RES E A R C H Open Access

MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a

multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 2:

Epidemiology, clinical presentation,

radiological and laboratory features,

treatment responses, and long-term

outcome

Sven Jarius

1*

, Klemens Ruprecht

2

, Ingo Kleiter

3

, Nadja Borisow

4,5

, Nasrin Asgari

6

, Kalliopi Pitarokoili

3

,

Florence Pache

4,5

,OliverStich

7

, Lena-Alexandra Beume

7

, Martin W. Hümmert

8

, Marius Ringelstein

9

, Corinna Trebst

8

,

Alexander Winkelmann

10

, Alexander Schwarz

1

, Mathias Buttmann

11

, Hanna Zimmermann

2

, Joseph Kuchling

2

,

Diego Franciotta

12

, Marco Capobianco

13

, Eberhard Siebert

14

, Carsten Lukas

15

, Mirjam Korporal-Kuhnke

1

,

Jürgen Haas

1

, Kai Fechner

16

, Alexander U. Brandt

2

, Kathrin Schanda

17

, Orhan Aktas

8

, Friedemann Paul

4,5†

,

Markus Reindl

17†

, and Brigitte Wildemann

1†

; in cooperation with the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS)

Abstract

Background: A subset of patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) has been shown to be

seropositive for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies (MOG-IgG).

Objective: To describe the epidemiological, clinical, radiological, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electrophysiological

features of a large cohort of MOG-IgG-positive patients with optic neuritis (ON) and/or myelitis (n = 50) as well as attack

and long-term treatment outcomes.

Methods: Retrospective multicenter study.

(Continued on next page)

* Correspondence: sven.jarius@med.uni-heidelberg.de

†

Equal contributors

Brigitte Wildemann, Markus Reindl, and Friedemann Paul are equally

contributing senior authors.

1

Molecular Neuroimmunology Group, Department of Neurology, University

of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2016 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribut ion 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Jarius et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2016) 13:280

DOI 10.1186/s12974-016-0718-0

(Continued from previous page)

