read more

As far as ceramics are concerned, size variation was used as one criterion to distinguish three categories of full-size, small size, and miniature vessels.

Some of the ways that children have been made visible by archaeologists is through representation, bioarchaeological data, and the identification of some miniature objects as toys.

The majority of vessels are hand-modeled using the pinching technique, which is well known as one of the simplest techniques of shaping ceramics and one used by children beginning to learn the craft.

Several ethnographic studies in South Asia focusing on ceramic production at the household level concentrate on the male crafter with women and children performing the subordinate but necessary tasks such as clay procurement and preparation, decorating finished vessels, and so forth.

The rim diameters of bowls, derived by averaging the length and breadth measurements, range from a maximum of 37.6 mm to a minimum of 16.6 mm.

spring 201086children as novice craftersOne of the promising areas for studying children in archaeology has been through craft working.

When most ceramic production, for example, takes place within the house, one sees the involvement of the potter’s family, including women and young children, who help with the decoration of unglazed ware and other tasks such as preparing clay, carrying, and shifting vessels at various stages of the manufacturing process (Kamp 2002 : 28; Rye and Evans 1990 : 168).

According to Gupta (1996 : 22), copper punch-marked coins are found from the post-Mauryan period from the Magadh-Anga, Mathura, and Mewar regions.

Kamp shows that with age, because the surface area of the finger expands, this can be measured through ridge breadth measurements, defined as ‘‘the width of a single ridge and valley pair.’’

the molding of ceramic figurines is a technology that would have permitted crafters of various ages, including children, to participate in their production (Lopiparo 2006 : 169).

Dominant discourses; lived experiences: Studying the archaeology of children and childhood, in Children in Action: Perspectives on the Archaeology of Childhood: 115–122, ed. J. E. Baxter.

Dominant discourses; lived experiences: Studying the archaeology of children and childhood, in Children in Action: Perspectives on the Archaeology of Childhood: 115–122, ed. J. E. Baxter.

A specific case study on apprenticeship in ceramic manufacture focusing on the stages by which small boys began to use the wheel for making ceramics found that boys began learning between the ages of eight and eleven, due to the physiological reason of being able to reach the center of the wheel by then.

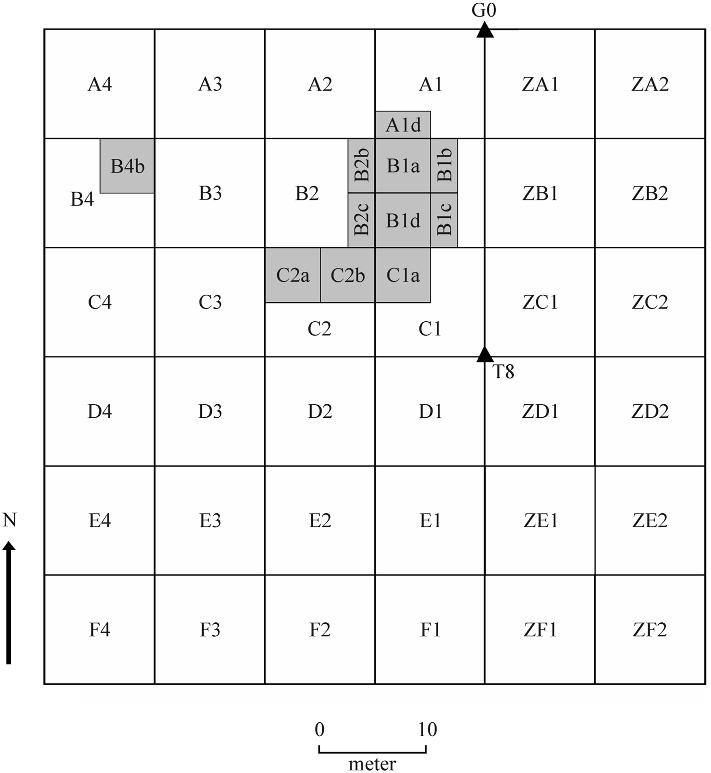

As the area under the present village was not going to be excavated, only the unoccupied parts of the site were gridded on a 10 10 m grid.

spring 2010106As mentioned earlier, 19 lumps were found that have been suggested to represent initial stages of making vessels and objects.

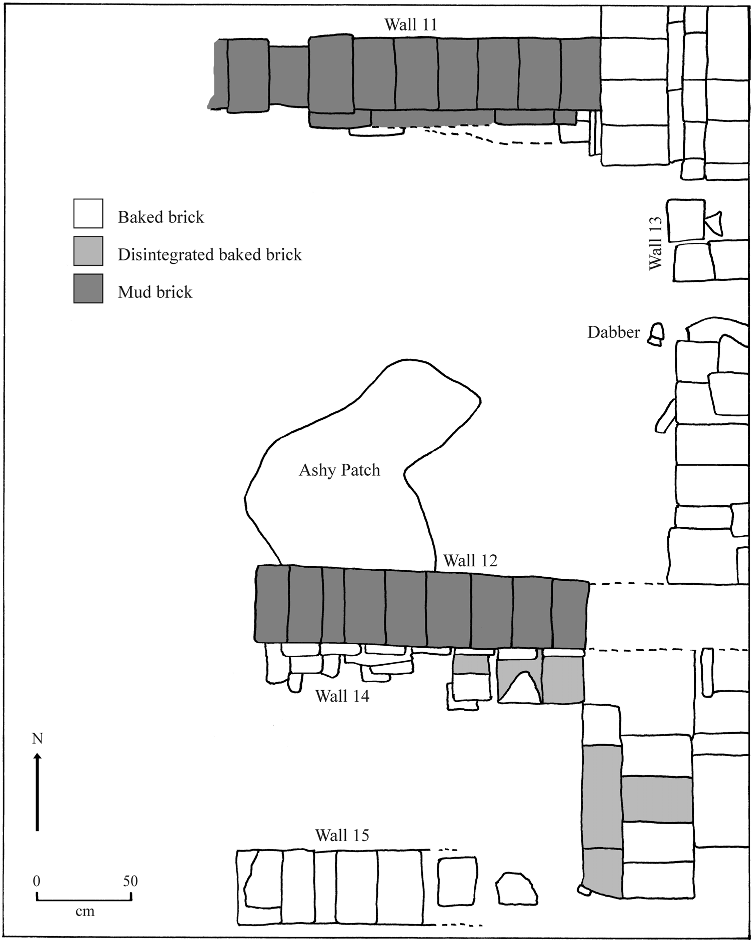

Of these, the western wall, Wall 8, 224 cm in length, extended south to the end of the subsquare, while of the eastern wall (Wall 9), only three bricks were extant.