Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model

Author(s): Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman

Source:

The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

Vol. 106, No. 4 (Nov., 1991), pp. 1039-1061

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937956 .

Accessed: 26/04/2011 00:37

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oup. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Quarterly

Journal of Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

LOSS AVERSION IN

RISKLESS CHOICE:

A

REFERENCE-DEPENDENT MODEL*

AMos TVERSKY AND

DANIEL

KAHNEMAN

Much

experimental evidence indicates that

choice depends on the status quo or

reference level:

changes of reference point often

lead to reversals of preference. We

present

a

reference-dependent theory of consumer

choice, which explains such

effects

by a

deformation of indifference curves

about the reference point. The

central

assumption of the theory is that losses and

disadvantages have greater

impact on

preferences

than

gains

and

advantages.

Implications of loss aversion for

economic

behavior

are

considered.

The

standard models

of

decision

making assume that prefer-

ences

do

not

depend

on

current assets.

This assumption greatly

simplifies

the

analysis

of

individual choice

and

the

prediction

of

trades:

indifference

curves are

drawn without

reference

to

current

holdings, and the

Coase theorem asserts

that, except for transac-

tion

costs,

initial

entitlements

do not affect

final

allocations.

The

facts

of

the

matter are

more

complex.

There

is

substantial evidence

that

initial entitlements

do

matter and

that

the rate of exchange

between

goods

can

be quite different

depending

on

which is

acquired

and

which

is

given up,

even

in

the

absence

of

transaction

costs or

income

effects.

In

accord with a

psychological analysis

of

value,

reference levels play

a

large role

in

determining preferences.

In the present

paper we review the

evidence for this proposition

and offer a

theory

that

generalizes

the

standard model

by introduc-

ing a reference

state.

The

present analysis

of

riskless choice

extends

our

treatment

of

choice

under

uncertainty [Kahneman

and

Tversky, 1979, 1984;

Tversky

and

Kahneman, 1991], in which

the outcomes

of

risky

prospects

are

evaluated by

a

value function

that has three essential

characteristics.

Reference dependence:

the

carriers of

value are

gains

and

losses defined relative to a reference

point.

Loss

aversion:

the

function

is

steeper

in

the

negative

than

in

the

positive domain;

losses

loom

larger

than

corresponding

gains. Diminishing sensitiv-

ity:

the

marginal value

of

both

gains and

losses decreases with their

*This

paper has benefited from

the

comments of

Kenneth Arrow, Peter

Diamond,

David

Krantz,

Matthew

Rabin, and

Richard Zeckhauser. We are espe-

cially grateful

to

Shmuel

Sattath and

Peter

Wakker

for

their helpful suggestions.

This work

was

supported by

Grants

No. 89-0064

and

88-0206

from

the

Air

Force

Office of

Scientific

Research,

and

by

the Sloan

Foundation.

?

1991

by the President

and

Fellows

of

Harvard

College

and

the

Massachusetts Institute

of

Technology.

