read more

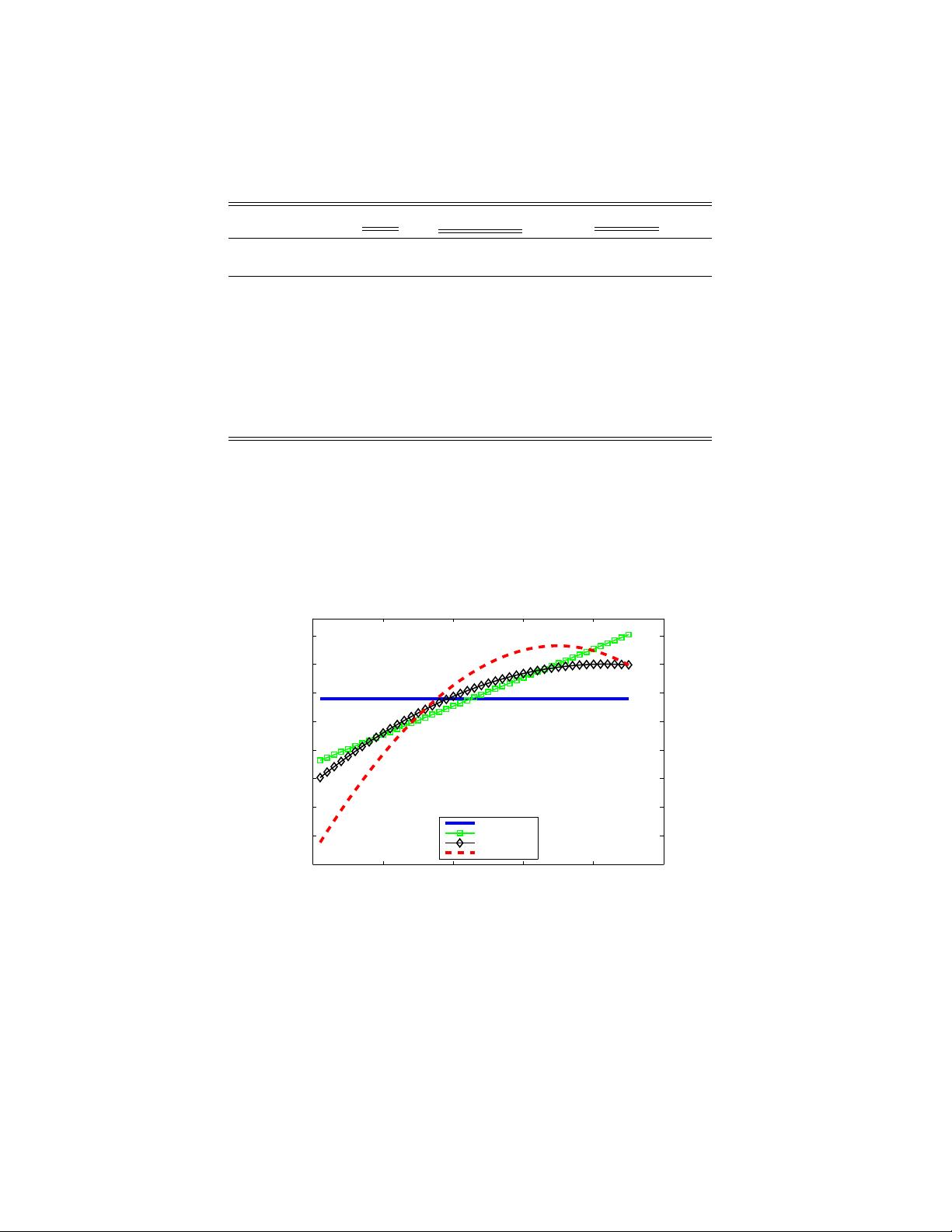

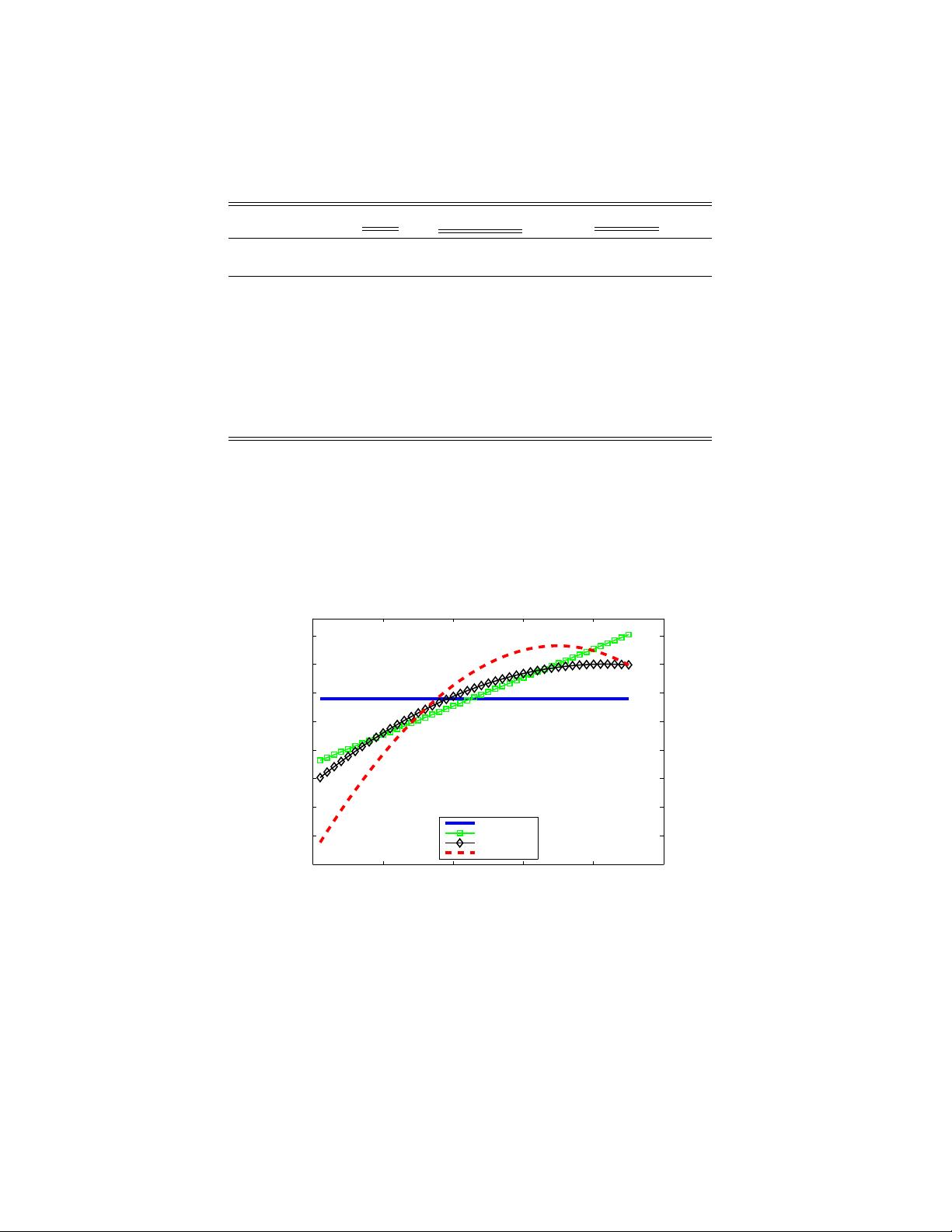

If the tax function is a second-degree polynomial then the tax distortion also increases but a smaller rate for older households.

1In the benchmark model the (heterogeneity in) labor supply elasticity depends mostly on the distribution of reservation wages and not on the value θ (see Hansen (1985), Rogerson (1988), and Chang and Kim (2006)).

The value function for a household employing the female worker is:V {NE,E} zj (a,x,κ,E−1) = maxc,a′,hf{ log(c) + ψmj (1− hm)1−θ1− θ + ψfj(1− hf )1−θ1− θ − ζ(Ef−1)+βsj+1 ∑ xm′ ∑ xf ′ Γxmx′mΓxfx′f ∗[ (1− λm) 1− p ∑s={2,3}psV 1z(j+1)(a ′,x′,κs,E) +λm 1− p ∑s={2,3}psV {NE,NE} z(j+1) (a ′,x′,κs,E)] (1)s.t. hf = 0 (2)(1+τc)c+a ′ = (1−τss)W −TL(W ; S)+(1+r(1−τk))(a+Tr) (3)E = {u, e} (4)The value function for a household with no earners is:V {NE,NE} zj (a,x,κ,E−1) = maxc,a′{ log(c) + ψmj (1− hm)1−θ1− θ + ψfj(1− hf )1−θ1− θ+βsj+1 ∑ xm′ ∑ xf ′ Γxmx′mΓxfx′f V 2 z(j+1)(a ′,x′,κ0,E)] (5)s.t. hm = 0, hf = 0 (6)(1+τc)c+a ′ = (1+r(1−τk))(a+Tr) (7)E = {u, u} (8)