>

FOR CONFERENCE-RELATED PAPERS, REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR SESSION NUMBER, E.G., AB-02 (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE)

<

1

High-Level Synthesis for FPGAs: From Prototyping to Deployment

Jason Cong

1,2

, Fellow, IEEE, Bin Liu

1,2

,

Stephen Neuendorffer

3

, Member, IEEE, Juanjo Noguera

3

,

Kees Vissers

3

, Member, IEEE and Zhiru Zhang

1

, Member, IEEE

1

AutoESL Design Technologies, Inc.

2

University of California, Los Angeles

3

Xilinx, Inc.

Abstract—Escalating System-on-Chip design complexity is

pushing the design community to raise the level of abstraction

beyond RTL. Despite the unsuccessful adoptions of early

generations of commercial high-level synthesis (HLS) systems, we

believe that the tipping point for transitioning to HLS

methodology is happening now, especially for FPGA designs. The

latest generation of HLS tools has made significant progress in

providing wide language coverage and robust compilation

technology, platform-based modeling, advancement in core HLS

algorithms, and a domain-specific approach. In this paper we use

AutoESL’s AutoPilot HLS tool coupled with domain-specific

system-level implementation platforms developed by Xilinx as an

example to demonstrate the effectiveness of state-of-art C-to-

FPGA synthesis solutions targeting multiple application domains.

Complex industrial designs targeting Xilinx FPGAs are also

presented as case studies, including comparison of HLS solutions

versus optimized manual designs.

Index Terms—Domain-specific design, field-programmable

gate array (FPGA), high-level synthesis (HLS), quality of results

(QoR).

I. I

NTRODUCTION

HE RAPID INCREASE

of complexity in System-on-a-Chip

(SoC) design has encouraged the design community to

seek design abstractions with better productivity than RTL.

Electronic system-level (ESL) design automation has been

widely identified as the next productivity boost for the

semiconductor industry, where HLS plays a central role,

enabling the automatic synthesis of high-level, untimed or

partially timed specifications (such as in C or SystemC) to a

low-level cycle-accurate register-transfer level (RTL)

specifications for efficient implementation in ASICs or

FPGAs. This synthesis can be optimized taking into account

the performance, power, and cost requirements of a particular

system.

Despite the past failure of the early generations of

commercial HLS systems (started in the 1990s), we see a

rapidly growing demand for innovative, high-quality HLS

solutions for the following reasons:

Embedded processors are in almost every SoC: With

the coexistence of micro-processors, DSPs, memories

and custom logic on a single chip, more software

elements are involved in the process of designing a

modern embedded system. An automated HLS flow

allows designers to specify design functionality in high-

level programming languages such as C/C++ for both

embedded software and customized hardware logic on

the SoC. This way, they can quickly experiment with

different hardware/software boundaries and explore

various area/power/performance tradeoffs from a single

common functional specification.

Huge silicon capacity requires a higher level of

abstraction: Design abstraction is one of the most

effective methods for controlling complexity and

improving design productivity. For example, the study

from NEC [90] shows that a 1M-gate design typically

requires about 300K lines of RTL code, which cannot be

easily handled by a human designer. However, the code

density can be easily reduced by 7X to 10X when moved

to high-level specification in C, C++, or SystemC. In this

case, the same 1M-gate design can be described in 30K

to 40K lines of lines of behavioral description, resulting

in a much reduced design complexity.

Behavioral IP reuse improves design productivity: In

addition to the line-count reduction in design

specifications, behavioral synthesis has the added value

of allowing efficient reuse of behavioral IPs. As opposed

to RTL IP which has fixed microarchitecture and

interface protocols, behavioral IP can be retargeted to

different implementation technologies or system

requirements.

Verification drives the acceptance of high-level

specification: Transaction-level modeling (TLM) with

SystemC [107] or similar C/C++ based extensions has

become a very popular approach to system-level

verification [35]. Designers commonly use SystemC

TLMs to describe virtual software/hardware platforms,

which serve three important purposes: early embedded

software development, architectural modeling and

exploration, and functional verification. The wide

availability of SystemC functional models directly drives

the need for SystemC-based HLS solutions, which can

automatically generate RTL code through a series of

formal constructive transformations. This avoids slow

and error-prone manual RTL re-coding, which is the

standard practice in the industry today.

