read more

(A) Already in 2002, 266 municipalities, 70.5% of the municipalities of Sardinia, had presented at least one personalized plan in favour of residents with severe disabilities.

User led organizations supported families in designing their own plans, sustaining the relationship with social workers and personal assistants, influencing mass media conceived as a sounding board for requesting support to personalized plans.

The authors define individualized social service (ISS) as a top-down example of policy making, aimed at offering a standardized and specified provision of social services, which could be better defined as ‘customization’ of services.

Social workers have been asked to focus on their job, and personalization and co-designing strategies activated with users and family members.

Introduction European Welfare states are facing a growing demand for personalized social services, due to – among many reasons – the de-standardization and heterogeneity of individual needs (Valkenburg, 2007) which give room to the dramatic rise of new (Taylor-Gooby, 2005) and non-actuarial societal risks (Sabel, 2012): harms whose incidence is so unpredictable that it is impossible for those at risk to create an insurance pool sufficient to indemnify those who incur losses.

Userled organizations and unions defended the amount of social expenditure reserved for disability and long-term care because it gave them power to negotiate.

User-led organizations were pushed to accentuate their defensive and advocacy role to the detriment of their previous proactive and supportive role.

An assistant can work with a child in a family from 6 to 10 hours maximum per week, but for the rest of the hours the parents and other figures around the family have to take care of them.

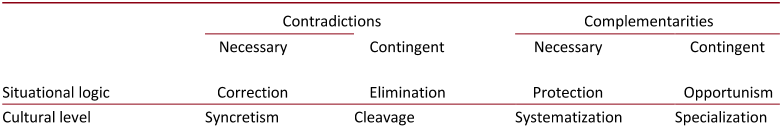

A new form of opportunistic behaviour is now developing, especially in some areas of Sardinia, where the pressure to have a household income in order to participate in consumption is very strong.

Without co-design and co-production of services, i.e. the inclusion and activation of users and clients into the service, personalization became mere (standardized) individualization.

(Interview no. 9)(D) The care system changed in many ways: the funding strategy moved from a mutual public-private arrangement, to direct families’ reimbursements (according to eligible costs of personalized plans); the topic of social policies changed as well, from standard treatments based on experts’ knowledge to care services chosen and controlled by users.

Governance is more pluralistic when it is open to the largest number of actors: users and their families, users’ associations, for-profit or non-profit service providers, public administrations.

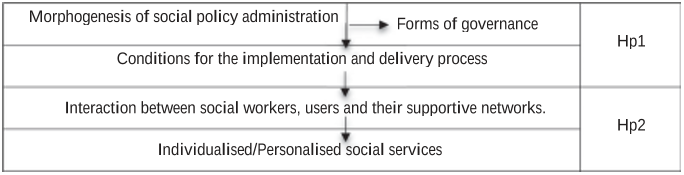

In identifying the development of the policy governance and its street-level functioning, the authors have observed a morphogenetic cycle composed by four different phases (Table 4): (1) the period since the Regional enforcement of the law 1682/98 (before 2000); (2) the period covering the start-up and the institutionalization of services (between 2000 and4.