Latin America in the rearview mirror

TL;DR: This paper found that Latin American countries are the only Western countries that are poor and that are not gaining ground on the U.S. due to TFP differences, and that this failure is not plausibly accounted for by human capital differences, but rather reflects inefficient production.

About: This article is published in Journal of Monetary Economics.The article was published on 2005-01-01 and is currently open access. It has received 179 citations till now. The article focuses on the topics: Latin Americans & Total factor productivity.

Summary (5 min read)

Jump to: [1. Introduction] – [2. A Neoclassical Framework] – [3. Latin America's Persistent Economic Stagnation] – [5. Human Capital Is Not a Major Factor] – [6. Latin American Stagnation and Competitive Barriers] – [7. Latin America Puts Up Significant Competitive Barriers] – [B. Latin America's Domestic Competitive Barriers: High Entry Barriers] – [8. Microeconomic Evidence on the Impact of Competition] – [A. Eliminating Competition in the Venezuelan Oil Industry] – [B. Eliminating Competition in the Venezuelan Iron Industry] – [C. Allowing Entry in Chile's Copper Industry] – [D. Reversing Quotas in Brazil's Computer Industry] – [E. Privatizing State-Owned Enterprises: Brazilian Iron Ore] – [F. The Large-Scale Privatization of Mexican SOEs] – [G. The Large-Scale Privatization of Argentinian SOEs] and [9. Conclusion]

1. Introduction

- Various short-run crises-exchange rate crises, debt crises, inflation crises, balanceof-payment crises, financial crises-have dominated recent macroeconomic research about Latin America.

- This comparison shows that all Western countries-including those with initial income levels reasonably similar to those in Latin America in 1950-have made substantial progress in catching up to the United States.

- In sharp contrast, no Latin American country has made any significant progress in catching up to the United States.

- First, the authors find that stagnant relative total factor productivity (TFP) is the key determinant of Latin America's relative income and labor productivity stagnation.

- In particular, big increases in barriers to competition are followed by large productivity decreases, and big decreases in these barriers are followed by large productivity increases.

2. A Neoclassical Framework

- The authors use the neoclassical growth model to guide their analysis.

- For their empirical analysis, the authors will assume that U.S. TFP is a reasonable proxy for the world technology frontier, which implies that η US = 1.

- This simple model generates long-run income differences between countries through two channels: (1) through the relative efficiency term η and (2) through differences in the relative supplies of capital and labor, which in their model are governed by country-specific preference differences.

- Note that any factor that affects income in the long-run-such as tax distortions-will manifest itself as a change in either one or both of these two channels.

- The authors will first use this model to gauge how important these two channels are for understanding Latin American macroeconomic development.

3. Latin America's Persistent Economic Stagnation

- This section examines Latin America's long-run macroeconomic performance, which the authors measure as per capita income relative to that of the world frontier (U.S. per capita income).

- Interpreting the income gap between Latin America and the United States requires a benchmark that lets us assess how large of a gap should be expected today, and how much this gap should have changed over the last 50 years.

- Commonality leads us to assume that Latin America and the other Western countries should have the same innate ability to learn and adopt successful Western technologies, and that with similar cultures, they should have similar preferences for market goods.

- If TFP is the dominant factor, then the authors should be formulating explanations for why production efficiency is so much lower in Latin America than in the United States.

- This latter impact is observed in the Euler equation that governs capital accumulation.

5. Human Capital Is Not a Major Factor

- The authors analysis has measured labor services as employment, without any adjustment for differences in human capital between regions.

- Moreover, a human capital-based explanation makes two other empirical predictions: (1) Latin America should have a very low ratio of human capital to output compared to the United States, and (2) Latin American TFP levels should be similar to those in the United States after adjusting TFP for human capital differences between the two regions.

- The authors will show that neither of these predictions is consistent with the data.

- A third reason that human capital is not the central factor accounting for Latin America's TFP gap is because a large gap between the United States and Latin America remains after adjusting for human capital differences.

- Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare, using 1985 data and some different procedures, find that these countries have an average of 67 percent of U.S. TFP.

6. Latin American Stagnation and Competitive Barriers

- A very old view, extending back to at least Adam Smith, argues that barriers to competition will discourage innovation.

- According to this view, countries that have more competitive barriers will be poorer.