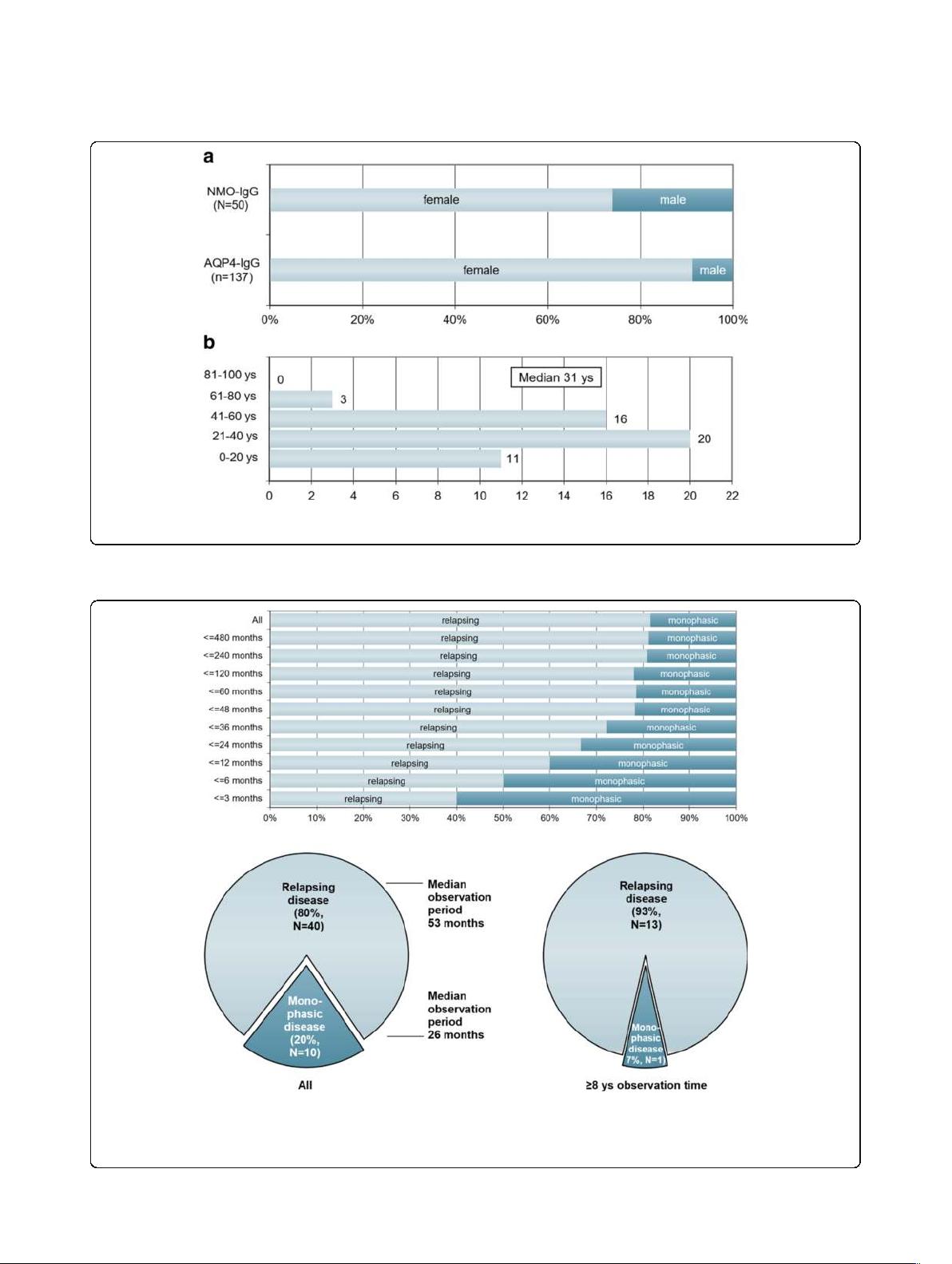

Results: The sex ratio was 1:2.8 (m:f). Median age at onset was 31 years (range 6-70). The disease followed a multiphasic

course in 80% (median time-to-first-relapse5months;annualizedrelapserate0.92)andresultedinsignificantdisabilityin

40% (mean follow-up 75 ± 46.5 months), with severe visual impairment or functional blindness (36%) and markedly

impaired ambulation due to paresis or ataxia (25%) as the most common long-term sequelae. Functional blindness in

one or both eyes was noted during at least one ON attack in around 70%. Perioptic enhancement was present in several

patients. Besides acute tetra-/paraparesis, dysesthesia and pain were common in acute myelitis (70%). Longitudinally

extensive spinal cord lesions were frequent, but short lesions occurred at least once in 44%. Fourty-one percent had a

history of simultaneous ON and myelitis. Clinical or radiological involvement of the brain, brainstem, or cerebellum was

present in 50%; extra-opticospinal symptoms included intractable nausea and vomiting and respiratory insufficiency (fatal

in one). CSF pleocytosis (partly neutrophilic) was present in 70%, oligoclonal bands in only 13%, and blood-CSF-barrier

dysfunction in 32%. Intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) and long-term immunosuppression were often effective;

however, treatment failure leading to rapid accumulation of disability was noted in many patients as well as flare-ups

after steroid withdrawal. Full recovery was achieved by plasma exchange in some cases, including after IVMP failure.

Breakthrough attacks under azathioprine were linked to the drug-specific latency period and a lack of cotreatment with

oral steroids. Methotrexate was effective in 5/6 patients. Interferon-beta was associated with ongoing or increasing

disease activity. Rituximab and ofatumumab were effective in some patients. However, treatment with rituximab was

followed by early relapses in several cases; end-of-dose relapses occurred 9-12 months after the first infusion. Coexisting

autoimmunity was rare (9%). Wingerchuk’s 2006 and 2015 criteria for NMO(SD) and Barkhof and McDonald criteria for

multiple sclerosis (MS) were met by 28%, 32%, 15%, 33%, respectively; MS had been suspected in 36%. Disease onset

or relapses were preceded by infection, vaccination, or pregnancy/delivery in several cases.

