Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

344 citations

...Blanden et al. (2010a) make a similar argument about the relationship between social class fluidity and income mobility in the UK; asserting that the transmission of income inequality within classes is essential to explaining why the UK has become more immobile on the basis of income at the same…...

[...]

...We use the comparable data sets generated for Blanden et al. (2010b) which examine the relationship between sons’ earnings and total parental income, and merge in information on fathers’ and sons’ education in years and class for both generations (see notes to Table 6 for more details)....

[...]

...Blanden et al. (2010b) report a lower estimate of intergenerational income mobility for the USA, based on slightly different sample selection decisions....

[...]

332 citations

273 citations

264 citations

242 citations

196 citations

193 citations

...This confirms the findings of Blanden et al. (2004), Goldthorpe and Jackson (2007) and Erikson and Goldthorpe (2010)....

[...]

...Our interest in trends is driven, in part, by wide acceptance of the finding of falling mobility among politicians and commentators and its contribution to the sense that Britain has a ‘mobility problem’ (Goldthorpe and Jackson, 2007; Blanden, 2010; Saunders, 2010)....

[...]

...We follow Goldthorpe and Jackson (2007) in creating our measures....

[...]

...E-mail: lindsey.macmillan@bristol.ac.uk across the two approaches are very weakly correlated with each other (Blanden, 2011)....

[...]

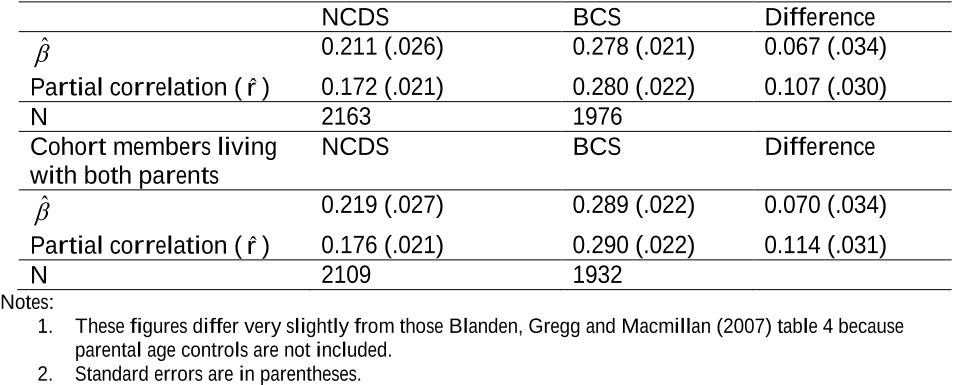

...…(2004) found that intergenerational income mobility decreases for a cohort born in 1970 (British Cohort Study (BCS)) compared with a cohort born in 1958 (National Child Development Study (NCDS)) whereas Goldthorpe and Jackson (2007) found no change in social class mobility for the same data sets....

[...]

186 citations

186 citations

180 citations