1

Comparing alternative methods to estimate

gravity models of bilateral trade

Estrella Gómez Herrera. Department of Economic Theory, University of Granada,

Granada, Spain (e-mail: estrellagh@ugr.es)

Abstract. The gravity equation has been traditionally used to predict trade flows across countries.

However, several problems related with its empirical application still remain unsolved. The unobserved

heterogeneity, the presence of heteroskedasticity in trade data or the existence of zero flows, which make

the estimation of the logarithm unfeasible, are some of them. This paper provides a survey of the most

recent literature concerning the specification and estimation methods of this equation. For a dataset

covering 80% of world trade, the most widely extended estimators are compared, showing that the

Heckman sample selection model performs better overall for the specification of gravity equation

selected.

Keywords International trade, gravity model, estimation methods

JEL Classification C13, C33, F10

1. Introduction

The gravity model of trade, which was originally inspired by Newton’s gravity

equation, is based on the idea that trade volumes between two countries depend on their

sizes in relation to the distance between them. In the last fifty years, this model has been

widely used to predict trade flows.

The gravity equation appears to be highly effective at this point as proven at a

very early date by the works of Linnemann (1966) and Leamer and Stern (1971).

However, several controversies have arisen regarding the model. The theoretical

framework was put into doubt and afterwards justified by Bergstrand (1989) for the

factorial model, Deardorff (1998) for the Hecksher-Ohlin model, Anderson (1979) for

goods differentiated according to their origin, and Helpman et al. (2008) in the context

of firm heterogeneity. After some additional discussions concerning its specification in

the nineties, the debate has now turned to the performance of different estimation

techniques. New estimation problems concerning the validity of the log linearisation

process of the gravity equation in the presence of heteroskedasticity and the loss of

information due to the existence of zero trade flows have been recently explored.

Traditionally, the multiplicative gravity model has been linearised and estimated

using OLS assuming that the variance of the error is constant across observations

(homoskedasticity), or using panel techniques assuming that the error is constant across

countries or country-pairs. However, as pointed out by Santos Silva and Tenreyro

(2006), in the presence of heteroskedasticity, OLS estimation may not be consistent and

nonlinear estimators should be used. Another challenge described in the literature

concerns the zero values. Helpman et al. (2008) propose a theoretical foundation based

on a model with heterogeneity of firms à la Melitz (2003) and an adapted Heckman

procedure to predict trade taking into account these features. Recently, the works of

Burger et al. (2009), Martin and Pham (2008), Martínez-Zarzoso et al. (2007),

2

Siliverstovs and Schumacher (2009) and Westerlund and Wilhelmsson (2009) have

obtained divergent results when comparing alternative estimation methods.

This paper reviews most estimation methods and problems and provides a survey

of the literature related to this topic. The performance of several linear and nonlinear

estimators is compared using a three-dimensional (i, j, t) dataset, analysing the most

relevant properties of each one. To this end, a gravity equation based on Anderson and

van Wincoop’s (2003) theoretical model is used. Using this equation, the fit of different

estimation procedures applied to a large dataset of bilateral exports for 80 countries

(80% of world trade) over the 1980-2008 period is discussed. The fit of each method is

compared through different measures, revealing the main advantages and disadvantages

of each one. It is shown that methods that do not properly treat the presence of zero

flows on data exhibit noticeably worse performance than others. On the other hand,

nonlinear estimators show more accurate results and are robust to the presence of

heteroskedasticity in data. Overall, the Heckman sample selection model is revealed to

be the estimator with the most desirable properties, confirming the existence of sample

selection bias and the need to take into account the first step (probability of exporting)

to avoid the inconsistent estimation of gravity parameters.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The next section briefly reviews the

different theoretical foundations of the gravity equation to justify the election of the

empirical specification of the gravity equation chosen. Section 3 compares in detail the

different estimation methods available in the gravity literature. In Section 4, data are

presented and the results of different estimations methods are discussed and compared

to different criteria. Conclusions are drawn in Section 5. The figures and tables are

provided in the Appendix.

2. The gravity equation

The theoretical foundation of the gravity equation appeared seventeen years after its

empirical specification. The first article providing a microfoundation of this equation

was Anderson (1979) and was based on the Armington assumption of specialisation of

each nation in the production of only one good. Bergstrand (1985) initially supported

this hypothesis, completing the theoretical foundation with a more detailed explanation

of the supply side of economies and the inclusion of prices in the equation.

A few years later, a new wave of developments came with what has been called “the

new trade theory”. The main improvement was the replacement of the assumption of

product differentiation by country of origin by the assumption of product differentiation

among producing firms. In this line, Bergstrand (1990) provided a foundation based on

Dixit and Stiglitz’s monopolistic competition assumption. In addition, he generalised

the model by introducing prices and incorporating the Linder hypothesis. Helpman

(1987) also derived a foundation relying on the assumption of increasing returns to scale

where products were differentiated by firms, not only by country, and firms were

monopolistically competitive. However, some years later Deardoff (1998) asserted that

the gravity equation could be derived from standard trade theories, conciliating both the

old and the new theories.