Conclusion: Our findings from a predominantly Caucasian cohort strongly argue against the concept of MOG-IgG

denoting a mild and usually monophasic variant of NMOSD. The predominantly relapsing and often severe disease

course and the short median time to second attack support the use of prophylactic long-term treatments in patients with

MOG-IgG-positive ON and/or myelitis.

Keywords: Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies (MOG-IgG), Autoantibodies, Neuromyelitis optica spectrum

disorders (NMOSD), Aquaporin-4 antibodies (AQP4-IgG, NMO-IgG), Optic neuritis, Transverse myelitis, Longitudinally

extensive transverse myelitis, Magnetic resonance imaging, Cerebrospinal fluid, Oligoclonal bands, Electrophysiology,

Evoked potentials, Treatment, Therapy, Methotrexate, Azathioprine, Rituximab, Ofatumumab, Interferon beta, Glatiramer

acetate, Natalizumab, Outcome, Pregnancy, Infections, Vaccination, Multiple sclerosis, Barkhof criteria, McDonald criteria,

Wingerchuk criteria 2006 and 2015, IPND criteria, International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica

spectrum disorders

Background

The term ‘neuromyelitis optica’ (NMO) was coined in

1894 and has since been used to refer to the simultan-

eous or successive occurrence of optic nerve and spinal

cord inflammation [1]. In the majority of cases, the

syndrome is caused by autoantibodies to aquaporin-4,

the most common water channel in the central nervous

system (AQP4-IgG) [2–5]. Howe ver, 10-20% of patients

with NM O are negative for AQP 4-IgG [6–9]. Recent

studies by us and others have demonstrated the presence

of IgG antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycopro-

tein (MOG-IgG) in a subset of patients with NMO as

well as in patients with isolated ON or longitudinally ex-

tensive transverse myelitis (LETM), syndromes that are

often formes frustes of NMO [10–12].

Most studies to date have found MOG-IgG exclusively

in AQP4-IgG-negative patients [11– 17]. Moreover, the

histopathology of brain and spinal cord lesions of MOG-

IgG-positive patients has been shown to differ from that

of AQP4-IgG-posititve patients [18–20]. Finally, evi-

dence from immunological studies suggests a direct

pathogenic role of MOG-IgG both in vitro and in vivo

[10, 21]. Accordingly, MOG-IgG-related NMO is now

considered by many as a disease entity in its own right,

immunopathogenetically distinct from its AQP4-IgG-

positive counterpart. However, the cohorts included in

previous clinical studies were relatively small (median 9

patients in [10–17, 22–24]) and the observation periods

often short (median 24 months in [11–13, 15–17, 23–26]).

Moreover, some previous studies did not, or not predom-

inantly, include Caucasian patients [12, 15, 26], which is

potentially important since genetic factors are thought to

play a role in NMO [27].

In the present study, we syste matically e valuated the

clinical and paraclinical features of a large cohort of 50

almost exclusively Caucasian patients with MOG-IgG-

positive optic neuritis (ON) and/or LETM. We report

on (i) epidemiological features; (ii) clinical presentation

Jarius et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2016) 13:280 Page 2 of 45

at onset; (iii) disease course; (iv) time to second attack;

(v) type and frequency of clinical attacks; (vi) brain, optic

nerve, and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) features; (vii) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings;

(viii) electrophysiological features (VEP, SSEP); (ix) type

and frequency of coexisting autoimmunity; (x) type and

frequency of preceding infections; (xi) association with

neoplasms; (xii) association with pregnancy and delivery;

(xiii) treatment and outcome of acute attacks; (xiv) re-

sponse to long-term treatments; and (xv) the long-term

prognosis. In addition, we evaluated whether and how

many MOG-IgG-positive patients with ON and/or mye-

litis met Wingerchuk’s revised 2006 diagnostic criteria

for NMO [28], the new 2015 international diagnostic

consensus criteria for NMO spectrum disorders

(NMOSD) [29], Barkhof’s MRI criteria for MS, and/or

McDonald’s clinicoradiological criteria for MS.

