WIDER Working Paper 2020/32

Measuring labour earnings inequality in post-

apartheid South Africa

Serena Merrino*

March 2020

* UNU-WIDER, Helsinki, Finland, and South African Reserve Bank, Pretoria, South Africa; sm147@soas.ac.uk

This study has been prepared within the UNU-WIDER project Southern Africa – Towards Inclusive Economic Development

(SA-TIED).

Copyright © UNU-WIDER 2020

Information and requests: publications@wider.unu.edu

ISSN 1798-7237 ISBN 978-92-9256-789-7

https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2020/789-7

Typescript prepared by Luke Finley.

The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research provides economic analysis and policy

advice with the aim of promoting sustainable and equitable development. The Institute began operations in 1985 in Helsinki,

Finland, as the first research and training centre of the United Nations University. Today it is a unique blend of think tank, research

institute, and UN agency—providing a range of services from policy advice to governments as well as freely available original

research.

The Institute is funded through income from an endowment fund with additional contributions to its work programme from

Finland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom as well as earmarked contributions for specific projects from a variety of donors.

Katajanokanlaituri 6 B, 00160 Helsinki, Finland

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United

Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

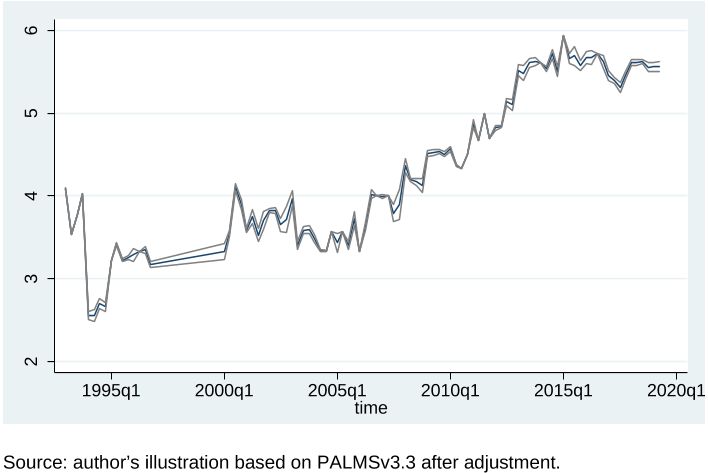

Abstract: This paper investigates the validity of household survey data published by Statistics

South Africa since 1993 and later integrated into the Post-Apartheid Labour Market Series

(PALMS). A series of statistical adjustments are proposed, compared, and applied to primary

data with the purpose of generating time-comparable, unbiased estimates, and accurate standard

errors of labour earnings inequality coefficients. In particular, corrections deal with

outliers and implausible data records, missing observations, bracket responses, breaks in the

series, under-reporting of high incomes, and quarterly frequency. This work lays the ground for

future research on the redistributive dynamics of economic policy in South Africa, which notably

suffers from the presence of spurious shifts in repeated cross-sections.

Key words: income inequality, distribution, heterogeneity, survey data, imputation

JEL classification: C31, D31, O15, R20

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Professor Laurence Harris for his mentorship, and to the

South African Reserve Bank, in the persons of Dr Chris Loewald and Dr Konstantin Makrelov,

for hosting my field research.

1

1 The Post-Apartheid Labour Market Series

Despite there being a rich literature examining cross-sectional inequality in South Africa, no

consensus has been reached on the quality of long-run time series. In effect, multiple generations

of household surveys have been produced since the end of the apartheid regime by local statistical

and research agencies—first and foremost the parastatal Statistics South Africa (Stats SA)—which

provide nationally representative micro-level information on the labour market.

1

Although today

these resources constitute an abundant pool of information, they were not originally designed for

dynamic analysis and do not allow for straightforward comparability and immediate use in

longitudinal studies. In other words, the nature of the data collected differs more or less

substantially in each survey wave because of differences in, for example, the sample design

instrument and definitions.

As a response to rising concerns over the validity of using distributional data to undertake time-

comparative exercises, the University of Cape Town’s DataFirst initiated a study of successive

labour market cross-sections and integrated them into a single longitudinal data set. This project

produced the so-called Post-Apartheid Labour Market Series (PALMS): a stacked cross-section

consisting of a harmonized compilation of four household surveys

2

conducted after 1993 and

focused on socioeconomic topics (Kerr et al. 2013). Specifically, PALMS consists of:

• The 1993 Project for Statistics on Living Standards and Development (PSLSD); Southern

Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU UCT); annual.

