Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

139 citations

94 citations

77 citations

46 citations

41 citations

1,489 citations

...Another system, tested with users suffering from ALS and based on SCPs was described by Birbaumer [11]....

[...]

...The voluntary production of negative and positive SCPs has been exploited by Birbaumer et al to show that patients suffering from ALS can use a BCI to control a spelling device and to communicate with their environment [11]....

[...]

895 citations

...For example for motor imagery based BCIs, it has been shown that spatial filtering with a Laplacian filter can increase performance [16]....

[...]

844 citations

...An overview of these algorithms can be found in [22]....

[...]

744 citations

722 citations

...Note that the results described here are significantly better than those obtained with other P300-based BCI systems for disabled users [35], [36]....

[...]

The main advantages of the SVM are that it allows to achieve very good classification accuracy and that nonlinear classification functions can be easily implemented by using kernels.

A strategy that is often used to separate these signals from background activity and noise is lowpass or bandpass filtering, optionally followed by downsampling.

The EEG is recorded at 2048 Hz sampling rate from thirty-two electrodes placed at the standard positions of the 10-20 international system.

Other examples for ERPs that can be used in BCIs are steady-state visual evoked potentialss (SSVEPs) and motorrelated potentials (MRPs).

The assumption underlying the application of ICA to EEG signals is that the signals measured on the scalp are a linear and instantaneous mixture of signals from independent sources in the cortex, deeper brain structures, and noise [18].

A drawback is however, that training SVMs is computationally complex because regularization constants and kernel parameters are typically estimated with a cross-validation procedure.

The main advantages of FDA are that it is a computationally and conceptually simple method and that very good classification accuracy can be achieved.

Besides the use for the EEG signals P300, SCP, and MRP, time domain features are also used in BCI systems based on neuronal ensemble activity.

Through a Bayesian analysis the degree of regularization can be estimated automatically and quickly from training data without the need for time consuming cross-validation.

The idea underlying research on neuromotor prostheses is to use a BCI for controlling movement of limbs and to restore motor function in tetraplegics or amputees.

One approach to overcome these problems, is to develop machine learning algorithms, with which subjects can immediately start using a BCI, without training.

Neuronal ensemble activity can thus be employed as neurophysiological signal in BCIs, in particular in BCIs using microelectrode arrays [12].

Because steering a wheelchair is a complex task and becausewheelchair control has to be extremely reliable, the possible movements of the wheelchair are strongly constrained in current prototype systems.

A second issue is that the loss function used in the SVM is designed for problems in which only binary yes/no outputs are needed.

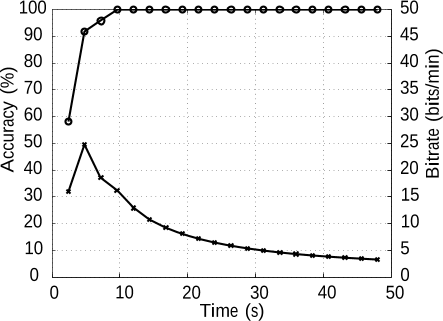

While due to fatigue or concentration problems not all ablebodied subjects achieved 100% classification accuracy, the bitrates for the able-bodied subjects were in general higher than those of the disabled subjects.

The types of signals resulting from concentration on mental tasks together with the corresponding BCI paradigms are described in subsections IIB, II-C, and II-D.ERPs are stereotyped, spatio-temporal patterns of brain activity, occurring time-locked to an event, for example after presentation of a stimulus, before execution of a movement, or after the detection of a novel stimulus.

algorithms that can detect if the user wants to communicate via the BCI or is engaged in other activity have to be developed.

For three of the other four disabled subjects tested in their study 100% classification accuracy was also achieved and the maximal bitrate varied between 9 and 19 bits/min.