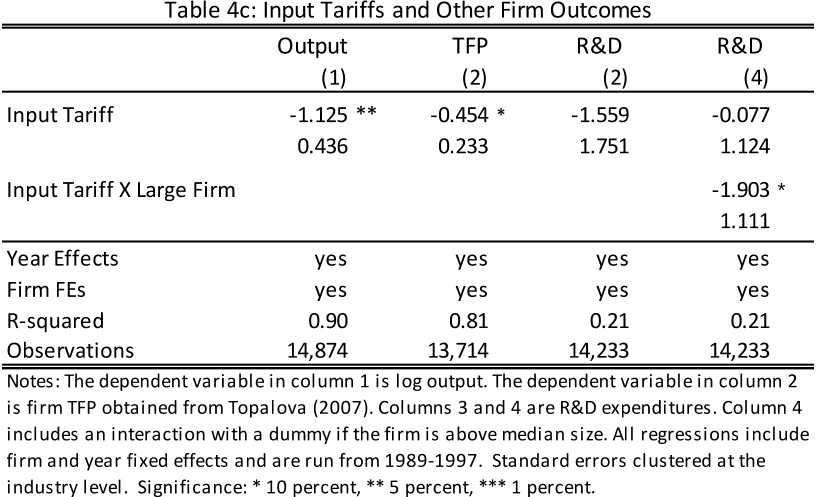

...…(column 3).20 This evidence is consistent with predictions of theoretical papers that have emphasized the importance of intermediate inputs for productivity growth [e.g., Ethier (1979, 1982), Markusen (1989), Romer (1987, 1990), Rivera-Batiz and Romer (1991), and Grossman and Helpman (1991)]....

[...]

4,380 citations

...The presence of multiproduct firms further complicates the interpretation of TFP obtained from Olley and Pakes (1996) methodology [see De Loecker (2007)]....

[...]

More detailed data would enable us, for example, to study the determinants and consequences of differential adoption of imported inputs by Indian firms, although such a study would need to address the endogeneity of this differential adoption of imported inputs by firms – the trade policy changes the authors exploit as a source of identification do not vary by firm. In future work the authors plan to further explore the contribution of these new products to TFP by exploiting product-level information on prices and sales available in their data. While the authors do not concentrate on aggregate growth, the fact that the creation of new domestic products accounted for nearly 25 percent of total Indian manufacturing output growth during their sample period suggests that the implications of access to new imported intermediate products for growth are potentially important. This will allow us to ultimately provide a direct estimate of the dynamic gains from trade.

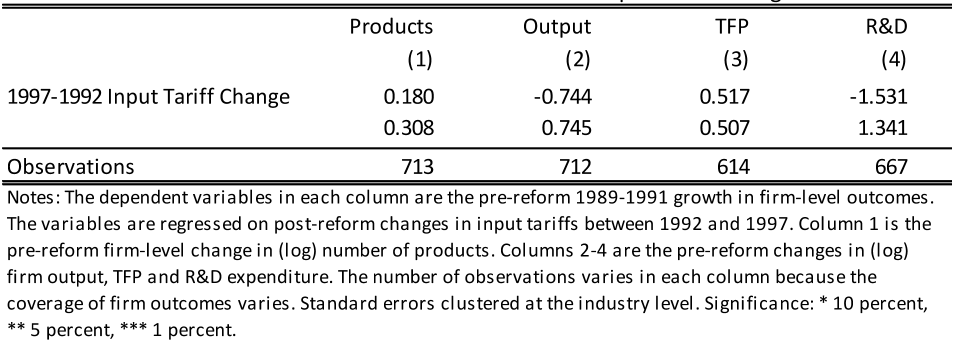

Perhaps the most controversial component of this identification strategy is that the unobservable components in (19) include total factor productivity since there is a evidence that trade liberalizations lead to productivity improvements.

production process by domestic firms, the observed declines in unit values of existing products will lower the marginal cost of production for Indian firms.

One would expect elimination of x-inefficiency to be driven by pro-competitive output tariffs, rather than changes in input tariffs.

During the period of their analysis, input tariffs declined on average by 24 percentage points, andfrom column 2, the decline in input tariffs led to a .25% decline in input variety index on average.

The coefficient on the input variety index in column 2 is negative and statistically significant suggesting that an increase in input variety (captured by a lower index number) is associated with an expansion of firm scope.

While the authors do not concentrate on aggregate growth, the fact that the creation of new domestic products accounted for nearly 25 percent of total Indian manufacturing output growth during their sample period suggests that the implications of access to new imported intermediate products for growth are potentially important.

The relationship is also economically significant: lower input tariffs account on average for 31 percent of the observed increase in firms' product scope over this period.