Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

183 citations

7 citations

1 citations

1 citations

...4 This section relies heavily on my previous work (Merrino 2020)....

[...]

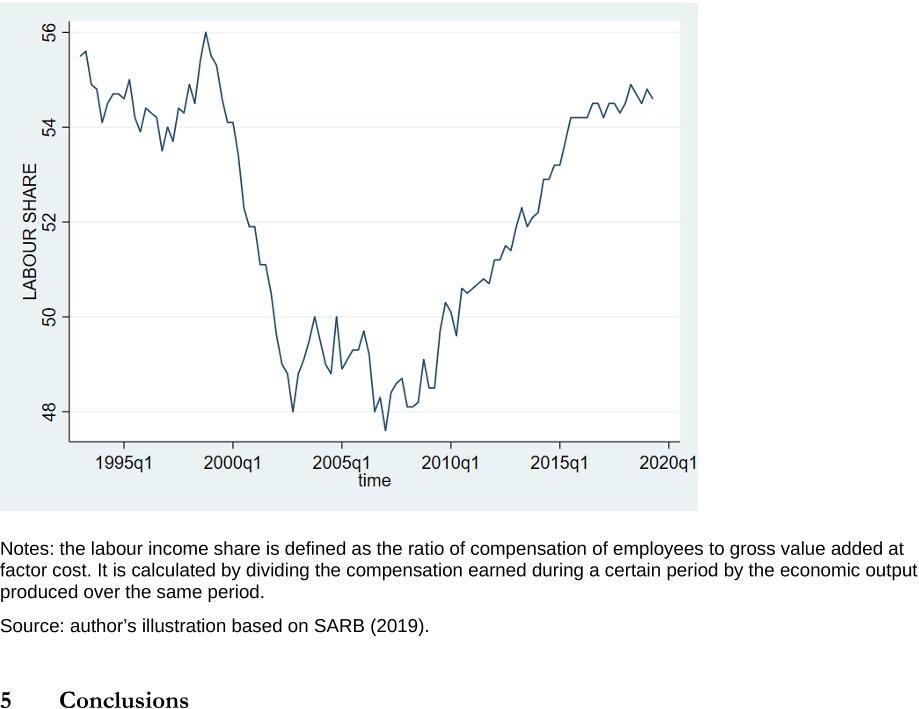

...If this is the case, the functional distribution of income remains overall an inadequate proxy for labour income inequality in the South African case (Merrino 2020)....

[...]

...By looking at the evolution of the labour share in the post-apartheid era, it emerges that it has been moving in the same direction as wage inequality (Merrino 2020)....

[...]

1 citations

...This analysis exploits the recent improvement of the household survey data integrated in the Post-Apartheid Labour Market Series (PALMS), which allows a reliable comparison over time of inequality measures (Merrino 2020)....

[...]

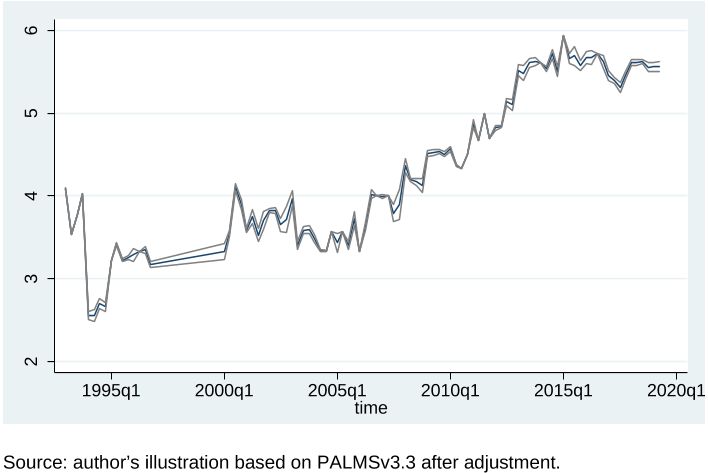

...The harmonized data include the Household Surveys from 1994 to 1999, the Labour Force Surveys from 2000 to 2007, and the Quarterly Labour Force Surveys from 2008 to 2019 (see Finn and Leibbrandt 2018; Kerr and Wittenberg 2019; Merrino 2020)....

