Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

2 citations

1,534 citations

[...]

1,426 citations

1,410 citations

548 citations

525 citations

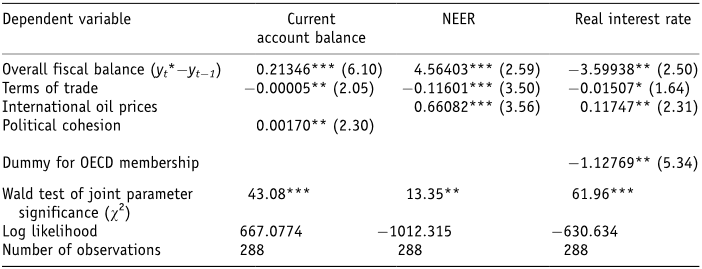

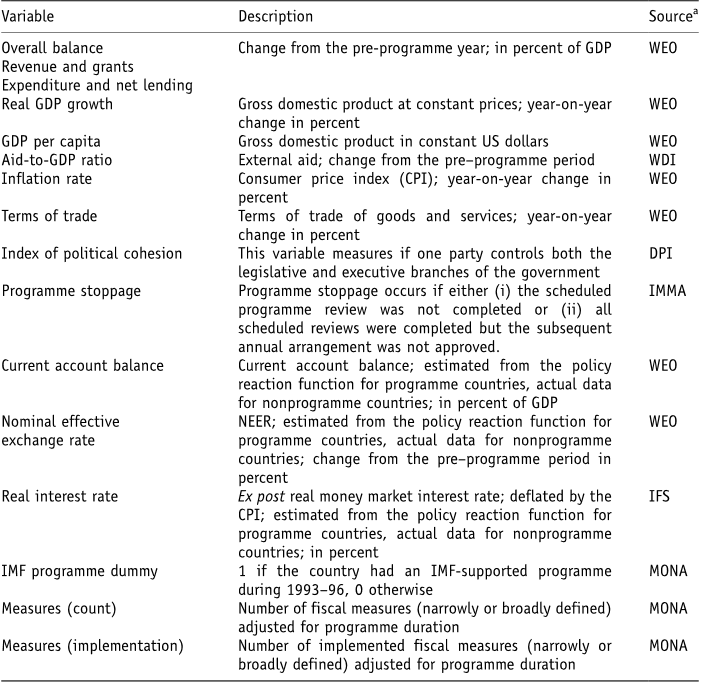

The findings in this paper are not definitive and the possibilities for further research are extensive. Second, the policy reaction function can be specified differently, reflecting, for example, policies that would stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio or that would be based on ‘ fiscal rules ’.

Regarding the former, strong special interests, political instability, inefficient bureaucracies, lack of political cohesion, and ethno-linguistic divisions weakened programme implementation.

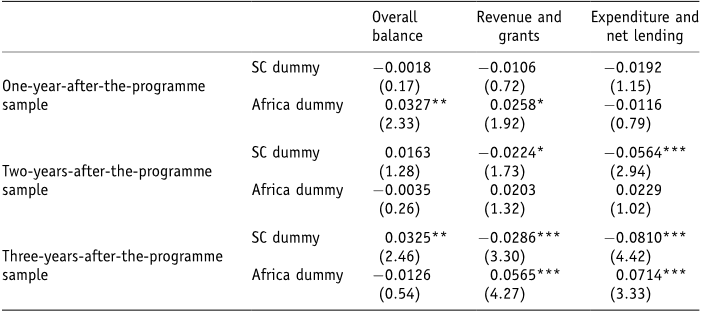

in IMF-supported programmes that included structural conditions, the adjustment was effected primarily through sharp expenditure compression in order to offset revenue declines.

Fp rog ram me d u mm ya0 .01 3 8(0 .88 )0 .01 0 7(0 .67 )0 .01 8 0(0 .85 )Co n diti ona li tyva ri able sSt ruct u ral con d itio n alit y(d u mm y)b0 .04 0 7(3 .10 )0 .03 8 9(3 .19 )0 .03 6 8(3 .20 )0 .03 2 4(4 .01 )0 .06 2 0(4 .49 )0 .04 9 7(4 .12 )R 20 .45 40 .44 90 .50 50 .47 00 .31 90 .32 20 .37 10 .33 70 .44 80 .45 20 .53 40 .50 3Lo g -lik elih o o d1 7 6 .81 7 6 .31 8 2 .31 7 8 .41 6 6 .71 6 6 .91 7 1 .11 6 8 .21 4 4 .11 4 4 .61 5 2 .51 4 9 .3N u mb ero fo b serv atio n s1 1 21 1 21 1 21 1 21 0 91 0 91 0 91 0 99 79 79 79 7N o rmal ity test [w2 (2,2 )]1 6 .41 2 4 .12 9 .26 2 2 .82 2 6 .83 2 5 .54 2 3 .63 2 3 .22 2 1 .23 1 6 .34 1 8 .94 2 6 .62H eter o sced asti city test (F) 1 .36 1 .05 1 .02 1 .55 0 .52 0 .77 0 .64 0 .96 0 .72 1 .48 0 .92 0 .39

The structural conditionality variables were negative and significant, suggesting relative expenditure compression in countries with a structural conditionality of 2 percentage points of GDP or more.

The fiscal balance improved in two-thirds of all countries by an average of 2 percentage points of GDP between the pre-programme and post-programme periods or between 1993 and 1999 for the nonprogramme countries (Figure 1 and Table 2).

post–programme fiscal performance in those countries was driven by accelerating expenditure compression, which may not be a bad thing, provided, for example, the pre–programme level of spending was wasteful or that a statist budget was replaced with a less intrusive one.

An appropriate technique is the general evaluation estimator (GEE), due to Goldstein and Montiel (1986), which constructs counterfactual economic policies first and then tests the importance of IMF-supported programmes.

15 Gupta et al. (2002) reported that the probability of a reversal in fiscal adjustment was as high as 70 percent at the end of the second post-programme year for low-income countries.

Providing the macroeconomic programme remained on track, the missed condition would likely be waived, the likelihood of waivers being positively related to the political clout of individual countries (Bird, 2002).

The magnitude of the post–programme fiscal improvement was not uniform, however, and nonprogramme countries improved their fiscal balances by more than programme countries: 3 and 12 of a percentage points of GDP, respectively.

the nature of the initial disequilibrium differed across countries: in nonstructural programme countries, GDP declined more sharply prior to the programme and their rates of inflation and GDP per capita were higher (Table 3).