Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

593 citations

556 citations

453 citations

380 citations

372 citations

[...]

14,563 citations

[...]

13,984 citations

10,005 citations

7,208 citations

The authors undertake a systematic empirical study to evaluate the role of the alternative explanations behind the “ Lucas Paradox, ” which include differences in fundamentals and capital market imperfections. Capital flows began to increase starting in the 1960s, and further expanded in the 1970s after the demise of the Bretton Woods system. Their results suggest that policies aimed at strengthening the protection of property rights, reducing corruption, increasing government stability, bureaucratic quality and law and order should be at the top of the list of policy makers seeking to increase capital inflows to poor countries.

In addition, because of missing portfolio data (some countries tend not to receive portfolio flows, in part due to lack of functioning stock markets), the authors prefer to use total foreign equity flows in the analysis, which is the sum of inflows of direct and portfolio equity investment.

The authors use Arcview software to obtain latitude and longitude of each capital city and calculate the great arc distance between each pair.

Lucas finds that accounting for the differences in human capital quality across countries significantly reduces the return differentials and considering the role of human capital externalities eliminates the return differentials.

They argue the following: “[T]he fact that so many poor countries are in default on their debts, that so little funds are channeled through equity, and that overall private lending rises more than proportionately with wealth, all strongly support the view that political risk is the main reason why the authors do not see more capital flows to developing countries.

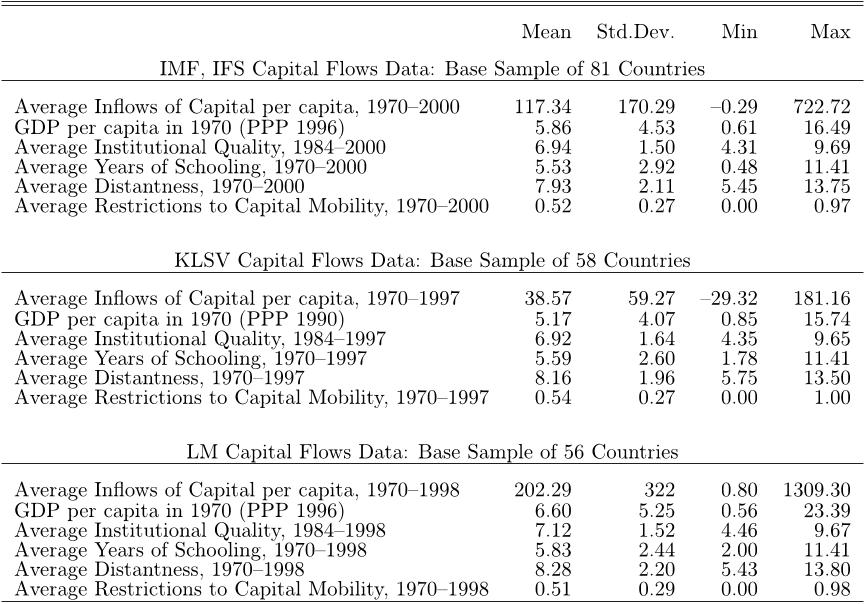

GDP per capita in 1970 varies between 500 PPP U.S. dollars to 23,000 PPP U.S. dollars; and the most educated country has 11 years of schooling as opposed to 0 in the least educated country.

7The International Financial Statistics (IFS) issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is the standard data source for annual capital inflows.

The authors can model the effect of these distortive government policies by assuming that governments tax capital’s return at a rate τ , which differs across countries.

In general, under asymmetric information, the main implications of the neoclassical model regarding the capital flows tend not to hold.

Multinational companies such as Metro AG, PSA Peugeot Citroen, Vodafone PLC, and France Telekom are increasing their FDI to Turkey, arguing that the investor protection and overall investment climate improved considerably as a result of these reforms.

The authors use Hansen’s overidentification test (J-test) to check the null hypothesis41This is similar to the first stage regression in Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001), where they regress the average risk of expropriation (which is one the components of their index of institutions) on log settler mortality.