NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS CYCLES

Pedro Brinca

V. V. Chari

Patrick J. Kehoe

Ellen McGrattan

Working Paper 22663

http://www.nber.org/papers/w22663

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

September 2016

We thank Peter Klenow for useful comments and Francesca Loria for excellent research

assistance. Chari and Kehoe thank the National Science Foundation for financial support. Pedro

Brinca is grateful for financial support from the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation,

grants number SFRH/BPD/99758/2014, UID/ECO/00124/2013, and UID/ECO/00145/2013. The

views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve

Bank of Minneapolis, the Federal Reserve System, or the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2016 by Pedro Brinca, V. V. Chari, Patrick J. Kehoe, and Ellen McGrattan. All rights reserved.

Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission

provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.

Accounting for Business Cycles

Pedro Brinca, V. V. Chari, Patrick J. Kehoe, and Ellen McGrattan

NBER Working Paper No. 22663

September 2016

JEL No. E00,E12,E13,E22,E24,E44

ABSTRACT

We elaborate on the business cycle accounting method proposed by Chari, Kehoe, and McGrattan

(2007), clear up some misconceptions about the method, and then apply it to compare the Great

Recession across OECD countries as well as to the recessions of the 1980s in these countries. We

have four main findings. First, with the notable exception of the United States, Spain, Ireland, and

Iceland, the Great Recession was driven primarily by the efficiency wedge. Second, in the Great

Recession, the labor wedge plays a dominant role only in the United States, and the investment

wedge plays a dominant role in Spain, Ireland, and Iceland. Third, in the recessions of the 1980s,

the labor wedge played a dominant role only in France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and New

Zealand. Finally, overall in the Great Recession the efficiency wedge played a more important

role and the investment wedge played a less important role than they did in the recessions of the

1980s.

Pedro Brinca

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

San Domenico di Fiesole

Italy

pedro.ms.brinca@gmail.com

V. V. Chari

Department of Economics

University of Minnesota

1035 Heller Hall

271 - 19th Avenue South

Minneapolis, MN 55455

and NBER

varadarajanvchari@gmail.com

Patrick J. Kehoe

Department of Economics

Stanford University

579 Serra Mall

Stanford, CA 94305

and NBER

patrickjameskehoe@gmail.com

Ellen McGrattan

Department of Economics

University of Minnesota

4-101 Hanson Hall

1925 4th St S

Minneapolis, MN 55455

and NBER

erm@umn.edu

In this paper we elaborate on the business cycle accounting method proposed by Chari,

Kehoe, and McGrattan (2007), henceforth CKM, clear up some misconceptions about the

method, and then apply it to compare the Great Recession across OECD countries as well

as to the recessions of the 1980s in these countries. The goal of the method is to help guide

researchers’choices about where to introduce frictions into their detailed quantitative models

in order to allow the models to generate business cycle ‡uctuations similar to those in the

data.

The method has two components: an equivalence result and an accounting procedure.

The equivalence result is that a large class of models, including models with various types of

frictions, is equivalent to a prototype model with various types of time-varying wedges that

distort the equilibrium decisions of agents operating in otherwise competitive markets. At

face value, these wedges look like time-varying productivity, labor income taxes, investment

taxes, and government consumption. We labeled these wedges e¢ ciency wedges, labor wedges,

investment wedges, and government consumption wedges.

The accounting procedure also has two components. It begins by measuring the wedges,

using data together with the equilibrium conditions of a prototype model. The measured

wedge values are then fed back into the prototype model, one at a time and in combinations,

in order to assess how much of the observed movements of output, labor, and investment can

be attributed to each wedge, separately and in combinations.