The present study forms part of a series of articles on

MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders. In part 1, we

investigated the frequency and syndrome specificity of

MOG-IgG among patients with ON and/or LETM,

reported on MOG-IgG titers in the long-term course of

disease, and analyzed the origin of CSF MOG-IgG [30]. In

part 3, we describe in detail the clinical course and presen-

tation of a subgroup of patients with brainstem encephal-

itis and MOG-IgG-associated ON and/or LETM, a so far

under-recognized manifestation of MOG-related auto-

immunity [31]. Part 4 is dedicated to the visual system

in MOG-IgG-positive patient s with ON and reports

findings from optical coherence tomography (OC T ) in

this entity [32].

Methods

Clinical and paraclinical data of 50 MOG-IgG-positive

patients from 12 non-pediatric academic centers were

retrospectively evaluated; eight of the participating cen-

ters are members of the German Neuromyelitis optica

Study Group (NEMOS) [33–37]. MOG-IgG was de-

tected using an in-house cell-based assay (CBA) employ-

ing HEK293A cells transfected with full-length human

MOG as previously described [10] and confirmed by

means of a commercial fixed-cell ba sed assay employing

HEK293 cells transfected with full-le ngth human MOG

(Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) (see part 1 of this art-

icle series for details [30]). The study was approved by the

institutional review boards of the participating centers, and

patients gave written informed consent. Averages are given

as median and range or mean and standard deviation as in-

dicated. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare frequencies

between groups and the Mann-Whitney U test to compare

medians between groups. Due to the exploratory nature of

this study no Bonferroni correction was performed. P

values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Case reports

As reliable ce ll-based assays for t he dete ction of MOG-

IgG have become available only re cently, large and

comprehensive case series illustrating the broad and

heterogeneous spectrum of clinical manifestations, disease

courses, and radiological presentations are lacking so far.

We therefore decided to present, in addition to descriptive

statistical data, detailed reports on all cases evaluated in

order to draw for the first time a more vivid ‘real-life’ pic-

ture of this rare disorder than statistical analyses alone

could provide. Moreover, only detailed case descriptions

allow evaluation of treatment responses and outcomes in

a meaningful way in a retrospective setting. This is im-

portant, since randomized treatment trials in MOG-IgG-

positive ON or myelitis do not exist so far and will not be

performed in the near future due to the rarity of the con-

dition. The reports are to be found in the Appendix of this

paper and in the Case reports section in part 3 of this

article series [31].

Results

Epidemiological findings

Thirty-seven of the 50 MOG-IgG-positive patients were

female, corresponding to a sex ratio of 1:2.8 (m:f) (Fig. 1a).

Median age at onset was 31 years (35.5 years in patients

presenting with isolated ON [N = 32] and 28.5 years in the

remainder [N =18]; p < 0.04) with a broad range of 6 to

70 years. 3 patients were > =60 years of age at onset, and 8

patients were under 18 at first attack (including 4 ≤

12 years) (Fig. 1b). Fourty-nine of the 50 patients (98%)

were of Caucasian and 1 of Asian descent. Symptoms had

started between Jul 1973 and Apr 2016. The mean obser-

vation period since disease onset was 75 ± 46.5 months

(range 1-507 months). In line with the fact that many

MOG-IgG-positive patients develop ON and myelitis only

successively, the mean observation period was longer in

patients with a history both of ON and of myelitis at last

follow-up (88.6 months; N = 22) than in patients with a

history of either ON but no myelitis or myelitis but not

ON (64.6 months; N =28).

Disease course

Fourty of 50 MOG-IgG-positive patients (80%) had a

relapsing disease course. In the remaining 10 cases only

a single attack had occurred at last follow-up. The pro-

portion of patients with a monophasic course declined

with increasing observation time (Fig. 2, upper panel). If

only patients with a very long observation period

(≥8 years) are considered, 93% (13/14) had a recurrent

course (Fig. 2, lower panel). In line with this finding,

the median observati on time was shorter in the ‘mono-

phasic ’ than in the relapsing cases (26 vs. 52.5 months).

