Price indexes, inequality, and the measurement of world poverty

Angus Deaton, Princeton University

January 10

th

, 2010

ABSTRACT

I discuss the statistical basis for measures of world poverty and inequality, with particular

attention to the role of purchasing power parity price indexes from the International

Comparison Project. Global inequality increased sharply with the latest revision of the ICP,

but the recent large increase in global poverty came from an inappropriate updating of the

global line, not from the ICP revision. ICP comparisons between widely different countries

rest on weak empirical and theoretical foundations. I argue for greater use of self-reports in

international monitoring surveys, and for a global poverty line that is denominated in US

dollars.

Presidential Address, American Economic Association, Atlanta, January 2010. I am grateful

to Olivier Dupriez, Alan Heston and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl who have collaborated with me

on related work, to them and to Erwin Diewert, Yuri Dikhanov, D. S. Prasada-Rao, and Fred

Vogel who have over the years taught me about international price comparisons, as well as

the Development Economics Data Group at the World Bank for supplying me with data and

for their patience and help with my questions. I also thank Tony Atkinson, Tim Besley,

Branko Milanovic, François Bourguignon, Anne Case, Olivier Dupriez, Bill Easterly, Alan

Heston and Martin Ravallion for comments on partial drafts. The views expressed here are my

own.

1

This lecture is about counting the number of poor people in the world. If we ask people

whether they consider themselves to be poor, or how much money someone would need to get

by in their community, they appear to have little difficulty in replying. Beyond the local level,

many countries, including the United States, regularly publish national counts of the number

of people in poverty, and while these numbers and the procedures for calculating them are

contested and debated, the estimates typically carry sufficient legitimacy to support policy,

see Connie Citro and Robert Michael (1995) for the history in the US, and Rebecca Blank and

Mark Greenburg (2008) for a recent proposal for reform. But once we try to calculate the

number of poor people in the world, matters are more complicated. The World Bank’s global

poverty count, which started with Montek Ahluwalia, Nicholas Carter and Hollis Chenery

(1979), and which became the dollar-a-day count in the World Development Report 1990, was

incorporated into international policymaking and discussion via the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs)—the first of which is to “halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of

people whose income is less than $1 a day.” This global count has an apparent transparency

that helps account for its rhetorical success: it is simply the number of people in the world

who live on less than a dollar a day, with the relevant dollar adjusted for international

differences in prices. But this transparency and simplicity is more apparent than real. There

are many complexities beneath the surface, and these are the subject matter of this paper,

particularly the calculation of the global line and the adjustment for international differences

in prices using purchasing power parity exchange rates. Price adjustment is also important for

other purposes, such as the construction of databases such as the Penn World Table, which

underpins almost all of economists’ empirical understanding of the process of economic

2

growth, as well as for the measurement of global income inequality, which is another of my

main concerns here.

One goal of this paper is to understand why almost half a billion people were moved into

poverty at the time of the revision of the purchasing power parity exchange rates in the 2005

round of the International Comparison Project (ICP). This same revision also increased global

income inequality, widening the apparent distance between poor and rich countries. I shall

argue that the increase in poverty had little to do with the ICP, and much to do with an

inappropriate increase in the global poverty line. The causes of the increase in inequality are

harder to pinpoint, but my investigations lead to skepticism about our ability to make precise

comparisons of living standards between widely different countries, for example between

poor countries in Africa and rich countries in the OECD.

In spite of the attention that they receive, global poverty and inequality measures are

arguably of limited interest. Within nations, the procedures for calculating poverty are

routinely debated by the public, the press, legislators, academics, and expert committees, and

this democratic discussion legitimizes the use of the counts in support of programs of

transfers and redistribution. Between nations where there is no supranational authority,

poverty counts have no direct redistributive role, and there is little democratic debate by

citizens, with discussion largely left to international organizations such as the United Nations

and the World Bank, and to non-governmental organizations that focus on international

poverty. These organizations regularly use the global counts as arguments for foreign aid and

for their own activities, and the data have often been effective in mobilizing giving for

poverty alleviation. They may also influence the global strategy of the World Bank,

emphasizing some regions or countries as the expense of others. It is less clear that the counts

3

have any direct relevance for those included in them, given that national policymaking and the

country operations of the World Bank depend on local, not global poverty measures. Global

poverty and global inequality measures have a central place in a cosmopolitan vision of the

world, in which international organizations such as the UN and the World Bank are somehow

supposed to fulfill the redistributive role of the missing global government, see for example

Thomas Pogge (2002) or Peter Singer (2002). For those who do not accept the cosmopolitan

vision as morally compelling or descriptively accurate, such measures are less relevant, John

Rawls (1999), Thomas Nagel (2005), Leif Wenar (2006).