The

Quarterly Journal

of Economics, November

1991

1040

QUARTERLY

JOURNAL OF

ECONOMICS

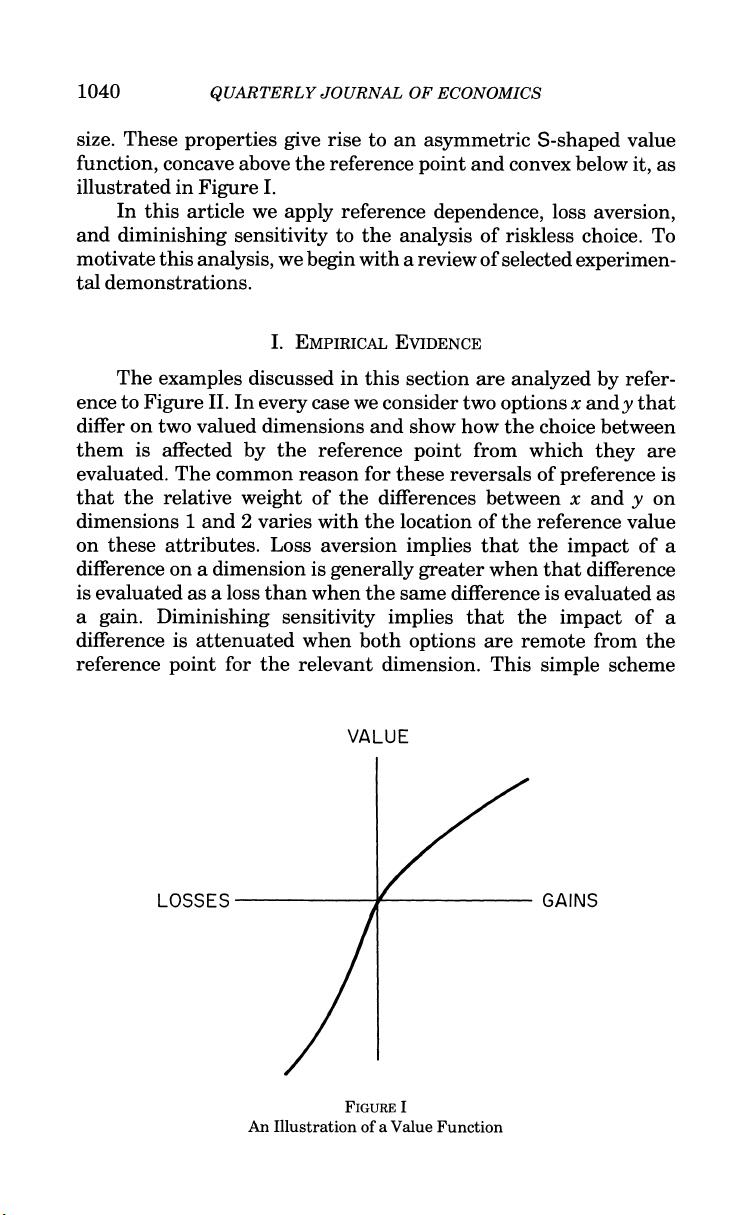

size.

These

properties

give rise to an

asymmetric

S-shaped value

function,

concave above

the

reference point

and

convex

below it,

as

illustrated in

Figure

I.

In this

article

we apply

reference

dependence, loss

aversion,

and

diminishing

sensitivity

to the

analysis

of

riskless

choice.

To

motivate

this

analysis,

we

begin with a

review

of

selected

experimen-

tal

demonstrations.

I.

EMPIRICAL

EVIDENCE

The

examples

discussed in

this

section are

analyzed

by refer-

ence

to

Figure

II.

In

every

case

we

consider two

options

x

andy

that

differ

on

two valued

dimensions and show how

the

choice between

them is

affected

by

the

reference

point

from which

they

are

evaluated. The common

reason

for

these

reversals

of

preference

is

that the

relative

weight

of the

differences between x

and

y

on

dimensions

1

and 2

varies with the location of

the

reference value

on these

attributes.

Loss

aversion

implies

that the

impact

of a

difference on

a

dimension

is

generally greater

when

that

difference

is

evaluated

as a loss than

when

the same

difference is

evaluated

as

a

gain.

Diminishing

sensitivity implies

that the

impact

of

a

difference

is attenuated when both

options

are remote from

the

reference point for the

relevant

dimension. This

simple scheme

VALUE

LOSSES

GAINS

FIGURE

I

An

Illustration of

a

Value

Function

LOSS

AVERSION IN

RISKLESS

CHOICE

1041

serves

to

organize

a

large

set of

observations.

Although

isolated

findings

may be subject to

alternative

interpretations,

the

entire

body of

evidence provides

strong

support

for

the phenomenon of

loss aversion.

a. Instant

Endowment. An

immediate

consequence

of

loss

aversion is that

the loss

of

utility associated with

giving up

a

valued

good

is

greater than the

utility gain associated with

receiving

it.