Trend towards extensive use of accelerators and

heterogeneous SoCs: Many SoCs, or even CMPs (chip

multi-processors) move towards inclusion of many

accelerators (or algorithmic blocks), which are built with

custom architectures, largely to reduce power compared

to using multiple programmable processors. According

to ITRS prediction [109], the number of on-chip

accelerators will reach 3000 by 2024. In FPGAs, custom

T

>

FOR CONFERENCE-RELATED PAPERS, REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR SESSION NUMBER, E.G., AB-02 (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE)

<

2

architecture for algorithmic blocks provides higher

performance in a given amount of FPGA resources than

synthesized soft processors. These algorithmic blocks

are particularly appropriate for HLS.

Although these reasons for adopting HLS design

methodology are common to both ASIC and FPGA designers,

we also see additional forces that push the FPGA designers for

faster adoption of HLS tools.

Less pressure for formal verification: The ASIC

manufacturing cost in nanometer IC technologies is well

over $1M [109]. There is tremendous pressure for the

ASIC designers to achieve first tape-out success. Yet

formal verification tools for HLS are not mature, and

simulation coverage can be limited for multi-million gate

SOC designs. This is a significant barrier for HLS

adoption in the ASIC world. However, for FPGA

designs, in-system simulation is possible with much

wider simulation coverage. Design iterations can be

done quickly and inexpensively without huge

manufacturing costs.

Ideal for platform-based synthesis: Modern FPGAs

embed many pre-defined/fabricated IP components, such

as arithmetic function units, embedded memories,

embedded processors, and embedded system buses.

These pre-defined building blocks can be modeled

precisely ahead of time for each FPGA platform and, to

a large extent, confine the design space. As a result, it is

possible for modern HLS tools to apply a platform-based

design methodology [51] and achieve higher quality of

results (QoR).

More pressure for time-to-market: FPGA platforms

are often selected for systems where time-to-market is

critical, in order to avoid long chip design and

manufacturing cycles. Hence, designers may accept

increased performance, power, or cost in order to reduce

design time. As shown in Section IX, modern HLS tools

put this tradeoff in the hands of a designer allowing

significant reduction in design time or, with additional

effort, quality of result comparable to hand-written RTL.

Accelerated or reconfigurable computing calls for

C/C++ based compilation/synthesis to FPGAs: Recent

advances in FPGAs have made reconfigurable

computing platforms feasible to accelerate many high-

performance computing (HPC) applications, such as

image and video processing, financial analytics,

bioinformatics, and scientific computing applications.

Since RTL programming in VHDL or Verilog is

unacceptable to most application software developers, it

is essential to provide a highly automated

compilation/synthesis flow from C/C++ to FPGAs.

As a result, a growing number of FPGA designs are

produced using HLS tools. Some example application

domains include 3G/4G wireless systems [38][81], aerospace

applications [75], image processing [27], lithography

simulation [13], and cosmology data analysis [52]. Xilinx is

also in the process of incorporating HLS solutions in their

Video Development Kit [116] and DSP Develop Kit [97] for

all Xilinx customers.

This paper discusses the reasons behind the recent success

in deploying HLS solutions to the FPGA community. In

Section II we review the evolution of HLS systems and

summarize the key lessons learned. In Sections IV-VIII, using

a state-of-art HLS tool as an example, we discuss some key

reasons for the wider adoption of HLS solutions in the FPGA

design community, including wide language coverage and

robust compilation technology, platform-based modeling,

advancement in core HLS algorithms, improvements on

simulation and verification flow, and the availability of

domain-specific design templates. Then, in Section IX, we

present the HLS results on several real-life industrial designs

and compare with manual RTL implementations. Finally, in

Section X, we conclude the paper with discussions of future

challenges and opportunities.

II. E

VOLUTION OF HIGH

-

LEVEL SYNTHESIS FOR

FPGA

In this section we briefly review the evolution of high-level

synthesis by looking at representative tools. Compilers for

high-level languages have been successful in practice since the

1950s. The idea of automatically generating circuit

implementations from high-level behavioral specifications

arises naturally with the increasing design complexity of

integrated circuits. Early efforts (in the 1980s and early 1990s)

on high-level synthesis were mostly research projects, where

multiple prototype tools were developed to call attention to the

methodology and to experiment with various algorithms. Most

of those tools, however, made rather simplistic assumptions

about the target platform and were not widely used. Early

commercialization efforts in the 1990s and early 2000s

attracted considerable interest among designers, but also failed

to gain wide adoption, due in part to usability issues and poor

quality of results. More recent efforts in high-level synthesis

have improved usability by increasing input language

coverage and platform integration, as well as improving

quality of results.