The paper is organized as follows. Section I explains how the dollar a day poverty

numbers are calculated and how they depend on purchasing power parity exchange rates. It

shows that poverty measures are sensitive to the PPPs used in their construction, and

establishes the basic facts and puzzles to be addressed, particularly the increases in poverty

and inequality associated with the latest ICP revisions. Sections II and III are more technical

and can be skipped without losing the thread of the main argument. Section II discusses the

components of the construction of PPPs that are particularly important for measuring world

poverty and inequality, while Section III discusses how PPP indexes need to be reweighted

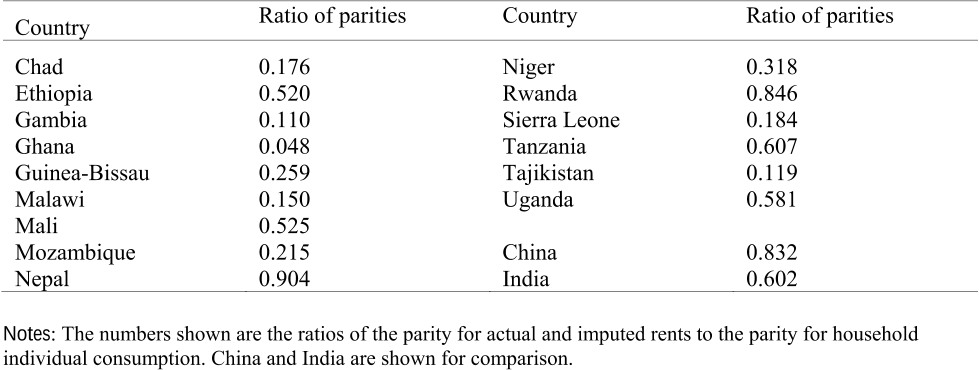

for use in poverty measurement. It argues, by reference to my related work with Olivier

Dupriez (2009), that the reweighting, although a clear conceptual improvement, matters less

than might be thought. Section IV returns to the main argument and is concerned with the

definition of the global poverty line, and I discuss ways of constructing the line based on the

international price indexes and the national poverty lines of poor countries. As is always the

case with poverty lines, how the poverty line is updated with respect to new information

deserves as much or more attention than how its original value is set. I argue that the updating

4

procedure in current use is incorrect, that it can result in reductions in national poverty

causing increases in global poverty, and that this explains why the global poverty counts

increased so much in the latest revision. Paradoxically, one of the main reasons that India (and

the rest of the world) became poorer was because India had grown too rich. I argue for a

definition of the line, and an updating method, that is substantially different from those

currently in use, and that preserves a better continuity with previous estimates.

Section V, which is again somewhat more technical, is an enquiry into the international

price indexes themselves, with a focus on the factors that affect global inequality. It starts

from the question of how to price comparable goods in different countries and whether the

ever more precise specification of goods by the ICP has had the effect of making poor

countries poorer relative to rich countries, widening our estimates of international inequality,

and causing the global poverty line to increase in dollar terms at a rate that is markedly slower

than the rate of inflation in the US. More generally, I discuss the special difficulties of making

comparisons between countries whose relative prices and patterns of consumption are very

different, for example between Japan and Kenya, or Britain and Cameroon. Such comparisons

are required if we are to make multilateral price index numbers for the world as a whole, and I

use data from the 2005 ICP to investigate their credibility. My analysis shows that these

comparisons rest on weak theoretical foundations and are fragile in practice.

Section VI returns to the main argument and looks briefly at an alternative monitoring

system based on asking people about their lives are going; I use data from the Gallup World

Poll which collects an annual sample of all the people of the world. Section VII concludes,

and speculates on the global system of income and poverty statistics as a whole. I argue that

we should be less ambitious and more skeptical in using the international data, particularly