• The 1994–99 October Household Surveys (OHS); Stats SA; annual.

• The 2000–07 Labour Force Surveys (LFS); Stats SA; biannual (March and September).

• The 2008–18 Quarterly Labour Force Surveys (QLFS); Stats SA; quarterly. QFLS earnings

data are released separately in Labour Market Dynamics (LMDSA).

Notably, the major advantage related to the latest release (PALMS version 3.3) is that it exhibits a

labour income variable at individual level that is consistent from 1993 to 2017.

3

This is labelled

‘realearnings’ and reports monthly earnings per capita before taxes and at constant prices as for

December 2015. The full description given in Kerr and Wittenberg (2019b: 16) is as follows:

Monthly REAL earnings variable generated from the earnings amount data (not

bracket information) across all waves where earnings amounts were asked and data

have been released (all waves except OHS 1996 and QFLS waves 2008, 2009 and

2012). This is the earnings variable deflated to 2015 Rands using CPI.

For this reason, PALMS has generated a new strand of academic literature that explores the short-

and long-term dynamics of wage inequality in post-transition South Africa, as well as a vibrant

discussion on the need for higher-quality time-consistent and more frequent microeconomic data.

Although PALMS yields significant improvements in the treatment of labour data in South Africa,

1

According to Devereux (1983), until the 1980s, government censuses ignored the personal incomes of black people,

which had to be calculated as a residual of national accounts. For this and other reasons, this paper refers only to the

post-apartheid period.

2

For a detailed description of primary sources available, see Kerr and Wittenberg (2019a).

3

PALMS version 3.3 includes the 2017 LMDSA data on earnings in quarters 3 and 4.

2

it still preserves a number of incongruities inherited from primary sources. To date, the South

African literature that assesses the sensitivity to economic policy shocks of distributional trends is

almost non-existent precisely because dynamic analyses would suffer from the presence of

methodological shortcomings: spurious shifts among repeated cross-sections are inevitably related

to real changes in the variables of interest. It is nonetheless necessary to use available resources to

identify time trends and changes such that a more granular picture can shed light beyond stylized

facts.

This paper investigates the features inherent in PALMS,

4

thoroughly reviews the literature

addressing issues in South African labour data, and complements earlier studies by constructing a

complete and robust time series of inequality to be used for dynamic economic policy analysis.

The ultimate purpose of the paper is to improve longitudinal analysis on inequality in post-

apartheid South Africa by generating unbiased estimates and accurate standard errors of inequality

coefficients that can be better compared over time with quarterly-frequency data. It lays the ground

for a second paper analysing the impact of monetary policy on labour income inequality in South

Africa.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 offers a selective review of the literature that makes

use of South African income and earnings disaggregated data. Then, in Section 3, the data

underpinning this work is carefully analysed and different methods of adjustment proposed,

compared, and implemented in defiance of data quality issues. In Section 4, I discuss trends of

inequality through distinct measures based on the moments of the earnings distribution. While it

is not feasible to fully address all problems pertaining to primary data collection, the final remarks

discuss what assumptions are needed in order to make defensible comparisons over time. The final

set of complete data on household-level pre-tax wage income at constant prices, along with the

Stata code that was applied to the raw data, is available from the author on request.

2 Labour income in post-apartheid South Africa: a literature review

A number of attempts to quantify inequality dynamics since the advent of democracy in South

Africa explore the quality of surveys and censuses available in the country and eventually comment

on the comparability of relevant variables over time. Cichello et al. (2005) compare 1993 and 1998

earnings in the KwaZulu Natal Income Dynamics Study and reach different results when using

the data as a panel and as a cross-section. Using the cross-sectional data by overlooking specific

workers’ dynamics shows that formal sector workers were better off in 1998. By contrast, the panel

data indicate that workers who were already employed in the formal sector in 1993 experienced a

fall in earnings, while informal workers started at a much lower average earnings point but

experienced a rise due to mobility towards formal employment. Casale et al. (2004) use only the

OHS 1995 and the LFS 2001:2 to analyse the position of women and ethnic groups in the labour

market. In that paper, the authors make no data transformation and assert that ‘these are the years

in which the earnings data are most comparable’ (Casale et al. 2004: 6). Despite data concerns, they

observe that both mean and median earnings declined over the period. Burger and Yu (2007)

compare the OHS and the LFS from 1995 to 2005 by excluding the outliers, the self-employed,

and informal workers. They find that average earnings started to increase and their distribution to

improve after 1998. Following Casale et al. (2004), their figures confirm no improvements in the

relative earnings position of women, non-white population groups, or unskilled and semi-skilled

4

The relatively long span of data necessary to implement this analysis precludes the use of administrative data recently

released by the South African Revenue Service (SARS), which starts in 2011.