A. Early Efforts

Since the history of HLS is considerably longer than that of

FPGAs, most early HLS tools targeted ASIC designs. A

pioneering high-level synthesis tool, CMU-DA, was built by

researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in the 1970s

[29][71]. In this tool the design is specified at behavior level

using the ISPS (Instruction Set Processor Specification)

language [4]. It is then translated into an intermediate data-

flow representation called the Value Trace [79] before

producing RTL. Many common code-transformation

techniques in software compilers, including dead-code

elimination, constant propagation, redundant sub-expression

elimination, code motion, and common sub-expression

extraction could be performed. The synthesis engine also

included many steps familiar in hardware synthesis, such as

datapath allocation, module selection, and controller

generation. CMU-DA also supported hierarchical design and

included a simulator of the original ISPS language. Although

many of the methods used were very preliminary, the

>

FOR CONFERENCE-RELATED PAPERS, REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR SESSION NUMBER, E.G., AB-02 (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE)

<

3

innovative flow and the design of toolsets in CMU-DA

quickly generated considerable research interest.

In the subsequent years in the 1980s and early 1990s, a

number of similar high-level synthesis tools were built, mostly

for research. Examples of academic efforts include the ADAM

system developed at the University of Southern California

[37][46], HAL developed at Bell-Northern Research [72],

MIMOLA developed at University of Kiel, Germany [62], the

Hercules/Hebe high-level synthesis system (part of the

Olympus system) developed at Stanford University [24][25]

[55], the Hyper/Hyper-LP system developed at University of

California, Berkeley [10][77]. Industry efforts include

Cathedral/Cathedral-II and their successors developed at

IMEC [26], the IBM Yorktown Silicon Compiler [11] and the

GM BSSC system [92], among many others. Like CMU-DA,

these tools typically decompose the synthesis task into a few

steps, including code transformation, module selection,

operation scheduling, datapath allocation, and controller

generation. Many fundamental algorithms addressing these

individual problems were also developed. For example, the list

scheduling algorithm and its variants are widely used to solve

scheduling problems with resource constraints [70]; the force-

directed scheduling algorithm developed in HAL [73] is able

to optimize resource requirements under a performance

constraint; the path-based scheduling algorithm in the

Yorktown Silicon Compiler is useful to optimize performance

with conditional branches [12]. The Sehwa tool in ADAM is

able to generate pipelined implementations and explore the

design space by generating multiple solutions [69]. The

relative scheduling technique developed in Hebe is an elegant

way to handle operations with unbounded delay [56]. Conflict-

graph coloring techniques were developed and used in several

systems to share resources in the datapath [57][72].

These early high-level tools often used custom languages

for design specification. Besides the ISPS language used in

CMD-DA, a few other languages were notable. HardwareC is

a language designed for use in the Hercules system [54].

Based on the popular C programming language, it supports

both procedural and declarative semantics and has built-in

mechanisms to support design constraints and interface

specifications. This is one of the earliest C-based hardware

synthesis languages for high-level synthesis and is interesting

to compare with similar languages later. The Silage language

used in Cathedral/Cathedral-II was specifically designed for

the synthesis of digital signal processing hardware [26]. It has

built-in support for customized data types, and allows easy

transformations [77][10]. The Silage language, along with the

Cathedral-II tool, represented an early domain-specific

approach in high-level synthesis.

These early research projects helped to create a basis for

algorithmic synthesis with many innovations, and some were

even used to produce real chips. However, these efforts did

not lead to wide adoption among designers. A major reason is

that the methodology of using RTL synthesis was not yet

widely accepted at that time and RTL synthesis tools were not

yet mature. Thus, high-level synthesis, built on top of RTL

synthesis, did not have a sound foundation in practice. In

addition, simplistic assumptions were often made in these

early systems—many of them were “technology independent”

(such as Olympus), and inevitably led to suboptimal results.

