read more

The non-surgical treatment options [9, 20, 34, 46, 67] consist basically of non-steroid anti-inflammatory medication, muscle relaxants, pain medication, muscle exercises, swimming and occasionally gentle traction, while avoiding manipulations and physical activation that may increase the pain.

depending on the cause of the curve, the lumbosacral junction usually is degenerated: disc space narrowing, facet joint arthritis, vertebral obliquity and possibly rotational deformity and sometimes even spontaneous fusion of L5 to S1 might be a consequence of a lumbosacral transitional anomaly or a progressed degeneration.

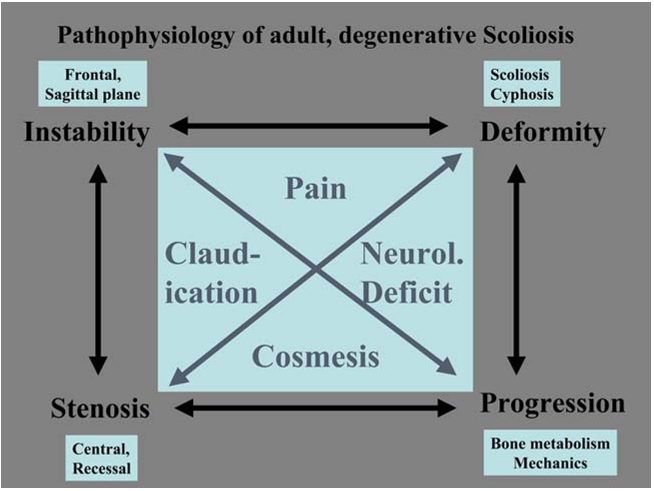

The asymmetric degeneration of the disc and/or the facet joints leads to an asymmetric loading of the spinal segment and consequently of a whole spinal area.

The second important symptom of adult degenerative scoliosis is radicular pain and claudication symptoms when standing or walking [57, 73].

As patients, who present themselves with significant clinical problems in the context of adult scoliosis, get older, minimal invasive procedures to address exactly the most relevant clinical problem may become more and more important, basically ignoring the overall deformity and degeneration of the spine.

The posterior pedicular systems nowadays allow a powerful manipulation, correction, and stabilization of the lumbar spine, as long as a proper posterior release precedes the corrective and stabilization procedure.

Whether the emerging dynamic fixation devices or even disc arthroplasty will be an option in the surgical treatment of adult degenerated scoliosis remains to be considered as more experience is acquired with that kind of implant.

The sagittal deformity is almost always exclusively a flat back syndrome or a loss of physiological lordosis and in extreme situations a real kyphosis.

This is the time when degenerative scoliosis may become increasingly symptomatic because the curve may progress due to the asymptomatic load on weakened vertebrae, which get more wedged and deformed.

When analyzed, regarding their overall daily activity by different questionnaires [50], most of these patients irrespective of age have improved in almost all categories of quality of life, and the use of regular pain medication is reduced substantially in more than 70% of these patients.

Keywords Adult scoliosis Æ Degenerative scoliosis Æ Spinal stenosis Æ Adult deformity Æ Secondary scoliosistherefore the main bulk of adult scoliosis.