- A major rationalizing element in these models is that a subset of society would be harmed by the adoption of superior technologies, and this subset has sufficient resources to successfully block their adoption.

- In all of these papers, lowering competition reduces productivity through the channel of "X-inefficiency," in which an organization fails to produce at its minimum cost.

- In the next section the authors establish that Latin America erects significantly more competitive barriers than the successful countries in Europe and Asia.

7. Latin America Puts Up Significant Competitive Barriers

- The authors now focus on government policies that restrict competition.

- The authors will examine a number of different types of barriers that they categorize as either international competitive barriers, including tariffs, quotas, multiple exchange rate systems, and regulatory barriers to foreign producers, and domestic competitive barriers, including entry barriers, inefficient financial systems, and large, subsidized state-owned enterprises.

- The authors will present evidence that shows that Latin America has constructed many international and domestic barriers that have closed off Latin America from both internal and external competition.

- Loayza and Palacios (1997) show that average tariff rates in Latin America were about 38 percent between 1984 and 1987, compared to 16 percent for East Asia.

- In the language of their model, this means openness can affect the level of η in a country, and this permanent change in η would be associated with temporarily higher growth associated with transitional capital accumulation dynamics.

B. Latin America's Domestic Competitive Barriers: High Entry Barriers

- Latin America has systematically higher domestic competitive barriers than the European and Asian successes, including (i) high entry costs, (ii) poorly functioning capital markets, and (iii) high costs of adjusting the workforce or building up an experienced workforce.

- Entry costs can be an important competitive barrier because they reduce the incentive for firms to enter an industry.

- These data suggest that entry costs are indeed much higher in Latin America, and constitute a potentially important competitive barrier.

- These data are from La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (2002).

- In summarizing the results of a collection of studies on Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) labor markets, Heckman and Pages (2003) conclude that while the overall costs of labor market regulation are quite similar in LAC and OECD countries, the LAC countries impose these costs much more in the form of job security measures than in social security provisions.

8. Microeconomic Evidence on the Impact of Competition

- The authors now present microeconomic evidence from Latin America that shows how productivity and output change when there is a change in competition.

- They conduct industry-level analyses in which there is a large, exogenous change in competition, and in which productivity is easy to measure both before and after the competitive change.

- The authors follow this approach here by presenting industry cases in which there are large and exogenous government policy changes that significantly affect the level of competition.

- The authors then present five cases that show the adoption of policies that foster competition are associated with large productivity and output gains.

- The authors call the first type of barrier entry impediments, which keep high productivity firms out of an industry.

A. Eliminating Competition in the Venezuelan Oil Industry

- The authors now provide an important case where nationalization eliminated foreign competition and reduced productivity substantially in a major sector.

- The authors discussion draws on recent work by Restuccia and Schmitz (2004) .

- Output and productivity continued to fall after the nationalization.

- By 1995, which is the ending year for their data, output had returned only to its 1963 level, and productivity had returned only to its 1960 level.

- The authors conclude that nationalization of the Venezuelan oil industry, which eliminated the efficient international management of the industry, led to large productivity and output losses.

B. Eliminating Competition in the Venezuelan Iron Industry

- Restuccia and Schmitz (2004) also show that Venezuela followed a similar nationalization policy with its iron ore industry, with similar results.

- The output and productivity patterns mirror those from the oil industry.

- Both output and productivity rose significantly until just before nationalization, with output growing at 6.1 percent per year and productivity growing at 11.5 percent per year from 1953 to 1974.

- By 1983, output was 62 percent below its 1974 peak level and productivity was 58 percent below its peak level.

- The authors now turn their attention to the impact of policy changes that increase competition.

C. Allowing Entry in Chile's Copper Industry

- The authors first show that bringing foreign competition to Chile's copper industry is associated with a large and permanent increase in productivity and output.

- Figures 13 and 14 show how output, productivity, and Codelco's industry share changed with the introduction of foreign competition.

- Garcia, Knights, and Tilton (2001) show that about 30 percent of the productivity gain was from higher efficiency at individual mines, while 70 percent of the gain was from shifting location, that is, from the production of new entrants.

- Figure 15 shows that Chile's rapid post-reform productivity growth significantly reduced the labor productivity gap between Chile and the United States.