Thaler

[1980]

labeled this

discrepancy the

endowment

effect,

because

value

appears

to

change when a

good

is

incorporated

into

one's endowment. Kahneman, Knetsch, and

Thaler

[1990] tested

the endowment effect

in

a

series

of

experiments,

conducted

in

a

classroom

setting.

In

one

of

these

experiments

a

decorated

mug

(retail value

of

about

$5) was

placed

in

front

of one third of

the

seats

after

students had chosen their

places.

All

participants

received a

questionnaire.

The

form

given

to

the recipients

of

a

mug

(the

"sellers")

indicated that "You now own

the

object

in

your

possession. You have the

option

of

selling

it

if

a

price,

which

will

be

determined

later,

is

acceptable

to

you.

For

each

of the

possible

prices

below

indicate whether

you

wish to

(x) Sell

your

object and

receive this

price;

(y) Keep your

object and take it home

with

you...."

The

subjects indicated their decision for

prices

ranging

from

$0.50

to

$9.50

in

steps

of

50

cents. Some of the

students who

had not

received a

mug (the

"choosers")

were given

a

similar

questionnaire,

informing

them

that

they

would have the

option

of

receiving

either

a

mug

or

a sum

of

money

to

be determined

later.

They indicated their

preferences between

a

mug

and

sums

of

money

ranging

from

$0.50

to

$9.50.

The

choosers and the

sellers

face

precisely the same

decision

problem,

but

their reference

states differ.

As

shown

in

Figure II,

the choosers'

reference state

is

t,

and

they

face

a

positive

choice

between two

options

that

dominate

t;

receiving

a

mug

or

receiving

a sum

in

cash. The

sellers evaluate the same

options

from

y; they

must choose

between

retaining

the

status

quo

(the mug)

or

giving

up

the

mug

in

exchange

for

money.

Thus,

the

mug

is evaluated as a

gain by

the

choosers,

and as

a loss

by

the

sellers. Loss

aversion

entails that

the rate

of

exchange

of

the

mug

against

money

will be

different

in

the

two

cases.

Indeed,

the median

value

of

the

mug

was

$7.12

for

the

sellers and

$3.12

for

the choosers

in

one

experiment,

$7.00

and

$3.50

in

another.

The difference

between these

values

reflects an

endowment effect

which

is

produced, apparently

instan-

1042

Q

UAR TERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

S0o

0

ci)

E t

----

x

cz~~~~~~~~~~~r

o~~~~~~~~s

Dimension

1

FIGURE II

Multiple Reference

Points for the Choice Between x and

y

taneously, by giving

an individual

property rights

over a

consump-

tion

good.

The interpretation of the endowment effect may be illumi-

nated by

the

following thought experiment.

Imagine

that as

a

chooser

you prefer $4

over

a

mug.

You learn

that

most

sellers

prefer

the

mug

to

$6,

and

you

believe that

if

you

had

the

mug you

would

do

the

same.

In

light

of this

knowledge,

would

you

now

prefer

the

mug

over

$5?

If

you do, it is presumably because you have changed your

assessment

of the

pleasure

associated with

owning

the

mug.

If

you

still

prefer $4

over the

mug-which

we

regard

as

a

more

likely

response this indicates that you interpret

the

effect

of endow-

ment as

an

aversion

to

giving up your mug

rather than as an

unanticipated

increase

in

the

pleasure

of

owning

it.

b. Status

Quo

Bias. The retention of the status

quo

is an

option

in

many

decision

problems.

As illustrated

by

the

analysis

of

the sellers'

problem

in

the

example

of the

mugs,

loss

aversion

induces a bias that favors

the

retention

of

the status

quo

over other

options.

In

Figure II,

a decision maker who is indifferent between x

and

y

from

t

will

prefer

x

over

y

from

x,

and

y

over x

from y.

Sarnuelson

and Zeckhauser

[1988]

introduced the term "status

quo

bias"

for

this effect

of

reference

position.