The proportion of patients with a relapsing disease

Jarius et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2016) 13:280 Page 3 of 45

Fig. 1 Sex ratio and age distribution. a Sex ratio in MOG-IgG-positive patients with ON and/or LETM compared with AQP4-IgG-positive ON and/or LETM

(the latter data are taken from ref. [34]). b Age distribution at disease onset in 50 MOG-IgG-positive patients with ON and/or myelitis

Fig. 2 Disease course in relation to observation time in 50 MOG-IgG-positive patients with ON and/or myelitis. Upper panel: Note the decrease in

the proportion of monophasic cases with increasing observation time; however, in some patients no relapse has occurred more than 10 years

after the initial attack. Lower panel: Note the shorter observation time in the ‘monophasic’ group (left lower panel) and the lower percentage of

non-relapsing cases among patients with a long observation period ( ≥8 years; right lower panel)

Jarius et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2016) 13:280 Page 4 of 45

course did not differ significantly between female (83.8%

[31/37]) and male (69.2% [9/13]) patients.

Symptoms developed acutely or subacutely in the vast

majority of cases; progressive deterioration of symptoms

was very rare (at least once in 3/46 or 7%) and reported

only in patients with mye litis.

Clinical presentation during acute attacks

Overall, 276 clinically apparent attacks in 50 patients were

documented. 205 attacks clinically affected the optic nerve,

73 the spinal cord, 20 the brainstem, 3 the cerebellum, and

9 the supratentorial brain. 44/50 (88%) patients developed

at least once acute ON, 28/50 (56%) at least once acute

myelitis, 12/50 (24%) at least once a brainstem attack, 2/50

(4%) acute cerebellitis, and 7/50 (14%) acute supratentorial

encephalitis (Fig. 3, upper panel).

At la st follow-up, 26/50 (52%) patients had develope d

at least two different clinical syndromes (i.e., combina-

tions of ON, myelitis, brainstem encephalitis, cerebellitis,

and/or supratentorial encephalitis), either simultaneously

or successively. Of these, 22 (84.6%) had experienced at-

tacks both of ON and of myelitis at last follow-up (cor-

responding to 44% [22/50] of the total cohort). Another

22 (44%) had a history of ON but not of myelitis (recur-

rent in 15 or 68.2%), and 6 (12%) had a history of mye-

litis but not ON (recurrent in 4; LETM in all) at last

follow-up (Fig. 3, lower panel).

Myelitis and ON had occurred simultaneously (with and

without additional brainstem or brain involvement) at least

once in 9/22 (40.9%) patients with a history of both ON

and myelitis at last follow-up (and in 18% or 9/50 in the

total cohort).

Overall, 16/50 (32%) patients presented at least once

with more than one syndrome during a single attack

(more than once in 10/16). While 15 attacks of myelitis

(without ON) in 11 patients were associated with clinical

signs and symptoms of simultaneous brain or brainstem

involvement, only 1 attack of ON (without myelitis)

in 1 patient had this a ssociation. Clinically inapparent

spinal cord, brain, o r brainstem involvement was

detected in further patients by MRI (see Brain MRI

findings below and part 3 of this article series [31]

for details).

Symptoms associated with acute myelitis

Symptoms present at least once during attacks of myeli-

tis included tetraparesis in 8/29 (27.6%) patients, para-

paresis in 14/29 (48.3%), hemiparesis in 2/29 (6. 9%),

and monoparesis in 2/29 (6.9%). Paresis was severe

(BMRC grades ≤2) at lea st o nce in 6/29 (20.7 %)

patients. Attacks included at least once pain and

dysesthesia in 19/28 (67.9%) patients and were purely

sensory in 15/29 (51.7%). Sensory symptoms included

also Lhermitte’s sign. Bladder a nd/or bowel and/or

Fig. 3 Attack history at last follow-up. Upper panel: Frequencies of MOG-IgG-positive patients (N = 50) with a history of clinically manifest acute

optic neuritis (ON), myelitis (MY), brainstem encephalitis (BST), supratentorial encephalitis (BRAIN), and cerebellitis (CBLL) at last follow-up. Lower

panel: Frequencies of MOG-IgG patients with a history of optic neuritis (ON) and myelitis, ON but not myelitis, and myelitis (LETM in all cases) but

not ON, respectively, at last follow-up (n = 50)

Jarius et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2016) 13:280 Page 5 of 45