D. Reversing Quotas in Brazil's Computer Industry

- The authors now show how eliminating a zero quota policy in Brazil's computer industry is associated with a large increase in output and productivity.

- The policy thus insulated Brazilian computer producers from foreign competition, and the policy also featured entry barriers to new firms through a maze of bureaucratic requirements.

- Moreover, prices fell substantially immediately after Collor's election.

- Since productivity growth in the U.S. computer industry has been estimated to be around 30 percent per year, 16 this means that Brazil had only about 20 percent of the U.S. productivity level in 1989 prior to the reforms.

- 17 Imports rose 150 percent with the new policy, but despite this increase in foreign competition, many of the Brazilian firms were able to successfully compete.

E. Privatizing State-Owned Enterprises: Brazilian Iron Ore

- The authors next analyze the privatization of the Brazilian iron ore industry.

- Plans to sell CVRD also began in the early 1990s, and this led CVRD to change its organization structure in preparation for privatization.

- Prior to privatization, work rules placed significant limitations on the number of tasks a worker could perform.

- Productivity grew about 140 percent between 1990 and 1997, and output grew about 30 percent during this period.

- As in the case of the Chilean copper industry, the Brazilian iron ore industry produced more output with significantly fewer workers following the policy reform.

F. The Large-Scale Privatization of Mexican SOEs

- The authors now explore larger-scale Latin American privatizations.

- The authors discussion draws on work by La Porta and Lopez-de-Silanes (1999).

- Prior to the early 1980s, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) played a significant role in the Mexican economy.

- They accounted for about 14 percent of GDP and about 38 percent 18 Data are available only beginning in 1986.

- For a significant fraction of the economy by removing entry impediments.

G. The Large-Scale Privatization of Argentinian SOEs

- Argentina also privatized many of its SOEs in the 1990s.

- When the government sold the enterprises, it often kept the monopoly structure in the industry to make the firm attractive to prospective buyers.

- Hence, the productivity consequences of privatization might not have been as large under this strategy.

- They also find unit costs declined 10 percent and production rose 25 percent.

- In particular, these cases suggest that Latin America indeed can achieve Western productivity levels when competitive barriers are removed.

9. Conclusion

- This is because it is the only group of Western countries that are not already rich, or that have not gained significant ground on U.S. income levels in the last 50 years.

- The authors have argued that competitive barriers are a promising route for understanding Latin America's large and persistent productivity gap.

- The authors findings also have implications for these other factors.

- The fraction of the population that speaks a Western European language, also known as **Language.

- The share of the population whose native tongue is Spanish (age 5 or higher), 1993 Census, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica (INEI), also known as Peru.

Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

Figures (9)

Table 6. Investment-to-Output Ratios by Region (Regional Averages for Selected Countries)

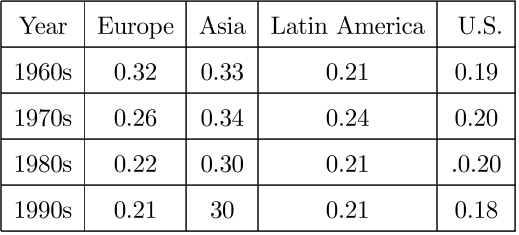

Table 4. Employment Rates by Region (Regional Averages for Selected Countries)

Table 7. Bils-Klenow Relative Human Capital Levels (Regional Averages for Selected Countries, U.S. = 100)

