1

Intergenerational Persistence in Income and Social Class:

The Impact of Within-Group Inequality

Jo Blanden*, Paul Gregg** and Lindsey Macmillan**

March 2012

* Department of Economics, University of Surrey and Centre for Economic

Performance, London School of Economics

** Department of Economics, University of Bristol and Centre for Market and

Public Organisation, University of Bristol

Abstract

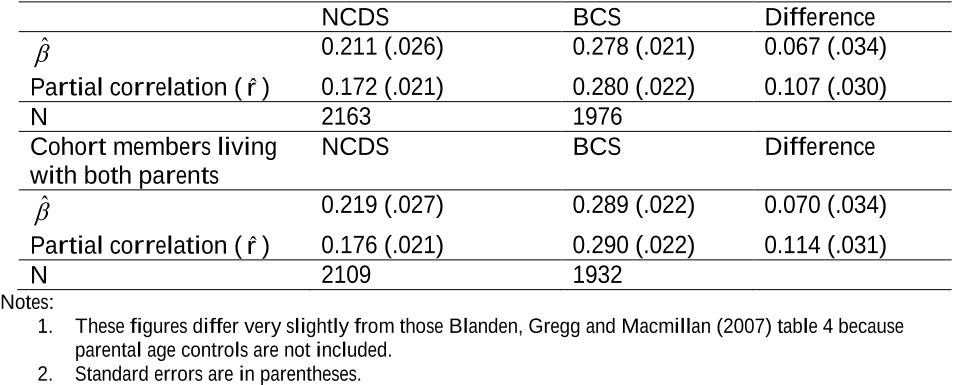

Family income is found to be more closely related to sons’ earnings for a cohort born in 1970

compared to one born in 1958. This result is in stark contrast to the finding on the basis of

social class; intergenerational mobility for this outcome is found to be unchanged. Our aim

here is to explore the reason for this divergence. We derive a formal framework which relates

mobility as measured by family income/earnings to mobility as measured by social class.

Building on this framework we then test a number of alternative hypotheses to explain the

difference between the trends. We find evidence of an increase in the intergenerational

persistence of the permanent component of income that is unrelated to social class. We reject

the hypothesis that the observed decline in income mobility is a consequence of the poor

measurement of permanent family income in the 1958 cohort.

JEL codes: J13, J31, Z13

Keywords: Intergenerational income mobility, social class fluidity, income inequality.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Anders Björklund, Stephen Machin, Sandra McNally, Elizabeth

Washbrook, Christian Dustmann, Patrick Sturgis, Robert Erikson and John Goldthorpe for

their helpful comments. We also appreciate the comments of the editors and referees who

have helped to substantially improve the paper.

2

1. Introduction

Both economists and sociologists measure the intergenerational persistence of socio-

economic status, with economists tending to use income or earnings as the measure of status

(for surveys see Solon, 1999, Black and Devereux, 2010) while sociologists use fathers’

social class (Erikson and Goldthorpe, 1992) or an index of occupational status (Blau and

Duncan, 1967). To ascertain whether the measured extent of mobility is high or low, both

literatures have asked: i) how does mobility compare across nations? ii) has mobility

increased or decreased across time? For both of these comparisons the findings of economists

and sociologists contrast sharply for the UK.

International comparisons of income mobility place the UK as a country with low

mobility (Corak, 2006) whereas those using the measure of social class/occupational status

tend to rank it closer to the middle (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992, Breen, 2004). Cross-

country rankings across the two approaches are very weakly correlated with each other

(Blanden, 2011). Similar ambiguity exists when comparing trends in intergenerational

mobility across time. Blanden, Goodman, Gregg and Machin (2004) find that

intergenerational income mobility decreases for a cohort born in 1970 (British Cohort Study)

compared to a cohort born in 1958 (National Child Development Study) while Goldthorpe

and Jackson (2007) find no change in social class mobility for the same datasets. Our aim in

this research is to analyse the factors responsible for the difference in the measured trends in

mobility. Our interest in trends is driven, in part, by wide acceptance of the finding of falling

mobility among politicians and commentators and its contribution to the sense that Britain

has a ‘mobility problem’ (Goldthorpe and Jackson, 2007, Blanden, 2010 and Saunders,

2010). It is therefore crucial to examine the robustness of this result given the contrary results

emanating from the literature that uses social class as the relevant measure.

In addition, we aim to draw out the conceptual links between mobility as measured by

economists and sociologists and therefore offer a fresh perspective on both literatures. The

divergent results may simply reflect underlying conceptual differences. Economists are

aiming to measure economic resources whereas class reflects workplace autonomy and

broader social capital (Goldthorpe, 2000). However, the view we adopt here is that both

approaches are trying to assess long-term or permanent socio-economic status but measure it

in different ways. In principle there are advantages and disadvantages to both measurement

approaches. Erikson and Goldthorpe use a seven-category class schema, and might therefore

only capture a limited amount of the potential variation in permanent economic status

between families (see critiques by Grusky and Weeden 2001 and McIntosh and Munk 2009).