3

workers, but they show ‘signs that there has been an decrease in between-group inequality in more

recent years’. Bhorat et al. (2009) utilize the 1995 Income and Expenditure Survey (IES) and the

2005/06 Income and Expenditure Survey, looking at total income, and report increasing inequality

over the period, from an income Gini coefficient of 0.64 in 1995 to 0.72 in 2005. Leibbrandt et al.

(2010) include all forms of labour earnings from three comparable national household survey data

sets: the PSLSD for 1993, the LFS and IES for 2000, and the National Income Dynamics Study

(NIDS) for 2008. With no adjustment, they calculate the income Gini coefficient in South Africa

and report that it rose from 0.66 in 1993 to 0.68 in 2000 and further to 0.70 in 2008. Finn et al.

(2016) use the first four waves of NIDS from 2008 to 2014 and the 1993 PSLSD to investigate

the shape of the association between parental and child earnings across the distribution.

While all previously mentioned authors rely on a few points in time, the most comprehensive study

on long-run trends in labour income inequality in South Africa can be found in the work of

University of Cape Town’s Martin Wittenberg, which indeed serves as the basis for this discussion.

Wittenberg and Pirouz (2013) use PALMSv2 to show the impact of different types of data quality

adjustments (specifically they treat outliers, zero earnings, bracket responses, and missing

observations) on the estimation of the average wage over the period 1994–2011. As already

observed by Casale et al. (2004) and Leibbrandt et al. (2010), Wittenberg and Pirouz (2013) also

evidence how the change in coverage between the OHSs and the successive LFSs generated a gap

in the earnings series at the year 2000. Wittenberg and Pirouz conclude by arguing that it is possible

to identify some real wage growth since 2000 despite the noise generated by these measurement

changes. Wittenberg (2014b) builds on the previous paper to compare PALMS to firm-level data—

namely the Survey of Employment and Earnings (SEE) and the Quarterly Employment Statistics

(QES) surveys. He adds that the top tail of the earnings distribution has received larger gains than

the 75th percentile; that both of them show significant real earnings growth; that the 10th

percentile made real gains relative to the median, therefore experiencing a compression; and that

among the self-employed there is no evidence for systematic shifts in the distribution over the

post-apartheid period. Wittenberg (2017c) effects further adjustments to yield PALMSv2.1 and

calculates wage inequality through the Gini coefficient. He argues that despite some noise in the

estimates, the measurements made after the LFS 2007:1 are noticeably higher than those made

from 2000 to 2006. Finn (2015) calculates the Gini wage inequality in PALMS using the same data-

cleaning procedure suggested by Wittenberg (2014b): in contrast to Leibbrandt et al. (2010), who

calculated overall income inequality, the Gini coefficient of real wages in 2003:1 (0.553) was almost

identical in 2012:1 (0.554). By contrast, using the LFSs, Vermaak (2012) finds no trend that is

robust to alternative coarse data adjustments—particularly the treatment of zero values and the

choice of imputation methods.

3 Working with PALMS

In PALMS, the variable reporting real earnings with no adjustment returns a mean of ZAR8,784

per month and a median of ZAR3,225. The number of observations,

, in the original file

is 963,492; this is higher than in any of the other approaches because every possible earner is

included. However, in the original file more than 5 million real earnings observations are missing,

including all individuals in years 1996, 2008, 2009, and 2018 and the first two quarters of 2019.

Table A1 in the Appendix summarizes the main features of real earnings in PALMSv3.3 before

any adjustment. It can be observed that for each wave the coefficient of variation of the random

variable (standard deviation/mean) is significantly higher than 1: the high variance is due to the

log-normal distribution of real earnings that is not centred on the mean and is positively skewed

with long right tails.