"2-:)67-8=3*)227=0:%2-%"2-:)67-8=3*)227=0:%2-%

',30%60=311327 ',30%60=311327

-2%2')%4)67 #,%6832%'908=)7)%6',

-59-(-8=-7/%2(<4)'8)( 83'/)89627-59-(-8=-7/%2(<4)'8)( 83'/)89627

Ľ9&3šA7836

3&)68 8%1&%9+,

"2-:)67-8=3*)227=0:%2-%

3003;8,-7%2(%((-8-32%0;36/7%8,88476)437-836=94)22)(9*2')$4%4)67

%683*8,)-2%2')%2(-2%2'-%0%2%+)1)28311327

)'311)2()(-8%8-32)'311)2()(-8%8-32

A7836Ľ 8%1&%9+,-59-(-8=-7/%2(<4)'8)( 83'/)89627

3962%03*30-8-'%0

'3231=

,884(<(3-36+

!,-74%4)6-74378)(%8 ',30%60=311327,88476)437-836=94)22)(9*2')$4%4)67

36136)-2*361%8-3240)%7)'328%'86)437-836=43&3<94)22)(9

-59-(-8=-7/%2(<4)'8)( 83'/)89627-59-(-8=-7/%2(<4)'8)( 83'/)89627

&786%'8&786%'8

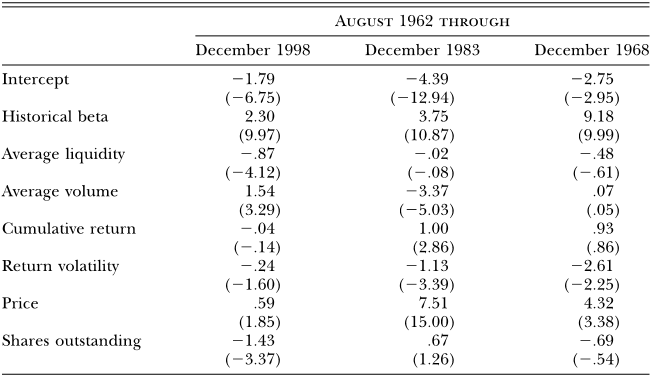

!,-7789(=-2:)78-+%8)7;,)8,)61%6/)8;-()0-59-(-8=-7%78%8):%6-%&0)-14368%28*36%77)846-'-2+#)

?2(8,%8)<4)'8)(783'/6)89627%6)6)0%8)('6377‐7)'8-32%00=838,)7)27-8-:-8-)73*6)8962783@9'89%8-327

-2%++6)+%8)0-59-(-8=961328,0=0-59-(-8=1)%796)%2%:)6%+)3*-2(-:-(9%0‐783'/1)%796)7)78-1%8)(

;-8,(%-0=(%8%6)0-)7328,)46-2'-40)8,%836()6@3;-2(9')7+6)%8)66)89626):)67%07;,)20-59-(-8=-7

03;)66318,639+,8,)%:)6%+)6)896232783'/7;-8,,-+,7)27-8-:-8-)7830-59-(-8=)<'))(7

8,%8*36783'/7;-8,03;7)27-8-:-8-)7&=4)6')28%229%00=%(.978)(*36)<43796)7838,)1%6/)86)8962

%7;)00%77->):%09)%2(131)2891*%'8367968,)6136)%0-59-(-8=6-7/*%'836%''39287*36,%0*3*8,)

463?8783%131)2891786%8)+=3:)68,)7%1)‐=)%64)6-3(

-7'-40-2)7-7'-40-2)7

-2%2')%2(-2%2'-%0%2%+)1)28

!,-7.3962%0%68-'0)-7%:%-0%&0)%8 ',30%60=311327,88476)437-836=94)22)(9*2')$4%4)67

642

[Journal of Political Economy, 2003, vol. 111, no. 3]

䉷 2003 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0022-3808/2003/11103-0006$10.00

Liquidity Risk and Expected Stock Returns

L

ˇ

ubosˇPa´stor

University of Chicago, National Bureau of Economic Research, and Centre for Economic Policy

Research

Robert F. Stambaugh

University of Pennsylvania and National Bureau of Economic Research

This study investigates whether marketwide liquidity is a state variable

important for asset pricing. We find that expected stock returns are

related cross-sectionally to the sensitivities of returns to fluctuations

in aggregate liquidity. Our monthly liquidity measure, an average of

individual-stock measures estimated with daily data, relies on the prin-

ciple that order flow induces greater return reversals when liquidity

is lower. From 1966 through 1999, the average return on stocks with

high sensitivities to liquidity exceeds that for stocks with low sensitiv-

ities by 7.5 percent annually, adjusted for exposures to the market

return as well as size, value, and momentum factors. Furthermore, a

liquidity risk factor accounts for half of the profits to a momentum

strategy over the same 34-year period.

Research support from the Center for Research in Security Prices and the James S.

Kemper Faculty Research Fund at the Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago,

is gratefully acknowledged (Pa´stor). We are grateful for comments from Nick Barberis,

John Campbell, Tarun Chordia, John Cochrane (the editor), George Constantinides, Doug

Diamond, Andrea Eisfeldt, Gene Fama, Simon Gervais, David Goldreich, Gur Huberman,

Michael Johannes, Owen Lamont, Andrew Metrick, Mark Ready, Hans Stoll, Dick Thaler,

Rob Vishny, Tuomo Vuolteenaho, Jiang Wang, and two anonymous referees, as well as

workshop participants at Columbia University, Harvard University, New York University,

Stanford University, University of Arizona, University of California at Berkeley, University

of Chicago, University of Florida, University of Pennsylvania, Washington University, the

Review of Financial Studies Conference on Investments in Imper fect Capital Markets at

Northwestern University, the Fall 2001 NBER Asset Pricing meeting, and the 2002 Western

Finance Association meetings.

liquidity risk 643

I. Introduction

In standard asset pricing theory, expected stock returns are related cross-

sectionally to returns’ sensitivities to state variables with pervasive effects

on investors’ overall welfare. A security whose lowest returns tend to

accompany unfavorable shifts in that welfare must offer additional com-

pensation to investors for holding the security. Liquidity appears to be

a good candidate for a priced state variable. It is often viewed as an

important feature of the investment environment and macroeconomy,

and recent studies find that fluctuations in various measures of liquidity

are correlated across assets.