3

In addition, mobility measures based on fathers’ social class or fathers’ earnings will ignore

the contribution of mothers. Recently economists have moved to using measures of parental

income in the first generation to account for this increasingly important contribution (Lee and

Solon, 2009, Aaronson and Mazumder, 2008). However, social class measures are sometimes

argued to be better at measuring the most important aspects of the permanent status of the

family (see Goldthorpe and McKnight, 2006). A particular difficulty with the income data

that we use from the cohort studies is that it is measured based on a single interview where

families are asked about their current income. Erikson and Goldthorpe (2010) and Saunders

(2010) suggest that social class is a more reliable measure than current income and that the

differing results between the two approaches are explicable by the poor measurement of

family income in the 1958 cohort.

We begin our analysis by formulating a framework to examine the relationship

between permanent income, social class and current income. This framework is then explored

empirically using the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). We find that there is a

substantial portion of permanent income which is unrelated to social class. Conceptually, this

component can account for the divergent results. Section 3 of the paper outlines the main

results concerning the trend in mobility over the British cohorts using both economic and

sociological methodologies and addresses the main issues concerning data and measurement.

We focus on a number of specific measurement issues in the National Child Development

Study (NCDS) which might explain our result that income mobility is greater in the earlier

cohort compared with the later British Cohort Study (BCS). We find no evidence to support

the hypothesis that data quality or differential measurement is generating the observed

decline in mobility.

In Section 4 we detail other potential mechanisms that could generate different trends

in measured income and social class mobility. To do this we show that current income can be

decomposed into a number of different components. As mentioned above, the permanent

component can be split into the part associated with social class, and the residual part, which

we refer to as within-class permanent income. In addition current measured income will

include transitory error (the difference between current and permanent income) and finally

any mismeasurement. We then establish four alternative testable hypotheses that could

account for the diverging trends in mobility. In brief they are as follows: (1) the link between

fathers’ social class and family income within generations has changed, perhaps due to the

increasing role of women in accounting for family socio-economic position; (2) the

4

divergence is due to differential measurement error across the cohorts; (3) within-class

permanent income has become more important in determining children’s outcomes; and (4)

differences can be explained by a decline in the transitory component of parental income.

We find no evidence that a change in the mapping from father’s social class to income

affects our results; instead we find that a substantial part of the increased persistence across

generations can be predicted by observable short and long-run income proxies. Indeed, it is

possible to plausibly account for the full rise in income persistence through the increased

persistence of within-class permanent income. This is fully consistent with the data

examination which finds no evidence that the differential results could be explained by

measurement problems. In summary, it appears that explanation (3) above, is the most likely.

2. Measuring permanent income

2.1 The components of income

Here we set out a framework which demonstrates the relationships between permanent family

income, income at a point in time and fathers’ social class. This provides clear foundations

for our examination of the reasons behind the divergent results regarding intergenerational

mobility as measured by income or social class.

For economists, the intergenerational relationship of interest is the relationship

between parents’ permanent income and the child’s permanent income. y* represents the log

of permanent income with subscripts p and s referring to the parents and child

(son).Intergenerational mobility can be summarised by

ˆ

,

the estimate of the coefficient

from the following equation:

**

si pi i

y y u

(1)

The focus on sons here simplifies the analysis so that we are focusing on male social class in

both generations and to reduce the issues resulting from endogenous labour market

participation (a lot more important for women). Note that we are considering an asymmetric

relationship, relating combined parental income to the sons’ own earnings. We take care to

reflect this asymmetry in the rest of the paper and we explicitly consider the role of mothers’

earnings as part of our first hypothesis in Section 4 below.

The intergenerational correlation, r, is also of interest in cross-cohort studies as this

adjusts

for any changes in variance that occur across cohorts.

ˆ

r

is calculated by adjusting

ˆ

by the sample standard deviations of parental income and child’s income. Björklund and

5

Jäntti (2009) urge the more widespread use of this statistic when making international

comparisons of mobility and the same arguments apply when considering trends over time.

)

ˆ

(

)

ˆ

(

ˆ

ˆ

*

*

s

p

y

y

r

(2)

Following Björklund and Jäntti (2000), permanent parental income can be

decomposed into the part that is associated with fathers’ social class (in our exposition social

class is denoted by a continuous variable

fi

SC

, but categorical variables are used in our

analysis; the subscript f represents father) and

p

v

.

p

v

is the parents’ permanent income that is

uncorrelated with fathers’ social class.

*

pi p fi pi

y SC v

(3)

p

will reflect the relationships with fathers’ social class and of all the different components

which make up total income: fathers’ and mothers’ earnings and unearned income. This is a

point we shall return to later. The child’s permanent income can also be split into similar

components: the part that is related to the child’s own class and the part that is independent of

this.

*

si s si si

y SC v

(4)

Unfortunately, permanent income is generally not available for intergenerational research

(see Solon, 1992 for the first discussion of resulting biases) and the British cohort studies

suffer from this limitation. Measured current parental income is permanent income plus the

deviation between current measured income and permanent income (

pi

e

). Later in the

analysis we will explore the components that make up this term, but for now we consider it to

be anything which leads to a difference between measured and permanent income. Measures

of current income are related to these components as follows:

pipifippi

evSCy

(5)

sisisissi

evSCy

(6)

Under classical measurement error assumptions that the level of measured

i

y

is uncorrelated

with the size of the total error and that errors are uncorrelated across generations it is

straightforward to show that any error in measuring parental permanent income will lead to a