With improvements in RTL synthesis tools and the wide

adoption of RTL-based design flows in the 1990s, industrial

deployment of high-level synthesis tools became more

practical. Proprietary tools were built in major semiconductor

design houses including IBM [5], Motorola [58], Philips [61],

and Simens [6]. Major EDA vendors also began to provide

commercial high-level synthesis tools. In 1995, Synopsys

announced Behavioral Compiler [88], which generates RTL

implementations from behavioral HDL code and connects to

downstream tools. Similar tools include Monet from Mentor

Graphics [33] and Visual Architect from Cadence [43]. These

tools received wide attention, but failed to widely replace RTL

design. One reason is due to the use of behavioral HDLs as the

input language, which

is not popular among

algorithm and

system designers.

B. Recent efforts

Since 2000, a new generation of high-level synthesis tools

has been developed in both academia and industry. Unlike

many predecessors, most of these tools focus on using C/C++

or C-like languages to capture design intent. This makes the

tools much more accessible to algorithm and system designers

compared to previous tools that only accept HDL languages. It

also enables hardware and software to be built using a

common model, facilitating software/hardware co-design and

co-verification. The use of C-based languages also makes it

easy to leverage the newest technologies in software compilers

for parallelization and optimization in the synthesis tools.

In fact, there has been an ongoing debate on whether C-

based languages are proper choices for HLS [31][78]. Despite

the many advantages of using C-based languages, opponents

often criticize C/C++ as languages only suitable for describing

sequential software that runs on microprocessors. Specifically,

the deficiencies of C/C++ include the following:

(i) Standard C/C++ lack built-in constructs to explicitly

specify bit accuracy, timing, concurrency, synchronization,

hierarchy, etc., which are critical to hardware design.

(ii) C and C++ have complex language constructs, such as

pointers, dynamic memory management, recursion,

polymorphism, etc., which do have efficient hardware

counterparts and lead to difficulty in synthesis.

To address these deficiencies, modern C-based HLS tools

have introduced additional language extensions and

restrictions to make C inputs more amenable to hardware

synthesis. Common approaches include both restriction to a

synthesizable subset that discourages or disallows the use of

dynamic constructs (as required by most tools) and

introduction of hardware-oriented language extensions

(HardwareC [54], SpecC [34], Handel-C [95]), libraries

(SystemC [107]), and compiler directives to specify

concurrency, timing, and other constraints. For example,

Handel-C allows the user to specify clock boundaries

explicitly in the source code. Clock edges and events can also

be explicitly specified in SpecC and SystemC. Pragmas and

>

FOR CONFERENCE-RELATED PAPERS, REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR SESSION NUMBER, E.G., AB-02 (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE)

<

4

directives along with a subset of ANSI C/C++ are used in

many commercial tools. An advantage of this approach is that

the input program can be compiled using standard C/C++

compilers without change, so that such a program or a module

of it can be easily moved between software and hardware and

co-simulation of hardware and software can be performed

without code rewriting. At present, most commercial HLS

tools use some form of C-based design entry, although tools

using other input languages (e.g., BlueSpec [102], Esterel [30],

Matlab [42], etc.) also exist.

Another notable difference between the new generation of

high-level synthesis tools and their predecessors is that many

tools are built targeting implementation on FPGA. FPGAs

have continually improved in capacity and speed in recent

years, and their programmability makes them an attractive

platform for many applications in signal processing,

communication, and high-performance computing. There has

been a strong desire to make FPGA programming easier, and

many high-level synthesis tools are designed to specifically

target FPGAs, including ASC [64], CASH [9], C2H from

Altera [98], DIME-C from Nallatech [112], GAUT [22],

Handel-C compiler (now part of Mentor Graphics DK Design

Suite) [95], Impulse C [74], ROCCC [87][39], SPARK

[41][40], Streams-C compiler [36], and Trident [82][83], .

ASIC tools also commonly provide support for targeting an

FPGA tool flow in order to enable system emulation.

Among these high-level synthesis tools, many are designed

to focus on a specific application domain. For example, the

Trident compiler, developed at Los Alamos National Lab, is

an open-source tool focusing on the implementation of

floating-point scientific computing applications on FPGA.

Many tools, including GAUT, Streams-C, ROCCC, ASC, and

Impulse C, target streaming DSP applications. Following the

tradition of Cathedral, these tools implement architectures

consisting of a number of modules connected using FIFO

channels. Such architectures can be integrated either as a

standalone DSP pipeline, or integrated to accelerate code

running on a processor (as in ROCCC).