1

This empirical study investigates whether

marketwide liquidity is indeed priced. That is, we ask whether cross-

sectional differences in expected stock returns are related to the sen-

sitivities of returns to fluctuations in aggregate liquidity.

It seems reasonable that many investors might require higher ex-

pected returns on assets whose returns have higher sensitivities to ag-

gregate liquidity. Consider, for example, any investor who employs some

form of leverage and faces a margin or solvency constraint, in that if

his overall wealth drops sufficiently, he must liquidate some assets to

raise cash. If he holds assets with higher sensitivities to liquidity, then

such liquidations are more likely to occur when liquidity is low, since

drops in his overall wealth are then more likely to accompany drops in

liquidity. Liquidation is costlier when liquidity is lower, and those greater

costs are especially unwelcome to an investor whose wealth has already

dropped and who thus has higher marginal utility of wealth. Unless the

investor expects higher returns from holding these assets, he would

prefer assets less likely to require liquidation when liquidity is low, even

if these assets are just as likely to require liquidation on average.

2

The well-known 1998 episode involving Long-Term Capital Manage-

ment (LTCM) seems an acute example of the liquidation scenario above.

1

Chordia, Roll, and Subrahmanyam (2000), Lo and Wang (2000), Hasbrouck and Seppi

(2001), and Huberman and Halka (2002) empirically analyze the systematic nature of

stock market liquidity. Chordia, Sarkar, and Subrahmanyam (2002) find that improvements

in stock market liquidity are associated with monetary expansions and that fluctuations

in liquidity are correlated across stocks and bond markets. Eisfeldt (2002) develops a

model in which endogenous fluctuations in liquidity are correlated with real fundamentals

such as productivity and investment.

2

This economic story has yet to be formally modeled, but recent literature presents

related models that lead to the same basic result. Lustig (2001) develops a model in which

solvency constraints give rise to a liquidity risk factor, in addition to aggregate consumption

risk, and equity’s sensitivity to the liquidity factor raises its equilibrium expected return.

Holmstro¨m and Tirole (2001) also develop a model in which a security’s expected return

is related to its covariance with aggregate liquidity. Unlike more standard models, their

model assumes risk-neutral consumers and is driven by liquidity demands at the corporate

level. Acharya and Pedersen (2002) develop a model in which each asset’s return is net

of a stochastic liquidity cost, and expected returns are related to return covariances with

the aggregate liquidity cost (as well as to three other covariances).

644 journal of political economy

The hedge fund was highly levered and by design had positive sensitivity

to marketwide liquidity, in that many of the fund’s spread positions,

established across a variety of countries and markets, went long less

liquid instruments and short more liquid instruments. When the Russian

debt crisis precipitated a widespread deterioration in liquidity, LTCM’s

liquidity-sensitive portfolio dropped sharply in value, triggering a need

to liquidate in order to meet margin calls. The anticipation of costly

liquidation in a low-liquidity environment then further eroded LTCM’s

position. (The liquidation was eventually overseen by a consortium of

14 institutions organized by the New York Federal Reserve.) Even though

exposure to liquidity risk ultimately spelled LTCM’s doom, the fund

performed quite well in the previous four years, and presumably its

managers perceived high expected returns on its liquidity-sensitive

positions.

3

Liquidity is a broad and elusive concept that generally denotes the

ability to trade large quantities quickly, at low cost, and without moving

the price. We focus on an aspect of liquidity associated with temporary

price fluctuations induced by order flow. Our monthly aggregate li-

quidity measure is a cross-sectional average of individual-stock liquidity

measures. Each stock’s liquidity in a given month, estimated using that

stock’s within-month daily returns and volume, represents the average

effect that a given volume on day d has on the return for day d ⫹ 1,

when the volume is given the same sign as the return on day d. The

basic idea is that, if signed volume is viewed roughly as “order flow,”

then lower liquidity is reflected in a greater tendency for order flow in

a given direction on day d to be followed by a price change in the

opposite direction on day Essentially, lower liquidity correspondsd ⫹ 1.

to stronger volume-related return reversals, and in this respect our li-

quidity measure follows the same line of reasoning as the model and

empirical evidence presented by Campbell, Grossman, and Wang

(1993). They find that returns accompanied by high volume tend to be

reversed more strongly, and they explain how this result is consistent

with a model in which some investors are compensated for accommo-

dating the liquidity demands of others.

We find that stocks’ “liquidity betas,” their sensitivities to innovations

in aggregate liquidity, play a significant role in asset pricing. Stocks with

higher liquidity betas exhibit higher expected returns. In particular,

between January 1966 and December 1999, a spread between the top

and bottom deciles of predicted liquidity betas produces an abnormal

return (“alpha”) of 7.5 percent per year with respect to a model that

accounts for sensitivities to four other factors: the market, size, and value

factors of Fama and French (1993) and a momentum factor. The alpha

3

See, e.g., Jorion (2000) and Lowenstein (2000) for accounts of the LTCM experience.