read more

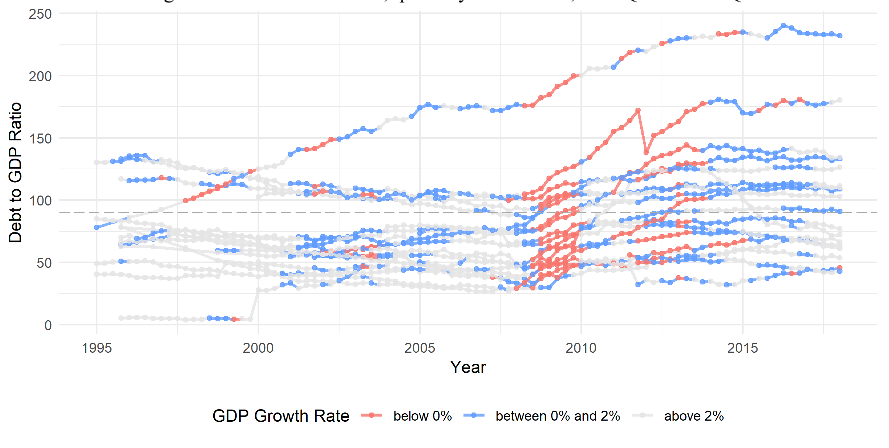

When analysing the inter-temporal linkage between growth and debt, their time series analysis provides crucial evidence on the much debated possibility that growth can be endogenous on the level of external public debt. The authors build this argument, firstly, on the observations that the times series plots for growth in GDP, over the last six decades, reveal a downward trend over the sample ; a fact which could be the actual explanation for any negative correlation between debt and growth. Thirdly, it seems that periods of low growth tend to be clustered around common time periods for many countries and not bound to country samples displaying particularly high levels of debt, thereby offering further support for reverse causality. In addressing the question of the existence of a debt threshold, the authors find no evidence that countries will experience significant reductions in GDP growth after surpassing a certain percentage of the debt-to-GDP ratio.

An immediate issue arising is the obvious endogeneity problem resulting in an estimation bias of(2)which the authors derive in Appendix C.

Particularly for a set of homogeneous and strongly interconnected entities, cross-sectional dependence may severely bias estimation results.

In a sample of 16 OECD countries spanning 30 years Puente-Ajovín and Sanso-Navarro (2015) apply a panel bootstrap Granger causality test developed by Kónya (2006) which accounts for cross-country heterogeneity as well as cross-sectional dependence.

Using a dynamic Common Correlated Effects (CCE) Mean Group estimator which allows for varying country-level coefficients they find no empirical evidence of a common cross-country debt threshold.

Whilst the authors acknowledge the wider scope of the literature, the purpose of this study is to concentrate on the empirical post-crisis strand which has the ‘debt-threshold’ hypothesis at its core.

What makes the threshold argument problematic in the eyes of the authors of this study is that through their ad-hoc selection rule, Reinhart et al. (2012) identify 26 debt-overhang periods for only 13 out of their sample of 22 advanced countries and furthermore note that ‘[...] many debt overhangs result from costly wars.

A straight-forward way common within the literature to address this issue is by treating both GR and D as endogenous by means of a vector autoregressive (VAR) model of the form(3a)(3b)where (pGR, pGR) denotes the selected lag length for the endogenous variables.

Another study which analyses a Granger causal relationship is Irons and Bivens (2010) who study the debtgrowth nexus for the case of the USA and fail to reject non-Granger causality going from debt to growth but finds significant evidence of a reverse causality link from growth to debt.

they report that the association of debt and growth tends to weaken for higher levels of debt, particularly when controlling for peer country growth rates.

As discussed before, Baum et al. (2013) find evidence of a considerable increase in the significant debt threshold (from 66 to 72 and 96 percent for the non-dynamic and dynamic panel respectively) if the crisis years 2008 to 2010 are added to the analysis.

Checherita-Westphal and Rother (2012) also employ endogenous instruments tocombat the challenges of endogeneity by means of a GMM estimation framework.

More precisely, their ‘[...] main result is that whereas the link between growth and debt seems relatively weak at ‘normal’ debt levels, median growth rates for countries with public debt over roughly 90 percent of GDP are about one percent lower than otherwise’ (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2010, p. 573).