As of 2010, major commercial C-based high-level synthesis

tools include AutoESL’s AutoPilot [94] (originated from

UCLA xPilot project [17]), Cadence’s C-to-Silicon Compiler

[3][103], Forte’s Cynthesizer [65], Mentor’s Catapult C [7],

NEC’s Cyber Workbench [89][91], and Synopsys Synphony C

[115] (formerly Synfora’s PICO Express, originated from a

long range research effort in HP Labs [49]).

C. Lessons Learned

Despite extensive development efforts, most commercial

HLS efforts have failed. We believe that past failures are due

to one or several of the following reasons:

Lack of comprehensive design language support: The

first generation of the HLS synthesis tools could not

synthesize high-level programming languages. Instead,

untimed or partially timed behavioral HDL was used.

Such design entry marginally raised the abstraction

level, while imposing a steep learning curve on both

software and hardware developers.

Although early C-based HLS technologies have

considerably improved the ease of use and the level of

design abstraction, many C-based tools still have glaring

deficiencies. For instance, C and C++ lack the necessary

constructs and semantics to represent hardware attributes

such as design hierarchy, timing, synchronization, and

explicit concurrency. SystemC, on the other hand, is

ideal for system-level specification with

software/hardware co-design. However, it is foreign to

algorithmic designers and has slow simulation speed

compared to pure ANSI C/C++ descriptions.

Unfortunately, most early HLS solutions commit to only

one of these input languages, restricting their usage to

niche application domains.

Lack of reusable and portable design specification:

Many HLS tools have required users to embed detailed

timing and interface information as well as the synthesis

constraints into the source code. As a result, the

functional specification became highly tool-dependent,

target-dependent, and/or implementation-platform

dependent. Therefore, it could not be easily ported to

alternative implementation targets.

7arrow focus on datapath synthesis: Many HLS tools

focus primarily on datapath synthesis, while leaving

other important aspects unattended, such as interfaces to

other hardware/software modules and platform

integration. Solving the system integration problem then

becomes a critical design bottleneck, limiting the value

in moving to a higher-level design abstraction for IP in a

design.

Lack of satisfactory quality of results (QoR): When

early generations of HLS tools were introduced in the

mid-1990s to early 2000s, the EDA industry was still

struggling with timing closure between logic and

physical designs. There was no dependable RTL to

GDSII foundation to support HLS, which made it

difficult to consistently measure, track, and enhance

HLS results. Highly automated RTL to GDSII solutions

only became available in late 2000s (e.g., provided by

the IC Compiler from Synopsys [114] or the

BlastFusion/Talus from Magma [111]). Moreover, many

HLS tools are weak in optimizing real-life design

metrics. For example, the commonly used algorithms

mainly focus on reducing functional unit count and

latency, which do not necessarily correlate to actual

silicon area, power, and performance. As a result, the

final implementation often fails to meet timing/power

requirements. Another major factor limiting quality of

result was the limited capability of HLS tools to exploit

performance-optimized and power-efficient IP blocks on

a specific platform, such as the versatile DSP blocks and

on-chip memories on modern FPGA platforms. Without

the ability to match the QoR achievable with an RTL

design flow, most designers were unwilling to explore

potential gains in design productivity.

Lack of a compelling reason/event to adopt a new

design methodology: The first-generation HLS tools

>

FOR CONFERENCE-RELATED PAPERS, REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR SESSION NUMBER, E.G., AB-02 (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE)

<

5

were clearly ahead of their time, as the design

complexity was still manageable at the register transfer

level in late 1990s. Even as the second-generation of

HLS tools showed interesting capabilities to raise the

level of design abstraction, most designers were

reluctant to take the risk of moving away from the

familiar RTL design methodology to embrace a new

unproven one, despite its potential large benefits. Like

any major transition in the EDA industry, designers

needed a compelling reason or event to push them over

the “tipping point,” i.e., to adopt the HLS design

methodology.

Another important lesson learned is that tradeoffs must be

made in the design of the tool. Although a designer might

wish for a tool that takes any input program and generates the

“best” hardware architecture, this goal is not generally

practical for HLS to achieve. Whereas compilers for

processors tend to focus on local optimizations with the sole

goal of increasing performance, HLS tools must automatically

balance performance and implementation cost using global

optimizations. However, it is critical that these optimizations

be carefully implemented using scalable and predictable

algorithms, keeping tool runtimes acceptable for large

programs and the results understandable by designers.