Later on, the “new new trade theory” insisted on the heterogeneity of firms regarding

their exporting behaviour (Melitz 2003), thereby giving a theoretical foundation for the

presence of zero trade flows in data. In this line, Helpman et al. (2008) generalised the

empirical gravity equation by developing a two-stage estimation procedure that takes

into account extensive and intensive margins of trade. They showed that the incorrect

3

treatment of zero flows may lead to biased estimates and developed a complete

framework to provide a rationale for the existence of these flows.

Regarding the specification, Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) propose an augmented

version of the Anderson (1979) model based on the assumption of differentiation of

goods according to place of origin. Their main contribution is the inclusion of

multilateral resistance terms for the importer and the exporter that proxy for the

existence of unobserved trade barriers. This model is interesting overall to the extent

that the discussion of the multilateral resistance may matter for heteroskedasticity

considerations. In this model, countries are representative agents that export and import

goods. Goods are differentiated by place of origin and each country is specialised in the

production of only one good. Preferences are identical, homothetic and approximated by

a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) function.

The linear gravity equation estimated by Anderson and van Wincoop is as follows:

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

ijjiijijjiij

εPσPσbσdρσyykX +ln-1+ln-1+ln-1+ln-1+ln+ln+=ln

(1)

where X

ij

is the nominal value of exports from i to j; k is a positive constant, y

i

and y

j

are

the nominal income of each country, generally proxied by its GDP, and d

ij

is a measure

of the bilateral distance between i and j, which are introduced to proxy for transport

costs. b

ij

is a dummy variable that takes value one if two countries share a border.

Finally, the variables P

i

and P

j

are the multilateral resistance terms and are defined as a

function of each country’s full set of bilateral trade resistance terms. The variable of

interest for Anderson and van Wincoop is b

ij

since their objective is to estimate the trade

effect of national borders. They apply their equation to regional data.

The multilateral price indices (P

i

and P

j

) are not observed and should be estimated.

Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) use the observed variables in their model (distances,

borders, and income shares) to obtain the multilateral trade resistance terms. Assuming

symmetric trade costs, using 41 goods market-equilibrium conditions

1

and a trade cost

function defined in terms of

observables, they obtain the P

i

and P

j

terms. Although they

argue that this method is more efficient than any other, it is highly data consuming and

has not been frequently used by other authors.

An alternative solution is to include a remoteness variable to proxy for these multilateral

trade resistance indexes:

∑

=

j

ROWj

ij

i

yy

d

Rm

)(

(2)

where the numerator would be the bilateral distance between two countries, and the

denominator would be the share of each country’s GDP in the rest of the world’s GDP.

Head and Mayer's (2000) remoteness variable describes the full range of potential

suppliers to a given importer, taking into account their size, distance and relevant costs

of crossing the border. Wei (1996), Wolf (1997), and Helliwell (1996) provide other

examples of regressions including a remoteness variable. Alternatively, Feenstra (2002)

proposes introducing importer and exporter fixed effects to account for the specific

country multilateral resistance term. The coefficient of the dummies for the importer

1

Their sample contains the same 30 US states and 10 Canadian provinces that McCallum

(1995) includes. There are 20 additional states, plus Columbia, which they aggregate into one.

Hence, they finally have 41 equations.

4

and the exporter should reflect the multilateral resistance for each country. Several

studies using this approach are described in the Appendix (Table A1). Finally, Baier and

Bergstrand (2009) suggest generating a linear approximation of the P

i

and P

j

terms by

means of a first-order Taylor series expansion.

Concerning the proxy for supply and demand sizes, the common practice is to use

importer’s and exporter’s GDP correspondingly. In some cases GDP per capita is also

introduced as a proxy for capital-labour intensities.

Transaction costs are frequently proxied by geographical distance. However, it is

commonly accepted that geographical distance may be a poor approximation

2

. Thus,

this variable is often completed with other proxies for trade barriers specified as

indicator variables. For instance, adjacency takes value one if trade partners share a

common border, common language takes value one if both countries share a language,

colonial links captures the effect of having had a common coloniser or having been

colonised by another country in the past; religion takes value one when both countries

have the same religion; access to water takes value one if a country has access to water,

or Regional Trade Agreement (RTA) which assess the effect of RTAs on trade. All

these factors affect international trade via transaction costs and complete the

geographical distance variable in order to reflect the economic distance.