Table 5. Capital-to-Ouput Ratios by Decade Average Relative to the U.S.*

Table 10. Government Ownership Share of the Top 10 Banks

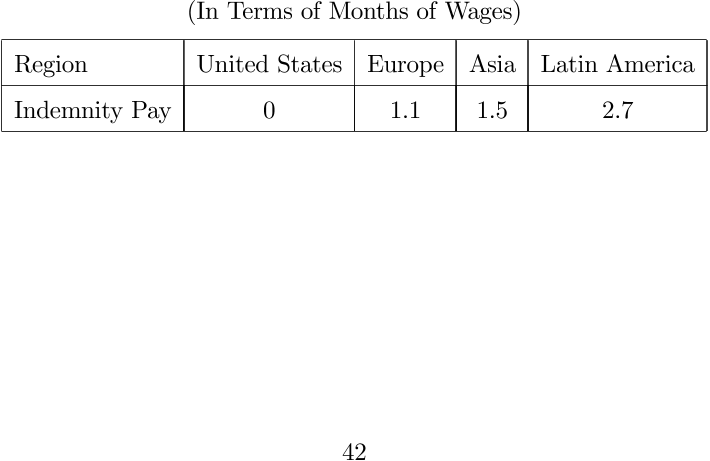

Table 11. Mandated Severance Pay

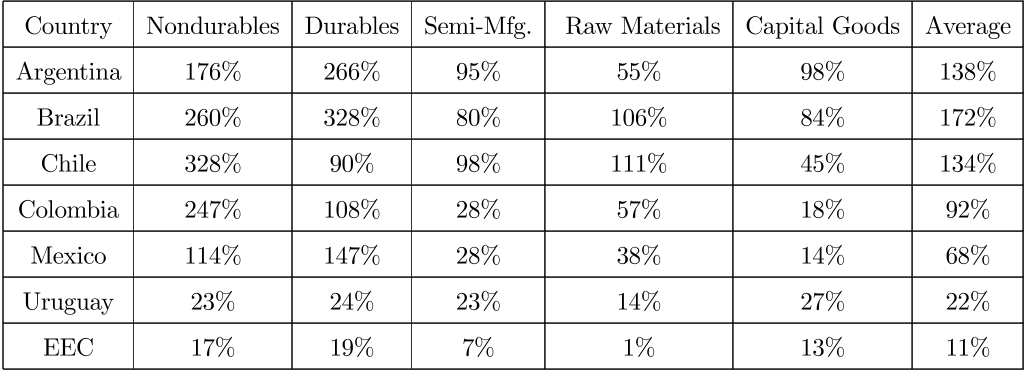

Table 8. Nominal Rates of Protection in 1960 Latin America and the EEC

Table 9. Business Start-up Costs

Table 1. Percentage of Latin American Population of Western Descent, Language and Religion

Citations

More filters

TL;DR: In this paper, the authors quantitatively analyze the role of financial frictions and resource misallocation in explaining development dynamics, and show that the model economy with financial Frictions converges to the new steady state slowly after a reform triggers efficient reallocation of resources; the transition speed is half that of the conventional neoclassical model.

Abstract: We quantitatively analyze the role of financial frictions and resource misallocation in explaining development dynamics. Our model economy with financial frictions converges to the new steady state slowly after a reform triggers efficient reallocation of resources; the transition speed is half that of the conventional neoclassical model. Furthermore, in the model economy, investment rates and total factor productivity are initially low and increase over time. We present data from the so-called miracle economies on the evolution of macro aggregates, factor reallocation, and establishment size distribution that support the aggregate and micro-level implications of our theory.

383 citations

01 Jan 2006

TL;DR: The next great globalization: A Force for Good? as mentioned in this paper discusses how poor countries can get rich: Strengthening Property Rights and the Financial System 19 Chapter Three: Financial Development, Economic Growth, and Poverty 36 Chapter Four: When Globalization goes wrong: The Dynamics of Financial Crises 49 Part Two: Financial Criss in Emerging Market Economies Chapter Five: Mexico, 1994-1995 71 Chapter Six: South Korea, 1997-1998 85 Chapter Seven: Argentina, 2001-2002 106 Part Three: How Can Disadvantaged Nations Make Financial Globalization Work for Them?

Abstract: Preface ix Chapter One: The Next Great Globalization: A Force for Good? 1 Part One: Is Financial Globalization Beneficial? Chapter Two: How Poor Countries Can Get Rich: Strengthening Property Rights and the Financial System 19 Chapter Three: Financial Development, Economic Growth, and Poverty 36 Chapter Four: When Globalization Goes Wrong: The Dynamics of Financial Crises 49 Part Two: Financial Crises in Emerging Market Economies Chapter Five: Mexico, 1994-1995 71 Chapter Six: South Korea, 1997-1998 85 Chapter Seven: Argentina, 2001-2002 106 Part Three: How Can Disadvantaged Nations Make Financial Globalization Work for Them? Chapter Eight: Ending Financial Repression: The Role of Globalization 129 Chapter Nine: Preventing Financial Crises 137 Chapter Ten: Recovering from Financial Crises 164 Part Four: How Can the International Community Promote Successful Globalization? Chapter Eleven: What Should the International Monetary Fund Do? 175 Chapter Twelve: What Can the Advanced Countries Do? 200 Part Five: Where Do We Go from Here? Chapter Thirteen: Getting Financial Globalization Right 211 Notes 221 References 277 Acknowledgments 305 Index 307

229 citations

Posted Content•

TL;DR: This paper found that educational achievement can account for between half and two thirds of the income differences between Latin America and the rest of the world in terms of economic development, and that the positive growth effect of educational achievement fully accounts for the poor growth performance of Latin American countries.