[...]

183 citations

...The process of PMM imputation is repeated m times to obtain m imputed data sets to be eventually analysed as though they were complete (Rubin 1987)....

[...]

179 citations

151 citations

...As already observed by Casale et al. (2004) and Leibbrandt et al. (2010), Wittenberg and Pirouz (2013) also evidence how the change in coverage between the OHSs and the successive LFSs generated a gap in the earnings series at the year 2000. Wittenberg and Pirouz conclude by arguing that it is possible to identify some real wage growth since 2000 despite the noise generated by these measurement changes. Wittenberg (2014b) builds on the previous paper to compare PALMS to firm-level data— namely the Survey of Employment and Earnings (SEE) and the Quarterly Employment Statistics (QES) surveys....

[...]

...However, as the demographic information contained in new censuses changes, later surveys are calibrated to previous aggregates that have become obsolete (Branson and Wittenberg 2014; Casale et al. 2004)....

[...]

...Casale et al. (2004) use only the OHS 1995 and the LFS 2001:2 to analyse the position of women and ethnic groups in the labour market....

[...]

...As already observed by Casale et al. (2004) and Leibbrandt et al. (2010), Wittenberg and Pirouz (2013) also evidence how the change in coverage between the OHSs and the successive LFSs generated a gap in the earnings series at the year 2000. Wittenberg and Pirouz conclude by arguing that it is possible to identify some real wage growth since 2000 despite the noise generated by these measurement changes. Wittenberg (2014b) builds on the previous paper to compare PALMS to firm-level data— namely the Survey of Employment and Earnings (SEE) and the Quarterly Employment Statistics (QES) surveys. He adds that the top tail of the earnings distribution has received larger gains than the 75th percentile; that both of them show significant real earnings growth; that the 10th percentile made real gains relative to the median, therefore experiencing a compression; and that among the self-employed there is no evidence for systematic shifts in the distribution over the post-apartheid period. Wittenberg (2017c) effects further adjustments to yield PALMSv2....

[...]

...As already observed by Casale et al. (2004) and Leibbrandt et al....

[...]

97 citations

...While all previously mentioned authors rely on a few points in time, the most comprehensive study on long-run trends in labour income inequality in South Africa can be found in the work of University of Cape Town’s Martin Wittenberg, which indeed serves as the basis for this discussion. Wittenberg and Pirouz (2013) use PALMSv2 to show the impact of different types of data quality adjustments (specifically they treat outliers, zero earnings, bracket responses, and missing observations) on the estimation of the average wage over the period 1994–2011....

[...]

...A number of studies compare the QLFS earnings data against other sources, particularly administrative data released by the South African Revenue Service since 2011, and suggest that it under-reports high incomes (Bassier and Woolard 2018; Seekings 2007; van der Berg et al. 2007; Wittenberg 2014a, 2017a)....

[...]

...…of studies compare the QLFS earnings data against other sources, particularly administrative data released by the South African Revenue Service since 2011, and suggest that it under-reports high incomes (Bassier and Woolard 2018; Seekings 2007; van der Berg et al. 2007; Wittenberg 2014a, 2017a)....

[...]

...While all previously mentioned authors rely on a few points in time, the most comprehensive study on long-run trends in labour income inequality in South Africa can be found in the work of University of Cape Town’s Martin Wittenberg, which indeed serves as the basis for this discussion....

[...]

63 citations

...Cichello et al. (2005) compare 1993 and 1998 earnings in the KwaZulu Natal Income Dynamics Study and reach different results when using the data as a panel and as a cross-section....

[...]