Here we use this method to study the Great Recession in OECD countries. We also

compare this recession with the recessions of the early 1980s. While the exact timing of

the recessions of the early 1980s di¤ers across countries in our OECD sample, most of the

countries had a recession between 1980 and 1984. Throughout we refer to the recessions of

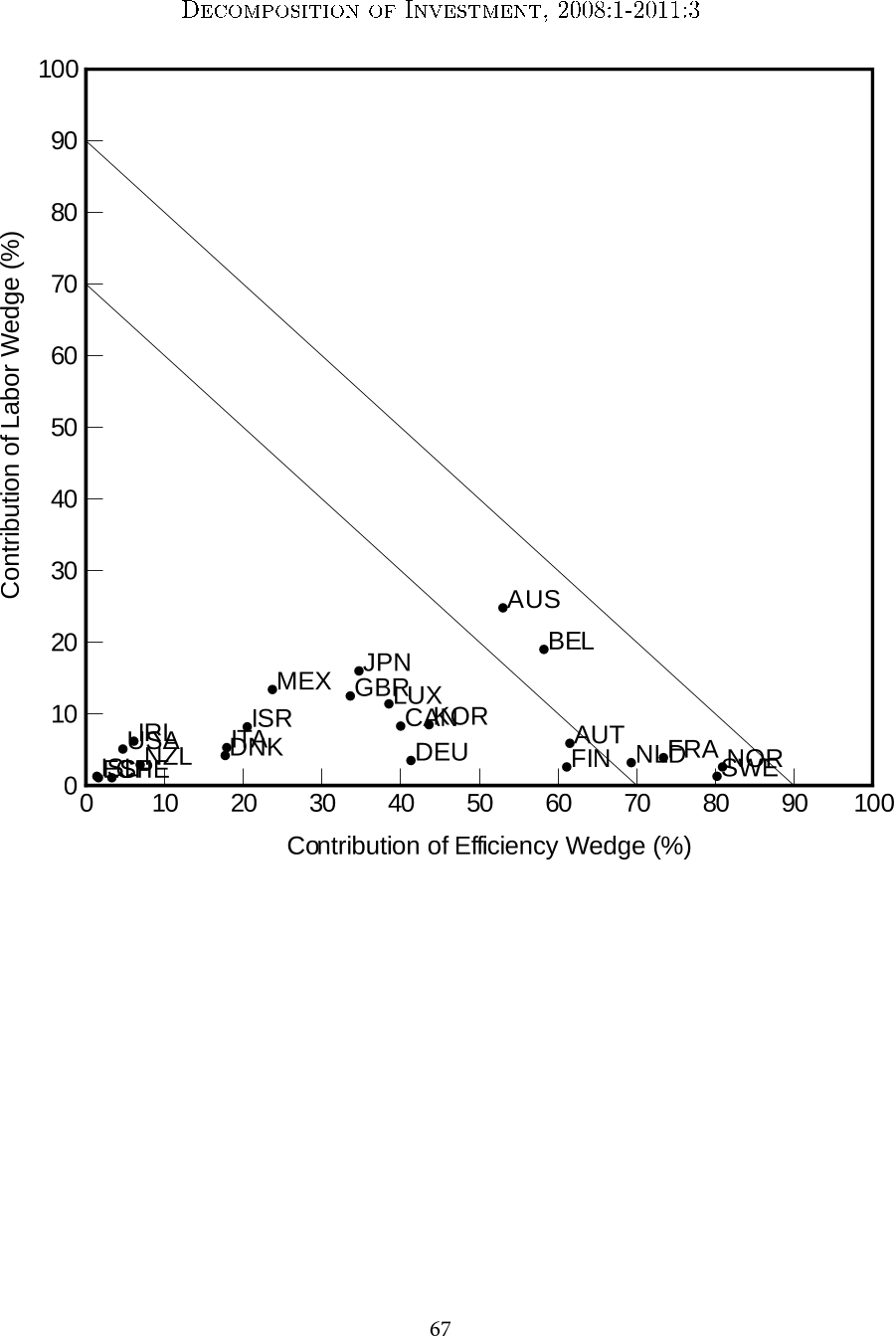

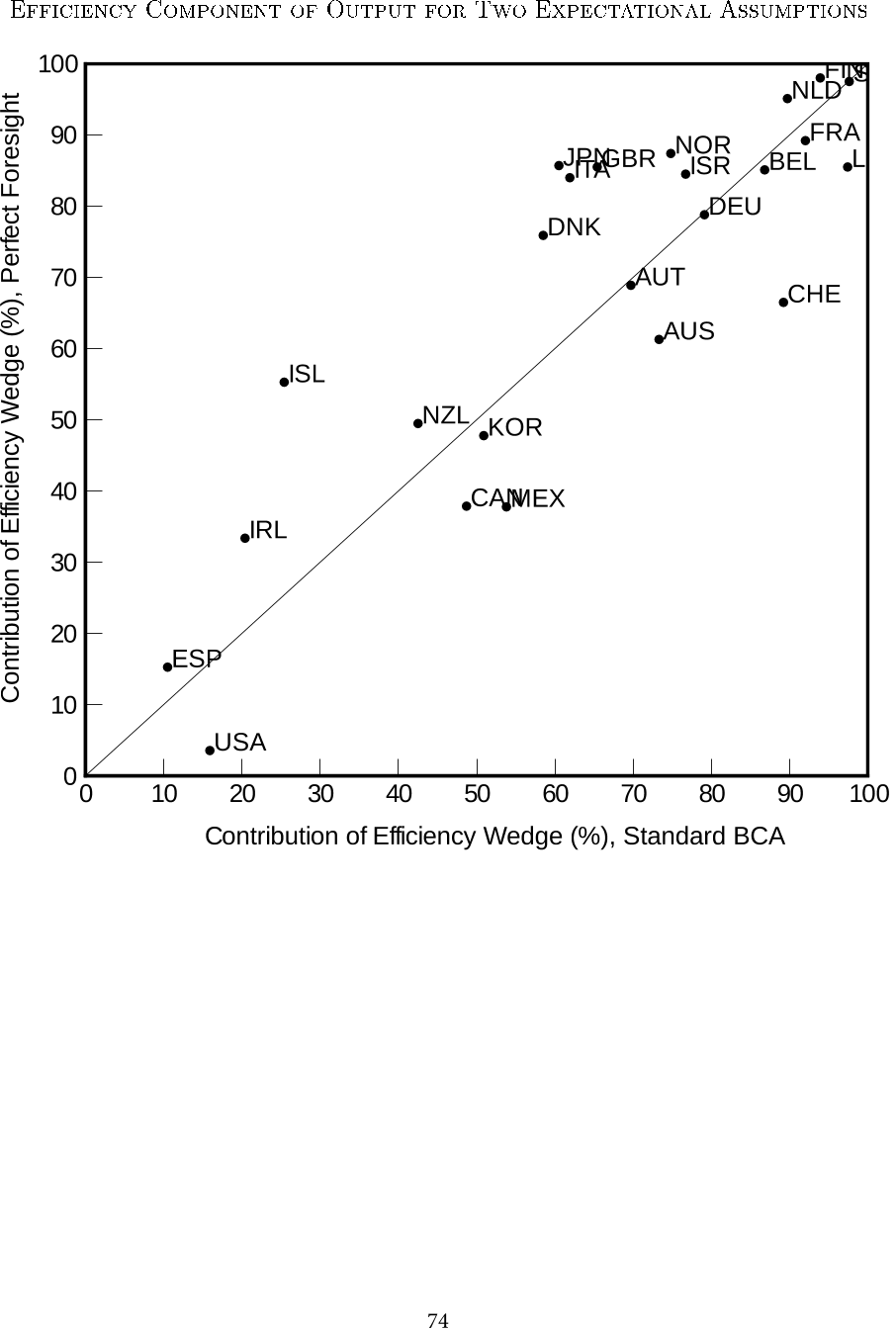

the early 1980s as the 1982 recession. We have four main …ndings. First, with the notable

exception of the United States, Spain, Ireland, and Iceland, the Great Recession was driven

primarily by the e¢ ciency wedge. Second, in the Great Recession, the labor wedge plays a

dominant role only in the United States, and the investment wedge plays a dominant role in

Spain, Ireland, and Iceland. Third, in the recessions of the 1980s, the labor wedge played

a dominant role only in France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and New Zealand. Finally,

overall in the Great Recession the e¢ ciency wedge played a more important role and the

investment wedge played a less important role than they did in the recessions of the 1980s.