3. Summary of estimation methods

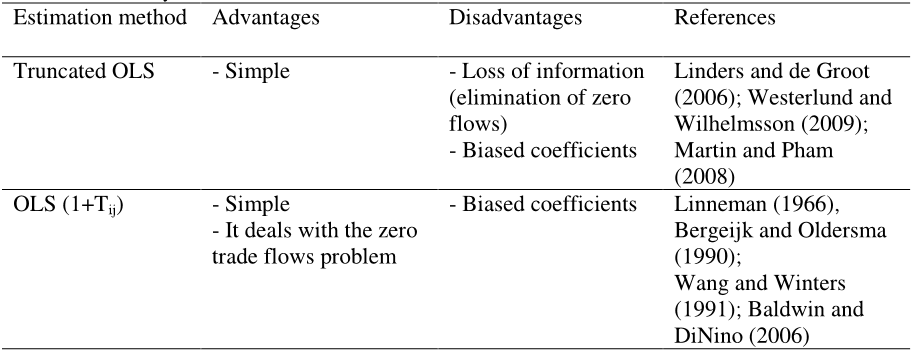

As mentioned above, interest in the last years has focused on estimation methods to

accurately predict trade flows. In this section, a brief summary of some of the most

important estimation methods as well as a revision of related empirical literature (Table

1) are presented.

3.1. Linear methods

Since the logarithm of zero is not defined, truncation and censoring methods have been

proposed in the literature to treat the problem of zero flows in data. However, these

procedures reduce efficiency due to the loss of information and may lead to biased

estimates due to the omission of data. Furthermore, as Westerlund and Wilhelmsson

(2009) point out, the elimination of trade flows when zeros are not randomly distributed

leads to sample selection bias.

In addition, a panel framework permits recognising how the relevant variables evolve

through time and identifying the specific time or country effects. Over the last years,

researchers such as Egger (2000), Rose and van Wincoop (2001), Mátyás (1998), Egger

and Pfaffermayr (2003, 2004), Glick and Rose (2002), Brun et al. (2002), and Melitz

(2007) have turned towards panel data

3

. Two main techniques are employed to fit data

depending on the a priori assumptions. The fixed effects estimator assumes the

existence of an unobserved heterogeneous component that is constant over time and

which affects each individual (pair of countries) of the panel in a different way. By

contrast, the random effects model imposes no correlation between the individual

effects and the regressors, implicitly assuming that the unobserved heterogeneous

2

In addition, there is no single opinion about how distance should be measured. The most

common measures are the great circle formula and the distance between the two principal cities.

See Wei (1996), Wolf (1997), and Head and Mayer (2000) for further information.

3

See Appendix A for further information.

5

component is strictly exogenous. Under the null hypothesis of zero correlation, the

random effects model is more efficient. However, if the null is rejected, only the fixed

effects model provides consistent estimators

4

.

3. 2. Nonlinear methods

As Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006) points out, the log-linearisation of the gravity

equation changes the property of the error term, thus leading to inefficient estimations

in the presence of heteroskedasticity. If the data are homoskedastic, the variance and the

expected value of the error term are constant but if they are not -as usually happens with

trade data-, the expected value of the error term is a function of the regressors. The

conditional distribution of the dependent variable is then altered and OLS estimation is

inconsistent. Heteroskedasticity does not affect the parameter estimates; the coefficients

should still be unbiased, but it biases the variance of the estimated parameters and,

consequently, the t-values cannot be trusted. Hence, the recent literature concerning

estimation techniques have opted to use nonlinear methods as well as two parts models

for estimating the gravity equation.

Among nonlinear estimation methods, the most frequently used are Nonlinear Least

Squares (NLS), Feasible Generalised Least Squares (FGLS), Heckman sample selection

model and Gamma and Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (GPML and PPML).

Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006) claim that NLS is inefficient since it gives more

weight to observations with larger variance and is not robust to heteroskedasticity.

Martínez-Zarzoso et al. (2007) propose Feasible Generalised Least Squares (FGLS) as

the most appropriate model if the exact form of heteroskedasticity in data is ignored

since it weighs the observations according to the square root of their variances and is

robust to any form of heteroskedasticity. Manning and Mullahy (2001) propose Gamma

Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (GPML). In this case the conditional variance of the

dependent variable is assumed to be proportional to its conditional mean. This estimator

therefore assigns less weight to observations with a larger conditional mean. Martínez-

Zarzoso et al. (2007) computes the performance of this estimator, finding it to be

adequate in the presence of heteroskedasticity, although it shows less accuracy when

zero trade values are present. Finally, Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (PPML) is

similar to GPML, but assigns the same weight to all observations. Santos Silva and

Tenreyro (2006) point out that this is the most natural procedure without any further

information on the pattern of heteroskedasticity.

In addition, two-step estimation methods have also been proposed to estimate the

gravity equation. This is the case of Heckman sample selection model. In the first step,

a Probit equation is estimated to define whether two countries trade or not and in a

second step, the expected values of the trade flows, conditional on that country trading,

are estimated using OLS. In order to identify the parameters on both equations, a

selection variable is required. This exclusion variable should affect only the decision

process; hence, it should be correlated with a country’s propensity to export but not with

its current levels of exports. Some examples in the literature are the common language

and common religion variable (Helpman et al. 2008), governance indicators of

regulatory quality (Shepotylo 2009), or the historical frequency of positive trade

4

The Hausman test provides a method for testing the adequacy of the random effect model. If

the null is rejected, the random effects model is not consistent. However, it is important to note

that this result does not imply that the fixed effect model is adequate.