Moreover, in the inevitable case that the automatic

optimizations are insufficient, there must be a clear path for a

designer to identify further optimization opportunities and

execute them by rewriting the original source code.

Hence, it is important to focus on several design goals for a

high-level synthesis tool:

1. Capture designs at a bit-accurate, algorithmic level in

C code. The code should be readable by algorithm

specialists.

2. Effectively generate efficient parallel architectures

with minimal modification of the C code, for

parallelizable algorithms.

3. Allow an optimization-oriented design process, where

a designer can improve the performance of the

resulting implementation by successive code

modification and refactoring.

4. Generate implementations that are competitive with

synthesizable RTL designs after automatic and manual

optimization.

We believe that the tipping point for transitioning to HLS

methodology is happening now, given the reasons discussed in

Section I and the conclusions by others [14][84]. Moreover,

we are pleased to see that the latest generation of HLS tools

has made significant progress in providing wide language

coverage and robust compilation technology, platform-based

modeling, and advanced core HLS algorithms. We shall

discuss these advancements in more detail in the next few

sections.

III. C

ASE

S

TUDY OF

S

TATE

-

OF

-

ART OF HIGH

-

LEVEL

SYNTHESIS FOR

FPGA

S

AutoPilot is one of the most recent HLS tools, and is

representative of the capabilities of the state-of-art commercial

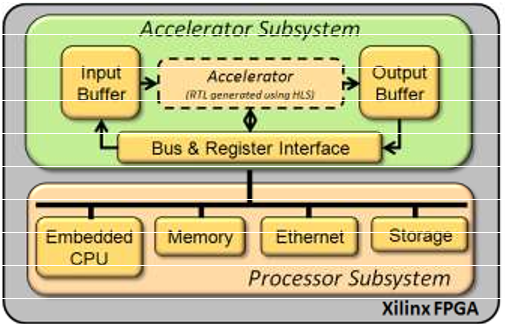

HLS tools available today. Figure 1 shows the AutoESL

AutoPilot development flow targeting Xilinx FPGAs.

AutoPilot accepts synthesizable ANSI C, C++, and OSCI

SystemC (based on the synthesizable subset of the IEEE-1666

standard [113]) as input and performs advanced platform-

based code transformations and synthesis optimizations to

generate optimized synthesizable RTL.

AutoPilot outputs RTL in Verilog, VHDL or cycle-accurate

SystemC for simulation and verification. To enable automatic

co-simulation, AutoPilot creates test bench wrappers and

transactors in SystemC so that designers can leverage the

original test framework in C/C++/SystemC to verify the

correctness of the RTL output. These SystemC wrappers

connect high-level interfacing objects in the behavioral test

bench with pin-level signals in RTL. AutoPilot also generates

appropriate simulation scripts for use with 3

rd

-party RTL

simulators. Thus designers can easily use their existing

simulation environment to verify the generated RTL.

AutoPilot

Synthesis

AutoPilot

Simulation

AutoPilot

Module

Generation

High-level

Spec (C,

C++,

SystemC)

Design

Test Bench

RTL

(SystemC,

VHDL,

Verilog)

Design

Wrapper

Synthesis

Directives

Simulation

Scripts

Implementation

Scripts

RTL/Netlist

Xilinx ISE

EDK

Xilinx

CoreGen

RTL

Simulator

FPGA Platform Libs

Bitstream

Figure 1. AutoESL and Xilinx C-to-FPGA design flow.

In addition to generating RTL, AutoPilot also creates

synthesis reports that estimate FPGA resource utilization, as

well as the timing, latency and throughput of the synthesized

design. The reports include a breakdown of performance and

area metrics by individual modules, functions and loops in the

source code. This allows users to quickly identify specific

areas for QoR improvement and then adjust synthesis

directives or refine the source design accordingly.

Finally, the generated HDL files and design constraints feed

into the Xilinx RTL tools for implementation. The Xilinx ISE

tool chain (such as CoreGen, XST, PAR, etc.) and Embedded

Development Kit (EDK) are used to transform that RTL

implementation into a complete FPGA implementation in the

form of a bitstream for programming the target FPGA

platform.