We now turn to elaborating on the equivalence results in CKM that link the four

wedges to detailed models. We begin by showing that a detailed economy with ‡uctuations

in investment-speci…c technological change similar to that in Greenwood, Hercowitz, and

Krusell (1997) maps into a prototype economy with investment wedges. This result makes

clear that investment wedges are by no means synonymous with …nancial frictions, a point

stressed by CKM.

We then consider an economy that blends elements of Kiyotaki and Moore (1997)

with that of Gertler and Kiyotaki (2009). The economy has a representative household

and heterogeneous banks that face collateral constraints. We show that such an economy

is equivalent to a prototype economy with investment wedges. This result makes clear that

some ways of modeling …nancial frictions do indeed show up as investment wedges.

Finally, we turn to an economy studied by Buera and Moll (2015) consisting of workers

and entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurs have access to heterogeneous production technologies

that are subject to shocks to collateral constraints. We follow Buera and Moll (2015) in

showing that this detailed economy is equivalent to a prototype model with a labor wedge,

an investment wedge, and an e¢ ciency wedge. This equivalence makes the same point as does

the input-…nancing friction economy in CKM, namely, that other ways of modeling …nancial

frictions can show up as e¢ ciency wedges and labor wedges.

The point of the three examples just discussed is to help clarify how the pattern of

wedges in the data can help researchers narrow down the class of models they are considering.

If, for example, most of the ‡uctuations are driven by the e¢ ciency and labor wedges in the

data, then of the three models just considered, the third one is more promising than the …rst

two.

We then turn to models with search frictions. We use these models to make an

important point. Researchers should choose the baseline prototype economy that provides

the most insights for the research program of interest. In particular, when the detailed

economies of interest are su¢ ciently di¤erent from the one-sector growth model, it is often

more instructive to adjust the prototype model so that the version of it without wedges

corresponds to the planning problem for the class of models at hand. For example, when we

2

map the model with e¢ cient search into the one-sector model, that model does have e¢ ciency

and labor wedges, but if we map it into a new prototype model with two capital-like variables,

physical capital and the stock of employed workers, the new prototype model has no wedges.

We then consider a search model with an ine¢ cient equilibrium. When we map this

model into the new prototype model with two capital-like variables, then the prototype model

has only labor wedges. But if we map it into the original prototype model, it has e¢ ciency

wedges and (complicated) labor wedges. These …ndings reinforce the point that it is often

more instructive to adjust the prototype model so that the version of it without wedges

corresponds to the planning problem for the class of models at hand.

Taken together, these equivalence results help clear up some common misconceptions.

The …rst misconception is that e¢ ciency wedges in a prototype model can only come from

technology sho cks in a detailed model. In our judgment, by far the least interesting inter-

pretation of e¢ ciency wedges is as narrowly interpreted shocks to the blueprints governing

individual …rm production functions. More interesting interpretations rest on frictions that

deliver such high-frequency movements in this wedge. For example, the input-…nancing fric-

tion model in CKM shows how …nancial frictions in a detailed model can manifest themselves

as e¢ ciency wedges. Indeed, we think that exploring detailed models in which the sudden

drops in e¢ ciency wedges experienced in recessions come from frictions such as input-…nancing

frictions is more promising than blaming these drops on abrupt negative shocks to blueprints

for technologies. The second misconception is that labor wedges in a prototype model arise

solely from frictions in labor markets in detailed economies. The Buera-Moll economy makes

clear that this view is incorrect. The third misconception is that investment wedges arise

solely due to …nancial frictions. Clearly, the detailed model with investment-speci…c techni-

cal change shows that this view is also incorrect.

We turn now to describing our procedure. This procedure is designed to answer

questions of the following kind: How much would output ‡uctuate if the only wedge that

‡uctuated is the e¢ ciency wedge and the probability distribution of the e¢ ciency wedge is

the same as in the prototype economy? If the wedges were independent at all leads and

lags, the procedure can be implemented in a straightforward manner by letting only, say, the

e¢ ciency wedge ‡uctuate and setting all other wedges to constants. In the data, the wedges

3