Abstract: Latin American economic development has been perceived as a puzzle. The region has trailed most other world regions over the past half century despite relatively high initial development and school attainment levels. This puzzle, however, can be resolved by considering educational achievement, a direct measure of human capital. We introduce a new, more inclusive achievement measure that comes from splicing regional achievement tests into worldwide tests. In growth regressions, the positive growth effect of educational achievement fully accounts for the poor growth performance of Latin American countries. These results are confirmed in a number of instrumental-variable specifications that exploit plausibly exogenous achievement variation stemming from historical and institutional determinants of educational achievement. Finally, a development accounting analysis finds that, once educational achievement is included, human capital can account for between half and two thirds of the income differences between Latin America and the rest of the world.

195 citations

Cites background from "Latin America in the rearview mirro..."

...Cole et al. (2005) state unequivocally that “Latin America's TFP gap is not plausibly accounted for by human capital differences” (p. 69)....

[...]

TL;DR: A review of theoretical arguments and empirical evidence for the hypothesis that agricultural productivity improvements lead to economic growth in developing countries can be found in this paper, where the authors show that there is abundant evidence for correlations between agricultural productivity increases and economic growth but little definitive evidence for a causal connection.

Abstract: In most poor countries, large majorities of the population live in rural areas and earn their livelihoods primarily from agriculture. Many rural people in the developing world are poor, and conversely, most of the world's poor people inhabit rural areas. Agriculture also accounts for a significant fraction of the economic activity in the developing world, with some 25% of value added in poor countries coming from this sector. The sheer size of the agricultural sector implies that changes affecting agriculture have large aggregate effects. Thus, it seems reasonable that agricultural productivity growth should have significant effects on macro variables, including economic growth. But these effects can be complicated. The large size of the agricultural sector does not necessarily imply that it must be a leading sector for economic growth. In fact, agriculture in most developing countries has very low productivity relative to the rest of the economy. Expanding a low-productivity sector might not be unambiguously good for growth. Moreover, there are issues of reverse causation. Economies that experience growth in aggregate output could be the beneficiaries of good institutions or good fortune that also helps the agricultural sector. Thus, even after 50 years of research on agricultural development, there is abundant evidence for correlations between agricultural productivity increases and economic growth but little definitive evidence for a causal connection. This chapter reviews theoretical arguments and empirical evidence for the hypothesis that agricultural productivity improvements lead to economic growth in developing countries. For countries with large interior populations and limited access to international markets, agricultural development is essential for economic growth. For other countries, the importance of agriculture-led growth will depend on the relative feasibility and cost of importing food. JEL classifications: O11, O13, O41, O47, Q1

183 citations

TL;DR: This paper found that educational achievement can account for between half and two thirds of the income differences between Latin America and the rest of the world in terms of economic development, and that the positive growth effect of educational achievement fully accounts for the poor growth performance of Latin American countries.

174 citations

References

More filters

TL;DR: For 98 countries in the period 1960-1985, the growth rate of real per capita GDP is positively related to initial human capital (proxied by 1960 school-enrollment rates) and negatively related to the initial (1960) level as mentioned in this paper.

Abstract: For 98 countries in the period 1960–1985, the growth rate of real per capita GDP is positively related to initial human capital (proxied by 1960 school-enrollment rates) and negatively related to the initial (1960) level of real per capita GDP. Countries with higher human capital also have lower fertility rates and higher ratios of physical investment to GDP. Growth is inversely related to the share of government consumption in GDP, but insignificantly related to the share of public investment. Growth rates are positively related to measures of political stability and inversely related to a proxy for market distortions.

9,420 citations

TL;DR: This paper showed that differences in physical capital and educational attainment can only partially explain the variation in output per worker, and that a large amount of variation in the level of the Solow residual across countries is driven by differences in institutions and government policies.

Abstract: Output per worker varies enormously across countries. Why? On an accounting basis, our analysis shows that differences in physical capital and educational attainment can only partially explain the variation in output per worker--we find a large amount of variation in the level of the Solow residual across countries. At a deeper level, we document that the differences in capital accumulation, productivity, and therefore output per worker are driven by differences in institutions and government policies, which we call social infrastructure. We treat social infrastructure as endogenous, determined historically by location and other factors captured in part by language.

7,208 citations

TL;DR: This article showed that the differences in capital accumulation, productivity, and therefore output per worker are driven by differences in institutions and government policies, which are referred to as social infrastructure and called social infrastructure as endogenous, determined historically by location and other factors captured by language.

Abstract: Output per worker varies enormously across countries. Why? On an accounting basis our analysis shows that differences in physical capital and educational attainment can only partially explain the variation in output per worker—we find a large amount of variation in the level of the Solow residual across countries. At a deeper level, we document that the differences in capital accumulation, productivity, and therefore output per worker are driven by differences in institutions and government policies, which we call social infrastructure. We treat social infrastructure as endogenous, determined historically by location and other factors captured in part by language. In 1988 output per worker in the United States was more than 35 times higher than output per worker in Niger. In just over ten days the average worker in the United States produced as much as an average worker in Niger produced in an entire year. Explaining such vast differences in economic performance is one of the fundamental challenges of economics. Analysis based on an aggregate production function provides some insight into these differences, an approach taken by Mankiw, Romer, and Weil [1992] and Dougherty and Jorgenson [1996], among others. Differences among countries can be attributed to differences in human capital, physical capital, and productivity. Building on their analysis, our results suggest that differences in each element of the production function are important. In particular, however, our results emphasize the key role played by productivity. For example, consider the 35-fold difference in output per worker between the United States and Niger. Different capital intensities in the two countries contributed a factor of 1.5 to the income differences, while different levels of educational attainment contributed a factor of 3.1. The remaining difference—a factor of 7.7—remains as the productivity residual. * A previous version of this paper was circulated under the title ‘‘The Productivity of Nations.’’ This research was supported by the Center for Economic Policy Research at Stanford and by the National Science Foundation under grants SBR-9410039 (Hall) and SBR-9510916 (Jones) and is part of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s program on Economic Fluctuations and Growth. We thank Bobby Sinclair for excellent research assistance and colleagues too numerous to list for an outpouring of helpful commentary. Data used in the paper are available online from http://www.stanford.edu/,chadj.

6,454 citations

TL;DR: This article developed a Ricardian trade model that incorporates realistic geographic features into general equilibrium and delivered simple structural equations for bilateral trade with parameters relating to absolute advantage, comparative advantage, and geographic barriers.

Abstract: We develop a Ricardian trade model that incorporates realistic geographic features into general equilibrium It delivers simple structural equations for bilateral trade with parameters relating to absolute advantage, to comparative advantage (promoting trade), and to geographic barriers (resisting it) We estimate the parameters with data on bilateral trade in manufactures, prices, and geography from 19 OECD countries in 1990 We use the model to explore various issues such as the gains from trade, the role of trade in spreading the benefits of new technology, and the effects of tariff reduction

3,782 citations

"Latin America in the rearview mirro..." refers methods in this paper

...Following Eaton and Kortum (2002) and Alvarez and Lucas (2004), we plot the log of the trade share against the log of GDP....

[...]

TL;DR: In this article, the authors present new data on the regulation of entry of start-up firms in 85 countries, covering the number of procedures, official time, and official cost that a startup must bear before it can operate legally.

Abstract: We present new data on the regulation of entry of start-up firms in 85 countries. The data cover the number of procedures, official time, and official cost that a start-up must bear before it can operate legally. The official costs of entry are extremely high in most countries. Countries with heavier regulation of entry have higher corruption and larger unofficial economies, but not better quality of public or private goods. Countries with more democratic and limited governments have lighter regulation of entry. The evidence is inconsistent with public interest theories of regulation, but supports the public choice view that entry regulation benefits politicians and bureaucrats.

2,811 citations